A Keystone Political Economic Indicator for 2024: The Unemployment Rate

By Matthew Mei and Kevin Page

December 12, 2023

The dust is settling on the 2023 Fall Economic Statement (FES) tabled by Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland on November 21st. In the world of numbers, a few were given spotlight by commentators in the post-statement analysis – e.g., budgetary deficit, public debt, and interest on public debt. In the months ahead, the headline economic indicator that may have the largest impact on policymakers will be the unemployment rate.

The word keystone is defined as “something on which associated things depend for support.” The success of the government in holding to its fiscal plan and the Bank of Canada maintaining higher interest rates for longer to reduce inflation will depend in large part on the relative strength of the economy, and the labour market in particular. It is a reasonable bet that budget purse strings will loosen and central bank policy interest rates will fall as the unemployment rate breaks through milestones in 2024 – 6.0%, 6.5%, 7.0% and higher (?).

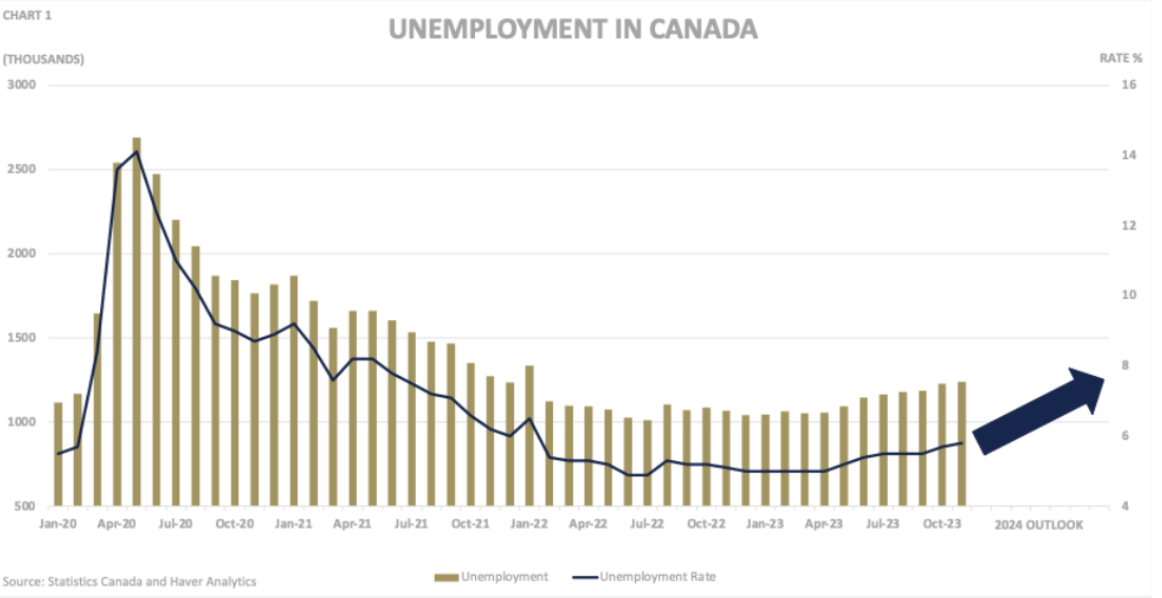

Chart 1

A significant weakening of the labour market will compound concerns around affordability and economic and financial stability. With a federal election on the horizon, political parties are well aware that workers have voting power.

The trend toward higher unemployment is now well established, as indicated by the November Labour Force Survey, reporting a rise to 5.8%, up almost a full percentage point from the summer of 2022. The number of unemployed has risen by more than 200,000 (Chart 1).

This upward drift in unemployment reflects the slowdown in economic growth in 2023. Growth came back stronger than expected in 2021-22 thanks to the vaccine and strong household and business balance sheets bolstered by large government transfers. Growth in 2023 is heavily constrained by high interest rates.

The Bank of Canada’s Business Outlook Survey (BOS) for the third quarter of 2023 indicates that the proportion of businesses citing restrictive labor shortages has reverted close to historical averages. Business indicators reflecting capacity pressures have diminished from elevated levels, with hiring and investment intentions showing a downward trend.

