A Personal Pathway to the Pinnacle of Power

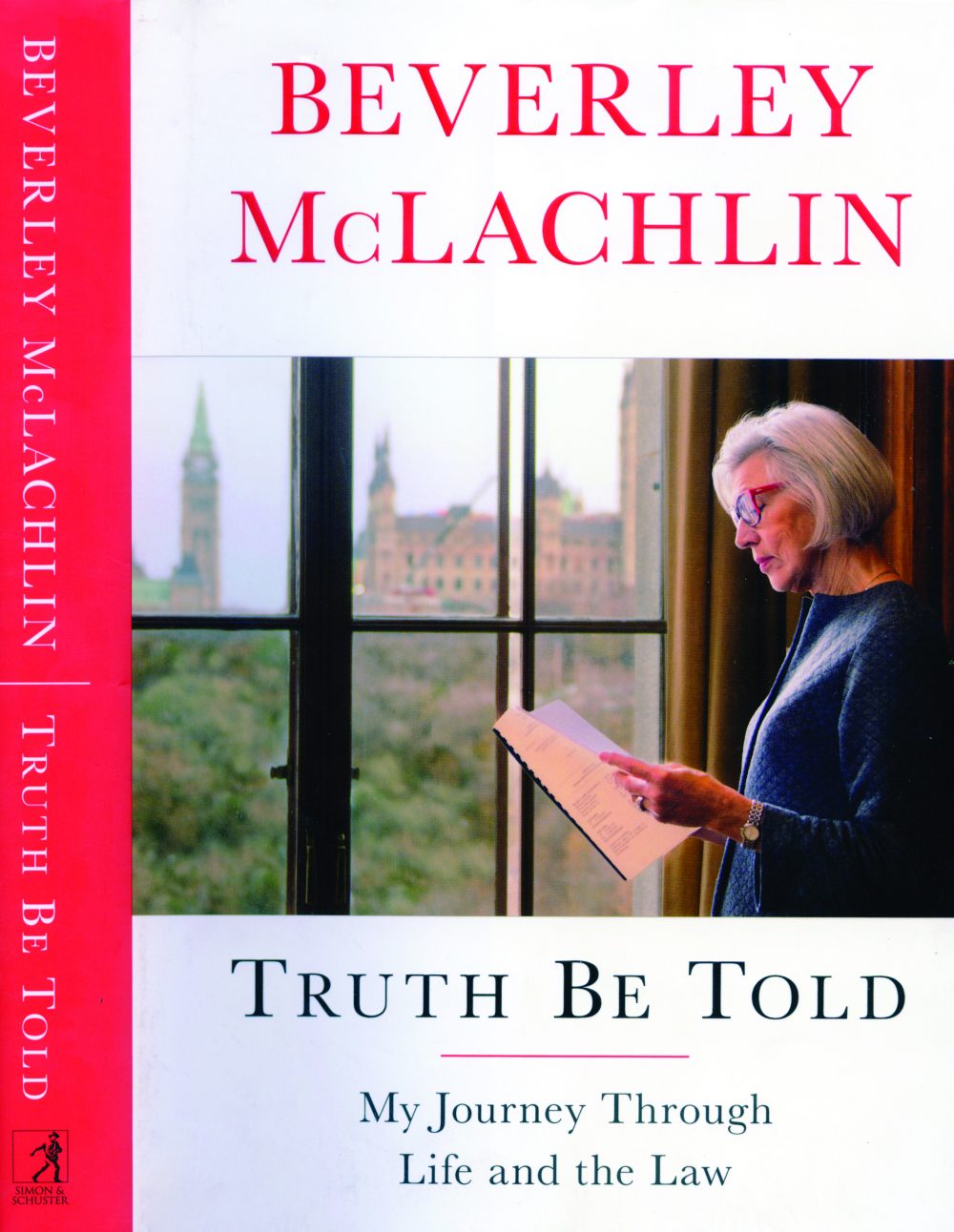

Beverley McLachlin

Truth Be Told: My Journey Through Life and the Law. Toronto: Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Review by Lori Turnbull

In the pages of Truth Be Told, retired Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin gives the reader an open and candid account of her life, from her childhood in Pincher Creek, Alberta, up until a post-retirement vacation in Tuscany. This book is not a chronology of her work as a judge. Instead, it is an opportunity to get to know her and to understand the personal, intellectual, and ethical motivations that have driven her life and career.

