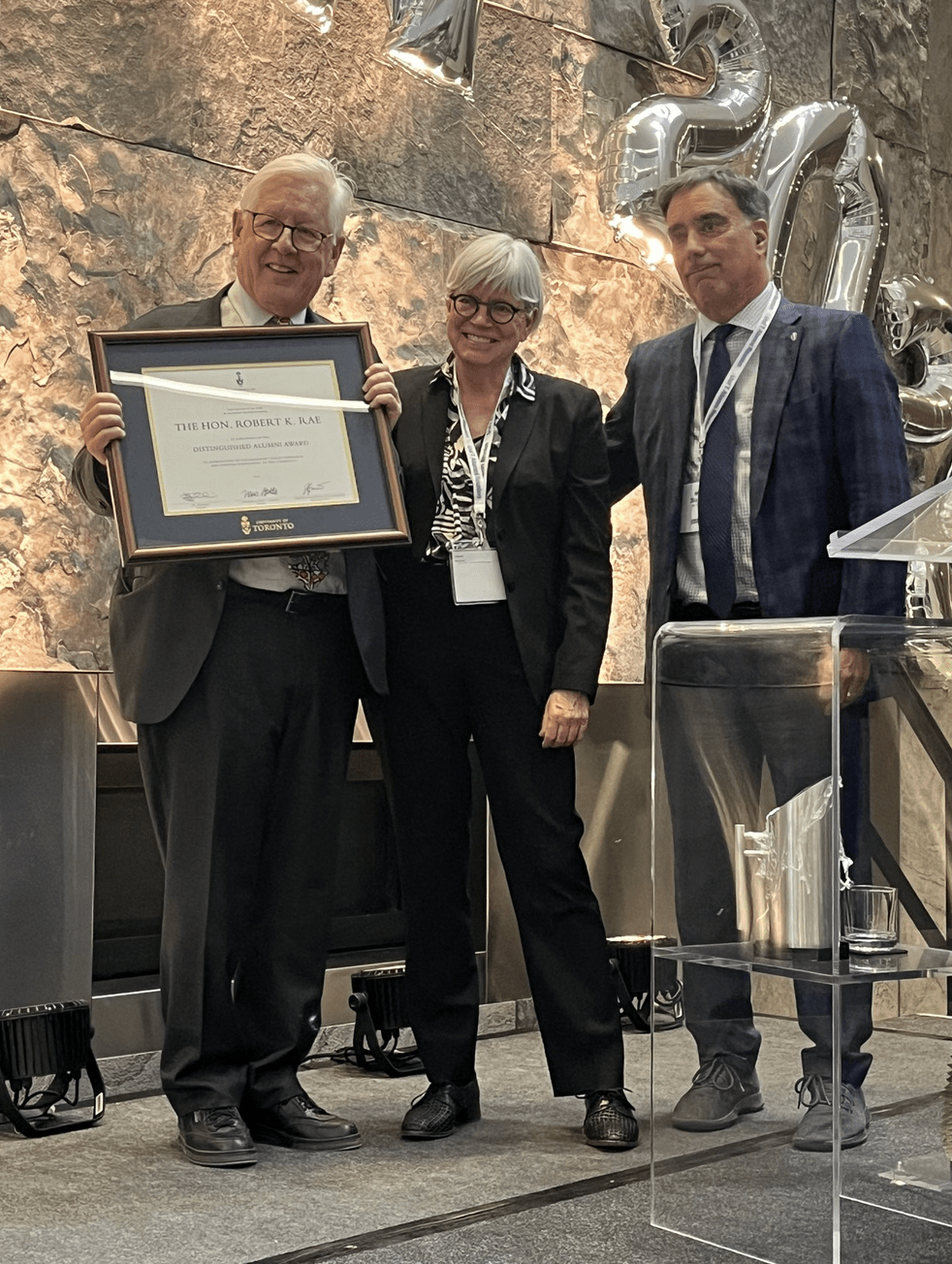

Despair is Not an Option: Ambassador Bob Rae on Accepting the U of T Law Faculty Distinguished Alumni Award

On May 29, 2025, United Nations Ambassador Bob Rae was awared the Distinguished Alumni Award from the University of Toronto Faculty of Law. The following is the text of his acceptance remarks.

I am very grateful to receive this distinguished alumni award from the University of Toronto Faculty of Law this evening. I am also delighted to be joined by family and friends.

My progress in life, in the law, politics, public service and teaching is living proof of Kant’s saying that “from the crooked stick of humanity nothing straight was ever made.” In addition to my work as a lawyer, I have practiced my advocacy in the court of public opinion, whose decisions can be swift and unforgiving, and in parliaments provincial, national, and now international, where the length of the speech is often in inverse proportion to the impact on the listener.

But this law school did much more for me than help an often-confused mind and even troubled soul accept the discipline and rigour of legal reasoning and principles. I have made friends for life here (some, sadly, no longer with us), developed my advocacy skills before legal tribunals, enjoyed conversations late into the night on all topics and appreciated the ongoing goodwill that has allowed me to return to the school as a teacher and even a master of ceremonies at our 75th anniversary. Who knows, I may try and return again!

In the world we are living in today, the rule of law has never been more important. The French philosopher Pascal put it this way, “Justice without force is powerless; but force without justice is tyranny.” So, the issues and problems that surround us are hardly new – the paradox Pascal describes is universal and eternal. But that does not mean we can shrug our shoulders and pretend there is nothing we can do.

