A Master Class by a Master, on a Master

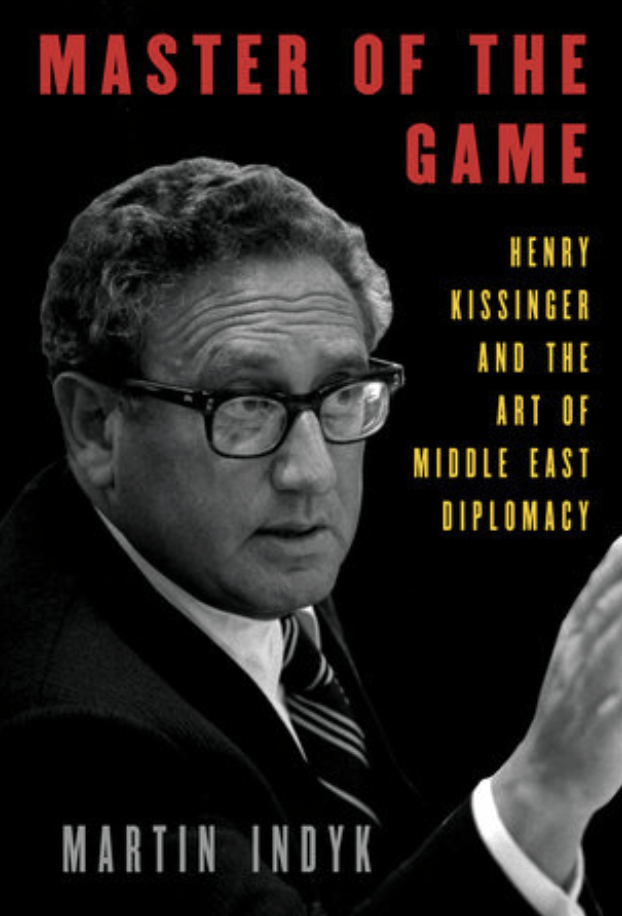

Master of the Game: Henry Kissinger and the Art of Middle East Diplomacy

By Martin Indyk

Penguin Random House, October 2021

Reviewed by Peter M. Boehm

For those seeking insight as to what former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger thinks of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the former US secretary of state and national security advisor, now in his 99th year, penned a piece for the Washington Post in 2014 after Russia took Crimea. In that op-ed, Kissinger wrote that in resolving conflicts in this bilateral dynamic, “the test is not absolute satisfaction but balanced dissatisfaction.”

As a public intellectual, high-level practitioner of realpolitik and foreign policy influencer for over six decades, Kissinger is without peer. His hand was felt with varying degrees of consequence everywhere, but it was his sustained involvement in the complex set of issues that informed and bedeviled the Middle East Peace Process that is the subject of Martin Indyk’s masterful and comprehensive Master of the Game: Henry Kissinger and the Art of Middle East Diplomacy.

To someone who has spent decades immersed in the day-to-day craft of Kissinger’s vocation with frequent forays into high-level diplomacy at the G7 level, reading Martin Indyk on Kissinger is essentially a master class by a master on a master.

Indyk, who, during my time at Canada’s embassy in Washington and afterward, was far and away the most insightful expert on the Middle East in town, whether as a practitioner (assistant secretary in the State Department, twice ambassador to Israel and special envoy for Middle East Peace) or as the affable senior guy with the distinctive Australian accent at the Brookings Institution who selflessly offered his views to Canadian diplomats.

What makes this thoroughly researched study of Kissinger’s influence on Middle East policy so interesting is the frequent juxtaposition and compelling comparisons of Kissinger’s after the Yom Kippur war of 1973 with Indyk’s own travails in the region under presidents Clinton and Obama. It’s a little like the travel diary of one explorer discerning the footprints of an earlier nomad, and it reminds me of TS Eliot dedicating his great poem “The Waste Land” to Ezra Pound, in offering a lyrical study on post-war disillusionment (with a bit of an “I’m not worthy” vibe). Kissinger’s tireless “shuttle diplomacy” (the term was coined to describe his peripatetic approach to mediation) is detailed, as is his charming, cajoling, persuading and prevailing upon of the leaders of Egypt, Syria and Israel to relinquish territory in the pursuit of a viable, steady state of non-belligerence.

Indyk describes this approach to negotiation as the “skillful manipulation of the antagonisms of competing forces.” He does not shy away from criticism: Kissinger should have done more to include efforts Jordan’s King Hussein to represent Palestinian interests in addition to Yasser Arafat’s Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). But with a variety of international spinning plates to keep aloft and Watergate consuming President Richard Nixon at home, Kissinger’s diplomacy really did become “the art of the possible”.

To great effect, Indyk describes Kissinger’s use of front, back and side channels to exert both sustained influence and pressure on the key actors in the Middle East as well as on the Soviet Union. As both national security advisor and secretary of state, Kissinger possessed an extraordinary amount of power and influence, serving a beleaguered and addled president on the cusp of his Watergate resignation. Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, also came to rely completely on Kissinger’s judgment. Indyk’s book is at once a marvellous, fast-paced rendition and analysis of international events and a paean to the vocation of diplomacy as practised by a master. It is historical but also written by a virtuoso practitioner who inserts reference points in US Middle East diplomacy in which he was deeply involved that give this comprehensive narrative a contemporary patina.

As a former career diplomat, two aspects of Kissinger’s story stand out for me. First, Indyk concludes that it was Kissinger’s relentless, deft and often brilliant personal diplomacy that built a framework for peace that lessened the existential threat against Israel, thereby providing the path for a far closer relationship with the US and its allies. This, of course, still holds. Second, Kissinger developed peace mechanisms and approaches based in United Nations Security Council authority; in short, the rules-based international order to which all players, including the then-Soviet Union, agreed.

This framework — these well-established underpinnings which have served the conduct of international relations so well since 1945 — seems under great threat today. Perhaps Kissinger’s notion of “balanced dissatisfaction” will have to become our reference point. The question is how to achieve it.

Senator Peter Boehm, chair of the Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade, is a former ambassador and deputy minister who served as Canada’s sherpa for six G7 meetings.