In the pages of Truth Be Told, retired Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin gives the reader an open and candid account of her life, from her childhood in Pincher Creek, Alberta, up until a post-retirement vacation in Tuscany. This book is not a chronology of her work as a judge. Instead, it is an opportunity to get to know her and to understand the personal, intellectual, and ethical motivations that have driven her life and career.

Studious, hardworking, and self-reflective from a young age, McLachlin takes nothing for granted. She is hopeful and optimistic by nature, but she admits that she “never dared dream” of the life she came to know on both the personal and professional fronts. After carefully weighing the pros and cons, she left her tenured position at the University of British Columbia law school to accept an appointment as a judge in the County Court of Vancouver at just 37 years old. McLachlin was promoted to the Supreme Court of British Columbia just months later. She was appointed to the British Columbia Court of Appeal in 1985, was made the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of British Columbia in 1988, and was nominated to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1989, where she became Chief Justice in 2000 and remained so until her retirement in 2017. Her nearly 40-year career as a judge made an impact on Canadian jurisprudence that is nothing short of profound.

Her approach to the law has been influenced by the work of American liberal philosopher John Rawls, whose central contribution was his thinking on “justice as fairness.” The law should afford maximum liberty to individuals so long as that liberty does not infringe upon that of another. This line of argument echoes the basic harm principle that John Stuart Mill articulated. Further to this, McLachlin believes that treating people as “equals” ought not be confused with treating people “the same.” True justice requires consideration of context and circumstances, and merely treating people as though they are “the same” amounts to wilful blindness to truth.

Throughout her life as a lawyer, law professor, and judge, McLachlin viewed the law as an equalizer and as a mechanism for fairness that is and ought to be available to all of us. About halfway through the book, she reveals her inner discourse around the concept of equality and its elusiveness for many people, including women. She demonstrates lifelong mindfulness of the struggles that women face, particularly those who bear the intersecting burden of poverty. Justice McLachlin’s court helped to establish pay equity in Canada, including with the Public Service Alliance of Canada v. Canada Post Corp. decision in 2011 that awarded damages to a group of employees after a claim was originally filed against Canada Post in 1983.

McLachlin sat on the Supreme Court for many of the most pivotal Charter cases in the country’s history. Her decisions have had definitive effects on key aspects of constitutional law, including the aforementioned pay equity issue, the scope of free speech, the right to a doctor-assisted death, the role and reform of the Senate, and Indigenous rights.

One of McLachlin’s early decisions on the Supreme Court addressed a matter we grapple with frequently today: the prevalence of fake news and the state’s role in protecting us from it. In R. v. Zundel (1991), the question at stake was the constitutionality of section 181 of the Criminal Code, which was the “false news law” that prohibited spreading “a statement, tale or news” that a person knows to be false and is likely to cause “injury or mischief to a public interest.” McLachlin penned the majority decision that struck down the law for its vagueness and, in her memoir, writes that the Zundel decision, when considered together with the earlier Keegstra decision that upheld the law prohibiting the wilful promotion of hatred against an identifiable group, struck a balance between the right to free speech and the protection of minorities from harm.

Throughout her career, Justice McLachlin has been known and respected not only for her decisions but also the straightforward, accessible style in which she wrote them. Not one for using jargon, which is an exclusionary, elitist tactic designed to leave people out of conversations rather than draw them in, McLachlin was committed to writing decisions in plain language and she encouraged her peers to do the same.

Given the daunting list of accomplishments that have defined her extraordinary career, McLachlin would have every right to publish a book that situates her, front and centre, as a brave pioneer and a key player in the evolution of the law in Canada, particularly with regard to equality and human rights. After all, she is that brave pioneer. But her tone is unwaveringly modest. She is refreshingly upfront about the times in her life that she has struggled. As she was building her career, she was also grieving the loss of her mother, and then her father, and then her husband. She found herself confronting unexpected sadness when her son was an infant. She knows the acute stress of trying to make ends meet. The richness of her own life experiences readied her as a judge and enabled her to bring empathy to the bench. She could relate genuinely to the people making cases before her.

Truth Be Told adds welcome texture to the significant legacy of a Canadian policy leader. Beverley McLachlin’s forthright, generous style allows the reader to understand more not only about her, but about the judicial decisions that have shaped Canada’s law and Constitution in the post-Charter era.

Contributing Writer Lori Turnbull, a co-winner of the Donner Prize, is Director of the School of Public Administration at Dalhousie University.