On January 6, 1941, Franklin Roosevelt delivered his State of the Union Address. He knew that the world around him was collapsing in the face of brutal, authoritarian attacks, and Britain by January 1941 stood alone in Europe. But he also knew that leaders needed followers, and that his task was to persuade the American public that the United States could not abandon those – like Canadians – who had already made the decision to fight against fascism and for freedom and democracy.

The January 6, 1941, speech is often referred to as the “Four Freedoms” speech. In it, Roosevelt talked of the central importance of

- Freedom of speech

- Freedom of worship

- Freedom from fear

- Freedom from want

These were not just freedoms for Americans, they were freedoms of all people. It was a bold vision. It put him at odds with the isolationists of his day, just as the idea of universal principles puts it at odds with the narrow nationalisms of our time.

It was also an idea that was rejected by many authoritarians in the world who believed then, as they do now, that human rights are not universal, but are rather culturally determined. This ignores the fact that in all religions, there are concepts of mutual obligation, dignity of the individual, and the importance of respecting the idea of laws that bind and apply to all. Nowhere do we find the notion that tyranny or cruelty are to be celebrated as universally good.

Six months later, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill met off the coast of Newfoundland. The result was the Atlantic Charter, which is, in reality, the basis of both the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was proclaimed in 1948.

Those principles were:

- no territorial changes made against the wishes of the people

- Self-government as a defining principle of the new order, replacing the colonialism of the past

- Freer trade and freedom of the seas

- More co-operation to improve the global economy

- Disarmament of aggressor nations and rejection of force as the basis to settle disputes

Our modern international legal architecture would not have existed without both Roosevelt’s vision and American leadership. The challenges we face today require a renewal of that commitment from all of us.

The global challenges we face — conflict, aggression, crimes against humanity, lies, disinformation, climate change, deep poverty and growing inequality, the ongoing presence and threat of pandemics and other health challenges — cannot be met by the nation state alone. While action at the local and national level can achieve success in the effort to combat these global realities, they are insufficient, and will only work if accompanied by joined up action. Global problems that cross borders need global solutions.

The main flaw in the laws and treaties that we have is that their enforcement is weak and uneven. The principal enemy of enforcement is the insistence by many countries that somehow they are different or exceptional, that the rules do not apply to them, that their sovereignty is more important than the greater good of humanity. This is at the heart of our current challenge.

It is important to remember that the principle that Mr. Justice Robert Jackson stated in his opening address to the Nuremberg Tribunal in 1945 remains true: the law is not only concerned with local and commercial issue. Great crimes of global impact must be met with the full force of the law.

Canada’s commitment to the rule of law is based on both our values and our self-interest. Together with a great many other countries, we have learned the hard way that collective security is essential for our individual freedoms, and that we have to rely on mutually agreed and effectively enforced rules to advance our interests. There is no other path for us. For example, in trade disputes between Canada and the United States, we require and need effective tools of mediation and arbitration to ensure that might does not always make right. And in agreeing to an effective regime under NAFTA and its successors, the United States preserves its interests as well.

Everyone is heartened that appeals to the rule of law in the United States lead to court and trade tribunal decisions emphatically on the side of the law. But when executive power anywhere in the world is invoked to justify breaking those rules we are heading right back to the very world of chaos, protectionism, nationalism and indeed authoritarianism we were supposed to have put behind us when we signed the UN Charter in San Francisco some 80 years ago.

It seems bizarre to have to remind ourselves and others that the basis of the UN Charter is that it is intended to protect the integrity of nation states, and that to even threaten the integrity of other states is against the law.

Canadians have a special sense of pride that when we celebrated the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, we honoured the memory of a Canadian legal scholar, John Humphrey, who as an international civil servant at the United Nations in the 1940s ‘held the pen’ in the drafting of this document. The ethical foundation of that document is the same as that expressed by Franklin Roosevelt in 1941, that human rights are not a product of one legal or cultural tradition or another, but can be found in what it means to share both our common humanity and the reality that morality itself is based on the principle that freedom and dignity require mutual respect and the recognition that the pursuit of selfish ego on its own leads not to civilization but to its destruction.

I was proud when the first speech Justin Trudeau gave at the United Nations as Prime Minister was about indigenous rights. Indigenous people in Canada had been important leaders in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People, but it took us a decade to ratify it. He spoke about our shared experience of colonialism, that we had much to understand and overcome in our history, and that the road to equality passes through Canada as much as it does through all countries. The acceptance of international law and standards has the effect of lifting us all up, and holds governments accountable. No matter how mighty or sovereign we might be, the law applies to all of us.

The means we use to communicate and share information are being flooded with lies and hate at a pace and level that is completely unprecedented. Conspiracy theories, antisemitism, misogyny, phobias and hatreds of all kinds are spreading at the speed of sound, and being amplified and magnified in ways that Goebbels could only dream of. The ugliness of political debate has never been greater, and the cowards of hate hide behind pseudonyms as they enter the brawl of social media.

Armed with guns as well as megaphones, the perpetrators of unrest and chaos take many different forms in many different societies.

But despair in the face of all this is not an option. The only path that will work is to commit ourselves to reason, law, civility, and, yes, enforcement. The remedy for disorder is order. Not an order based on repression or dictatorship, but on the rule of law itself, recognizing that the common good of humanity demands no less.

This is not a pipe dream, because it is based on the simple premise that our self-interest and our values align at this “sweet spot”, this place where our freedoms and our survival require us to dedicate ourselves to the rule of law not just in our own cities and towns and countries, but in a world that cannot be alien or foreign to us because it touches us all so closely, and above all because it reflects our common humanity.

Bob Rae is Canada’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations.