A Defining Moment for the Global Order

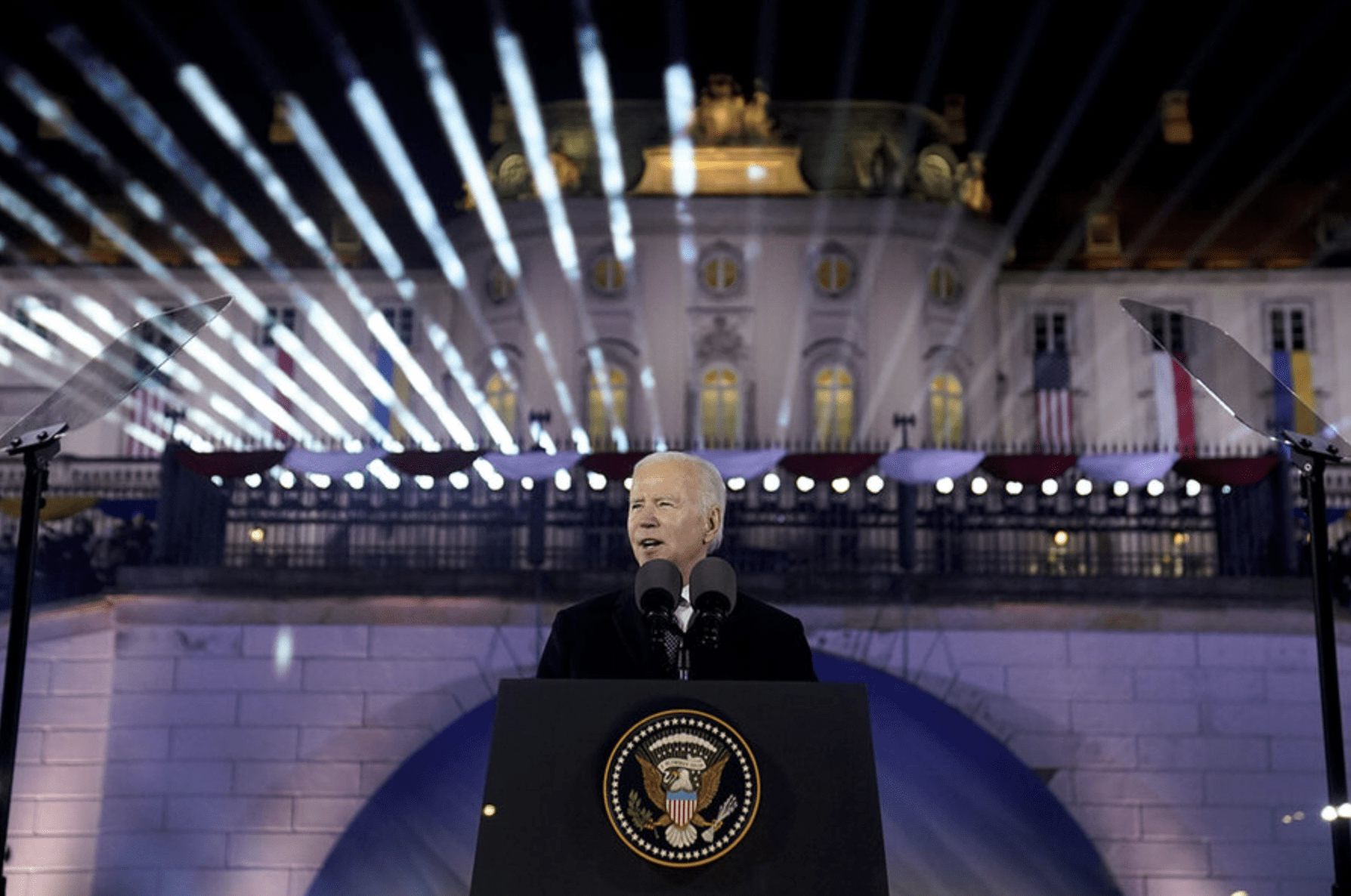

President Joe Biden speaks in Warsaw on February 21, 2023/AP

President Joe Biden speaks in Warsaw on February 21, 2023/AP

Kerry Buck

February 22, 2023

For me, as for the people of Ukraine, Russia’s war on Ukraine is much more than one year old. It began nine years ago, when Russia illegally annexed the Crimean Peninsula.

In late February 2014, it was midday in Ottawa when I got a call from the prime minister’s foreign policy advisor at Privy Council Office. She told me that alarming intelligence reports were rolling in of soldiers appearing in the Crimean Peninsula of Ukraine, bearing Russian weapons but without national insignia. The presence of Russian military in Crimea was not surprising – their Black Sea Fleet had been in Crimea since the early 1800s. What was alarming was the apparent purpose – the “unidentified” soldiers had appeared outside Crimean airports and key buildings in the Crimean capital, including the legislature. On March 18th, Vladimir Putin presided over a ceremony at the Kremlin illegally declaring Crimea Russian territory.

At the time, I was Canadian political director, a diplomatic position in foreign ministries responsible for the major geopolitical issues of the day. Basically, anything big and bad and international gets handed to political directors, so I had a front row seat to the reaction of the G7 and NATO allies to Russia’s violation of Ukrainian borders. In hindsight, the reaction in 2014 – suspension of Russia from the G8/G7 and imposition of broad sanctions – was inadequate because it failed to deter the Russian leader from launching a full-scale invasion of Ukraine eight years later. But at the time, the international condemnation of Russia by G7 and NATO allies was much stronger than I had expected.

We need to remember that, prior to 2014, most of Canada’s close allies were still hopeful post-Soviet Russia could be brought closer to the West. Russia had worked with NATO on a number of issues, including facilitating transit of NATO assets into Afghanistan. If you walked into the NATO Headquarters cafeteria, you would see Russian military personnel sitting with Allied soldiers. The NATO-Russia Council (NRC) met frequently and there was a network of political and military sub-committees under the NRC working on Russia-NATO cooperation and transparency. Putin had even said years earlier in an interview with the BBC that “Russia is part of Europe. I cannot imagine my own culture in isolation from Europe […]so it is hard for me to visualise NATO as an enemy. […] I would not even rule out [the] possibility of [Russia joining NATO].”

And yet, here we are today, 12 months after a brutal Russian attempt to invade all of Ukraine, with millions of Ukrainians displaced, tens of thousands of casualties and almost 8,000 civilians murdered. Ukrainian critical infrastructure and cultural heritage have been destroyed. Countless war crimes have been committed and Russia is under the heaviest sanctions imposed on any country since the Second World War. The fighting continues and a new offensive is being launched in the east of Ukraine in what promises to be a grinding ground war along a 600-kilometre front. Most are predicting that this conflict will last a long time.

Some, myself included, see the Russian invasion of Ukraine as a hinge of history, a development so significant that it rearranges the building blocks of the international order. In some ways, the past year has been a test of the international community to see if it can respond with sufficient unity and purpose to protect the values the post-war order was built on. That test is ongoing but so far, I would give the international community — and NATO as an integral part of that community — a passing grade for its initial response.

I hesitate to do so because any self-congratulation by the West for its response to Russia might be misconstrued as disrespectful to the extraordinary courage shown by the Ukrainian leadership, military and citizens, to say nothing of the terrible price paid by Ukrainian civilians. One year ago today, the world was bracing for the fall of Kyiv. The military successes of the Ukrainian armed forces since then have been both unexpected and inspiring, humbling one of the world’s largest militaries. That, coupled with President Zelensky’s visionary leadership, has galvanized western support.

My hesitation in giving the international community a passing grade also flows from the fact that it is premature. As the war grinds on, and further damage is inflicted on Ukraine by Moscow, supplied as it is with many more soldiers and much more weaponry than Ukraine, there is a real risk that Western unity on Ukraine will start to falter, or that complacency will take over. Putin is likely banking on it.

As Biden said Tuesday in Warsaw, the world is at an inflection point, with authoritarian governments staging a challenge against global democracy unprecedented since 1945, and ‘decisions made over the next five years’ that will shaping the world ‘for decades’.

That is why President Biden’s speech in Warsaw on Tuesday focused on the West’s resolve: “[Putin] doubts our staying power. He doubts our continued support to Ukraine. He doubts whether NATO can remain unified. But there should be no doubt our support for Ukraine will not waver.”

So far, Biden is correct. The West’s resolve and NATO unity was impressive at the start of the Russian war a year ago and has grown even stronger over the past year, with an early shift by Allies to provide lethal weaponry, from air defence to tanks, imposition of stringent sanctions, cross-regional condemnation of Russia at the UN General Assembly, and NATO building up its support to Ukraine and its deterrence posture on NATO’s eastern flank. As Jens Stoltenberg, the Secretary General of NATO has said repeatedly, NATO now is stronger than it has ever been.

So far, so good. But will the West’s passing grade hold? I see several areas where fault lines could emerge in the medium term. As Biden said Tuesday in Warsaw, the world is at an inflection point, with authoritarian governments staging a challenge against global democracy unprecedented since 1945, and “decisions made over the next five years” that will shape the world “for decades.” Those decisions will be about much more than what support we provide to Ukraine.

One of the existential questions the West will need to address is how to deal with a post-war Russia. At some point, the war will end. I won’t dare to predict how or when. If Russia is completely defeated by Ukraine, and loses even Crimea, it is hard to see how Putin can remain in power. But after years of defenestrations, mysterious suicides, poisonings and lengthy jail sentences, there are no rivals or heirs apparent waiting in the wings behind Putin who could assume power in any stable fashion. A dangerous vacuum could emerge.

Alternatively, any scenario less than full Ukrainian victory could result in Putin staying in power. And as the world learned after 2014, Putin will try again. His imperial aims are the one predictable thing about Putin’s leadership. Whatever scenario emerges from the war, Russia will likely continue to have an ongoing destabilizing political and economic impact in Europe. And the West will have to be ready with unified strategies to deal with a wounded Russia after the war.

The Russian war has also had an impact on the effectiveness of multilateral institutions. President Zelensky has, quite rightly, been very critical of the UN Security Council, asking “where is the security?” The fault lines built into the structure of the UN Security Council from its inception — notably the veto assigned the five permanent members, including Russia and China — have been laid bare. Some former colleagues have even said that the UN Security Council is dead. But that doesn’t mean the UN is dead — imagine the humanitarian response to the war in Ukraine without the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or the World Food Programme (WFP). It would be much slower and less effective. Imagine the prosecution of war crimes and crimes against humanity after the war without the International Criminal Court (ICC) or the commission of inquiry created by the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC). While the Security Council might be reaching a “League of Nations” moment, where its inability to provide collective security has undermined its credibility and could lead to its demise, the UN as a whole is a necessary and useful part of the international response to the war in Ukraine.

NATO has fared much better, able to take strong and unified political positions and coordinate the delivery of vital weapons and equipment to Ukraine. But NATO unity is not a given — it wasn’t that long ago that President Emmanuel Macron declared NATO “brain dead.” NATO consensus has been built and sustained by constant diplomacy over the past year to keep all Allies on the same page, including those such as Hungary, that are traditionally less critical of Russia. Since 2014, consensus on Russia has been the centre of gravity of NATO’s deterrence, more important perhaps than the increase of NATO troops on the eastern flank. Imagine the health of NATO a year and a half from now if Trump or a Trump-adjacent leader wins the US presidency and starts once again to attack the Alliance or undercut NATO unity on Russia.

After years of defenestrations, mysterious suicides, poisonings and lengthy jail sentences, there are no rivals or heirs apparent waiting in the wings behind Putin who could assume power in any stable fashion. A dangerous vacuum could emerge.

The West also needs to worry about building stronger bridges with the Global South. The initial international reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine at the United Nations General Assembly was quite united and crossed geographic regions, including many states outside of the traditional West. But condemnation of Russia was not universal. In fact, the unity of the West against Russia has perversely created a situation where some countries, including autocracies such as Saudi Arabia, in-between states like Cuba, major democracies like India, or NATO members like Turkey, have used the war to increase their international leverage and play both sides. They have done this by buying cheap oil, securing a reduction of debt from Russia, moving into the spaces in oil markets created by sanctions, or, in the case of Turkey, holding-up Finnish and Swedish accession to NATO.

Nor is it a given that support from southern states for the West’s position is sustainable over the medium term. In his speech Tuesday, Putin railed against the “decadent West”, and in a similar speech given last October, exhorted African, Asian, and Latin American states to reject the West’s attempts at “domination”. There is a risk that the world could increasingly divide into “the West and the Rest”, an outcome articulated by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov last April as the true aim of the invasion. To avoid this trap, intensive diplomatic engagement across regions will be needed, not only on Ukraine but on other collateral issues. Food shortages, for example, which have resulted from disruption of Ukrainian agriculture and blocking of ports by Russia, hit poorer countries harder. Unless there is a sustained effort to reduce these shortages, the risk of a deeper divide between West and South is real. The West must also reflect on how its response to the war in Ukraine compares to its response to conflicts in other regions where comparable human tragedies are unfolding and work to correct this imbalance.

The longer-term health and credibility of the international system also depends on accountability for violations of international law. The war has exposed and accelerated certain shortcomings that were already underway before Russia’s invasion. Many of the guardrails put in place during the Cold War to manage the risk of conflict – such as the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty or the “Open Skies” Treaty – had already been weakened. Putin announced on Monday that Russia would suspend the New START treaty, the bilateral treaty with the US that puts a cap on long-range nuclear warheads. He has also systematically engaged in nuclear sabre-rattling, including again in Tuesday’s speech. The nuclear taboo that has served the world so well for 70 years will need to be re-established.

The war has also laid bare another weakness in the international system: the brazen flouting by Russia of international humanitarian law, the norms which should at least theoretically guide the conduct of hostilities. Without a determined international push to prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity, the international rule of law will be permanently weakened. The United Nations and NATO will have a job to do in the years to come, focusing on rebuilding the legal guardrails that help manage tensions and ensuring that those responsible for violating international law are held accountable.

Finally, preservation of the liberal international order will also depend on how well the West can preserve our own democracies, building resilience to disinformation designed to misrepresent and deepen political and social divisions inside our own countries. The trend of countries moving away from democracy was already well underway before the war in Ukraine. Freedom House’s 2021 Freedom in the World index shows that democracy has been slipping for the fifteenth consecutive year, and nearly 75 percent of the world’s population lived in a country where democracy declined in the previous year. The 2022 report opened with: “Global freedom faces a dire threat. Around the world, the enemies of liberal democracy—a form of self-government in which human rights are recognized and every individual is entitled to equal treatment under law—are accelerating their attacks.”

In Tuesday’s speech, President Biden again characterized Russia’s war in Ukraine as a clash between democracy and autocracy. The Ukrainians’ robust response to the Russian invasion is not due only to the strength of their military, but also to the strength of their leadership, their capacity in the information space, their engaged citizens and their independent and credible media. Before the Russian invasion, NATO, the European Union (EU), the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the UN and donor states coordinated their aid to Ukraine: the strengthening of military capabilities was accompanied by support for democracy, for a credible civil security apparatus and capacity to counter misinformation. This effort paid off. The lesson learned is that democracy is fragile and that it needs sustained engagement to guard against backsliding, including in our own countries in the West.

As a result of Russia’s war, there is a lot of work for the “non-geographic West” to do to preserve the international order that has kept us safe and prosperous for so long: investing in NATO and the UN, strengthening ties with the Global South, rebuilding the security guardrails that have frayed and shoring up our own democratic resilience. None of this will be sufficient if we don’t support Ukraine for as long as it takes. Otherwise, we send a message to Russia, and to the rest of the world, that armed aggression works.

Kerry Buck, a career foreign service officer, was Canada’s Ambassador to NATO from 2015-2018. She is currently a Senior Fellow at the University of Ottawa and the Bill Graham Centre for Contemporary International History at Trinity College, University of Toronto.