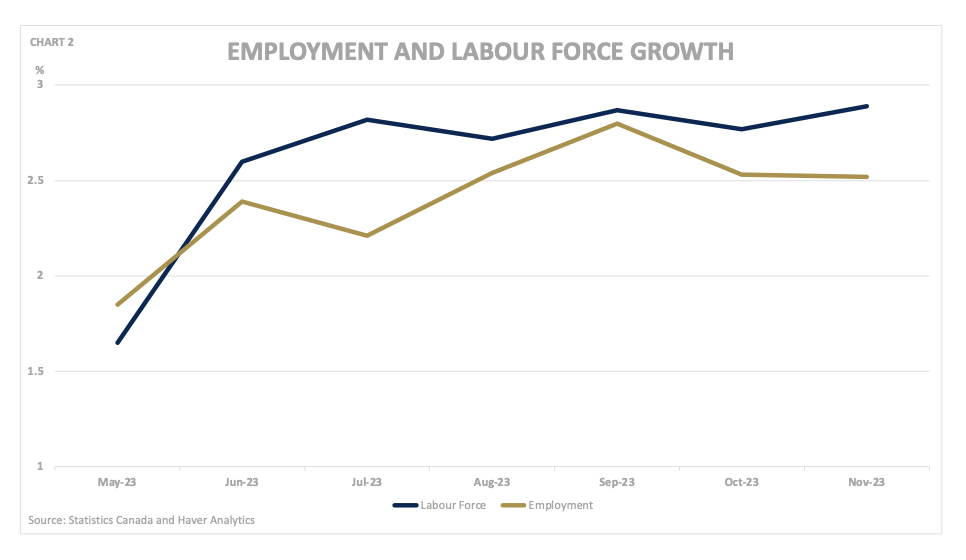

With significant increases in interest rates since 2022, the economy is not firing on all cylinders, a product of monetary policy design to lower inflation. In this macro environment, employment growth cannot keep pace with labour force growth, the labour force being the current population of all people who fulfil the requirements for being employed. This gap is about to get wider.

Chart 2

The Government of Canada’s Immigration Levels Plan for 2024-2026 aims to welcome 485,000 new permanent residents in 2024, 500,000 in 2025 and to plateau at 500,000 in 2026.

It is fair say that Finance Canada sees the rise of unemployment coming. It is one thing, however, to indicate a weakening labour market in the economic outlook and another for political leaders to see hundreds of thousands more people lose their jobs over the next year and to have this information highlighted by Statistics Canada and the media each month through the release of their labour force survey.

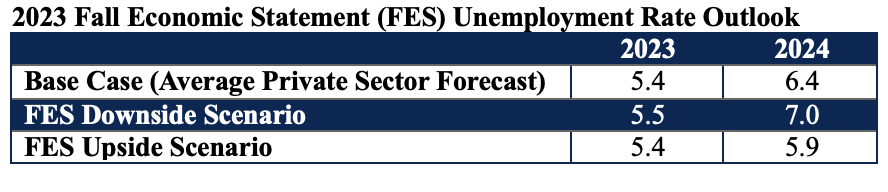

The FES economic outlook included base case and alternative scenarios (Table 1).

Table 1

Source: Government of Canada, 2023 Fall Economic Statement

Source: Government of Canada, 2023 Fall Economic Statement

In the base case scenario, the unemployment rate averages a full percentage point higher in 2024. The peak quarterly unemployment rate would be 6.5 percent. In economic parlance, this would be a favourable soft-landing scenario with more manageable policy impacts (affordability and stability).

In the FES downside scenario, the projected unemployment rate averages 1.5 percentage points higher in 2024. The peak quarterly unemployment rate would crest at 7.0 percent. This milestone would have political (and likely policy) repercussions. This scenario is associated with a relatively modest recession. A peak-to-trough decline in real GDP of about 2 percent – which is less than half the decline experienced in the 2008-09 recession. Given the current level of high (real/after-inflation) interest rates, high household debt and the current weakness in the Canadian economy, this scenario has reasonable probability.

The next year will be a challenging year for Canada’s labour market. The unemployment rate will likely be the keystone political economic indicator.

Matthew Mei is a fourth-year economics student at the University of Ottawa. He is taking a research course at the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy.

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy, former Parliamentary Budget Officer, and a Contributing Writer for Policy Magazine.