A Prescription for Climate Progress: Stubborn Optimism, and More Stubborn Commitment

Between criticism from the left that the Trudeau government is doing too little on climate change and criticism from the right that it is doing too much, it can be hard to discern precisely what it has done and where climate policy expert Dan Woynillowicz provides a briefing.

Dan Woynillowicz

Heat domes. Atmospheric rivers. In 2021, my vocabulary expanded in ways I hadn’t anticipated. Living in British Columbia, I witnessed the cascading impacts to services and supply chains that accompanied the heatwaves, wildfires and flooding, and felt the sense of helplessness shared by most British Columbians as the toll in lives and livelihoods ticked upwards with each disaster.

While some commentators characterize these catastrophic weather events as our “new normal,” climate scientists remind us that this would imply a new and static stability that simply doesn’t exist. If anything, the “new normal” is that there is no normal anymore. The amount of carbon pollution we have and continue to pump into the atmosphere is changing our climate and the weather systems it fuels.

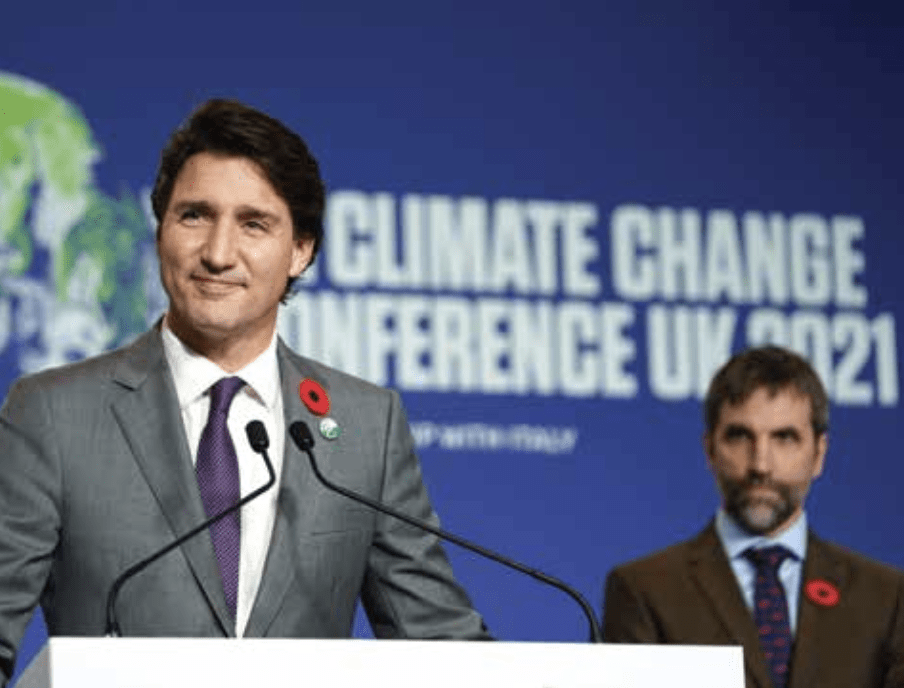

This isn’t to suggest that efforts to cut carbon pollution and take climate action are futile. To the contrary, it simply reinforces the imperative to strengthen and accelerate efforts. As Prime Minister Justin Trudeau noted in his speech at the COP26 climate change negotiations in Glasgow, “The science is clear: we must do more, and faster.”

To Canada’s and the Prime Minister’s credit, these words aren’t simply good intentions, but are backed up by a track record of effort, accompanied by clear and specific commitments to do more. To some, this might seem a controversial statement. You don’t have to look far to find criticism of the Canadian government’s climate efforts – that it has been too slow, too weak, and simply hasn’t reduced national carbon pollution (at least not yet). As leaders of the NDP and Green Party trumpeted in last fall’s election, the Trudeau Liberals were more about pretty words than real action.

But as Charles Dickens wrote in Great Expectations, “Take nothing on its looks; take everything on evidence. There’s no better rule.” In this spirit, a brief recap is in order:

Following their 2015 election win, the Liberals brought Canada into the Paris Agreement and drew provinces together behind the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. They introduced a national price on carbon pollution, defended it up to the Supreme Court of Canada, and have committed to a schedule of increases out to 2030. They have secured a phase-out of coal-fired power at home and championed the Powering Past Coal Alliance internationally, advanced a Clean Fuel Standard to clean up fuel for gas vehicles, and made major strides to enable more Canadians to ditch their gas vehicles, buy electric replacements and keep them charged.

Their 2019 election platform promised even more, and they delivered. The Healthy Environment, Healthy Economy climate plan released in late 2020, and supported by new investments in the 2021 budget, put Canada on track to achieve a 36 percent reduction below 2005 levels by 2030 (beating the original Paris target of 30 percent). They could have coasted but understood more action is both needed and expected of Canada. So, in keeping with the Paris Agreement requirement to review and increase ambition on a five-year cycle, they filed a new target of a 40 to 45 percent pollution reduction by 2030.

Yet despite all this effort, carbon pollution isn’t yet falling in Canada. What gives?

Regrettably, what the federal government does (or doesn’t do) is not the sole determinant of emissions in our federation. It’s a shared responsibility with provinces, and during the Liberals’ tenure, the provinces that contribute the most pollution — Alberta and Ontario — both saw changes in government that led to a rollback of provincial climate efforts and a deliberate effort to stymie federal efforts.

But equally significant is the reality that policies, programs, and regulations take time to design and, when implemented, don’t create change overnight — there is an unavoidable lag. But consult experts, and they’ll tell you that the policies now being advanced will begin to reduce pollution in short order, and those reductions will grow and accelerate as they take hold.

Fortunately, we don’t just have to go on faith and expert analysis. The passage of the Canadian Net zero Emissions Accountability Act will provide Canadians with more clarity than we’ve ever had about what efforts the government is making, and of the expected results from those efforts. While most public and media attention to this legislation focused on its targets, its real value is in the obligation it creates for the government to establish and publish detailed plans, and to prepare progress reports for milestone years, with the first report due by no later than the end of 2023.

The first of these plans was intended to be due by the end of 2021 but considering the timing of the federal election and COP26, the government exercised its right to a 90-day extension and so will deliver it by the end of March. The plan will not only incorporate all the policies and programs described above, it will also include the big promises made in the Liberals’ 2021 election platform:

- Mandating the sale of zero-emission vehicles so that 100 percent of new light-duty vehicles (cars, pickups, etc.) sold in Canada are zero emission by 2035 and at least 50 percent by 2030;

- Developing emissions standards for heavy-duty vehicles that are aligned with the most ambitious standards in North America, and requiring that 100 percent of selected categories of medium- and heavy-duty vehicles be zero emission by 2040;

- Capping emissions from the oil and gas sector at current levels and requiring that they decline at the pace and scale needed to get to net zero by 2050;

- Developing a plan to reduce methane emissions across the broader Canadian economy in support of the Global Methane Pledge and the goals in Canada’s climate plan, reducing oil and gas methane emissions by at least 75 percent below 2012 levels by 2030 through an approach that includes regulations, as well as regulating methane landfill emissions and reducing agricultural methane emissions; and

- Transitioning to a net zero emitting electricity grid by 2035.

While many of these commitments include targets that extend beyond 2030, the plan is required to include projections of the annual greenhouse gas emission reductions resulting from those combined measures and strategies—including projections for each economic sector. For the first time, there will be clear and quantitative transparency around the scale and timing of emission reductions, which Canadians can use to both hold the government accountable and to evaluate its progress. By the next election, whenever it may be, we should be able to see how big the gap is between ambition and action, words and results.

Finally, three decades after Canada ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992) and two decades after Canada ratified its first emission reduction commitment in the Kyoto Protocol (2002), we are beginning to get the institutional and administrative pieces in place to track federal climate action efforts. And I say “beginning” because the job isn’t yet complete. As helpful as the Net Zero Emissions Accountability Act is in establishing plans and tracking performance against them, it doesn’t explicitly require or drive the changes in governance—both the form and function of government—needed to execute these plans.

But on this front, there are some signs of progress nonetheless, from the establishment of a Cabinet Committee on Economy, Inclusion and Climate to a focus on climate action in the mandate letters of all ministers, including specific deliverables for some. Similarly, climate change is increasingly being considered in everything from government procurement to policy development, and the Healthy Environment, Healthy Economy plan pledged to “Apply a climate lens to integrate climate considerations throughout government decision-making” by ensuring government decisions “consider climate ambitions in a rigorous, consistent and measurable manner…that ensures that government spending and decisions support Canada’s climate goals.”

Following the 2021 election, the decision to shift the former environment minister, Jonathan Wilkinson, to the Natural Resources portfolio, and Steven Guilbeault to Environment was broadly perceived as a strong signal that the government intends to move quickly on its campaign promises. Notably, the creation of a parliamentary secretary role, held by Julie Dabrusin, to work with both the natural resources and environment ministers creates a connective tissue between these ministries that holds interesting potential for better political integration.

Meanwhile, in the public service, the government has established a climate secretariat within the Privy Council Office (PCO), though its mandate and influence aren’t yet clear. Optimally, it should have a focus on policy integration and efficiency, with responsibility for navigating competing priorities, trade-offs, and synergies among federal departments, helping to develop climate plans and shepherding their implementation.

A recent report by the International Institute for Sustainable Development and the Canadian Institute for Climate Choices, Greater than the sum of its parts: How a whole-of-government approach to climate change can improve Canada’s climate performance, quite rightly notes that achieving Canada’s climate targets “will require the active involvement of departments as disparate as Finance, Infrastructure, Transport, Natural Resources, Environment and Climate Change, Agriculture and Agri-Food, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs, Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, Employment and Social Development, and others, necessitating a coordinated approach to ensure coherent implementation of climate strategy.” Informed by detailed case studies of whole-of-government efforts in the UK, US and B.C., it offers important recommendations for implementing a cohesive and effective whole-of-government approach to climate change, which the Prime Minister’s Office and PCO would do well to follow:

- The success of a whole-of-government climate initiative depends on sustained executive leadership directing departmental priorities and inter-departmental coordination.

- An effective whole-of-government climate initiative requires adequate funding, a clear mandate, and capacity to enact change across departments.

- An effective whole-of-government climate initiative requires effective and empowered personnel acting in whole-of-government structures.

- The mandates of participating departments must align, or be brought into alignment, with the mandate of the whole-of-government climate initiative.

- A whole-of-government climate initiative should report publicly on its progress and be as transparent as possible about its deliberations, findings, and research.

Over the course of its first six years in office, the Liberal party effectively advanced numerous policies and programs that promise to deliver emission reductions in the coming years. Equally important, they created a system of transparency and accountability we have never previously had at the federal level. Hopefully, by the time the next election rolls around, Canadians will be able to get a clear view of what has been promised, what has been delivered, and whether the two line up.

Much as we might hope that B.C’s climate annus horribilis was an exception, years without climate-fuelled disasters somewhere in Canada are more likely to be the exception. Nonetheless, a Leger poll from November 2021 found that 75 percent of Canadians believe we still have time to put measures in place to stop climate change. They, like me, appear to be what Christiana Figueres, the diplomat who brokered the Paris Agreement, calls “stubborn optimists.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote that, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless yet be determined to make them otherwise.” In the era of climate disruption, these words ring true, although in my view it’s less a measure of intelligence than emotional fortitude and resilience.

What all of this means for the federal government is that expectations are high for it to deliver on its climate action ambitions and commitments, and it has the public support it requires to move forward assertively. But adding to the challenge is the obvious imperative to not only try to cut pollution to prevent the worst impacts of climate change, but to prepare for and manage the impacts that climate change is already imposing. Consequently, in parallel to advancing an ambitious policy package to cut pollution, it will need to deliver reactive emergency support in response to floods and fire, while simultaneously making investments in climate-proofing infrastructure and delivering programs that will make Canadians safer and more resilient in the face of a changing climate.

It’s no small task, but I remain stubbornly optimistic.

Contributing Writer Dan Woynillowicz is the Principal of Polaris Strategy + Insight, a public policy consulting firm focused on climate change and the energy transition.