A US Election Like No Other

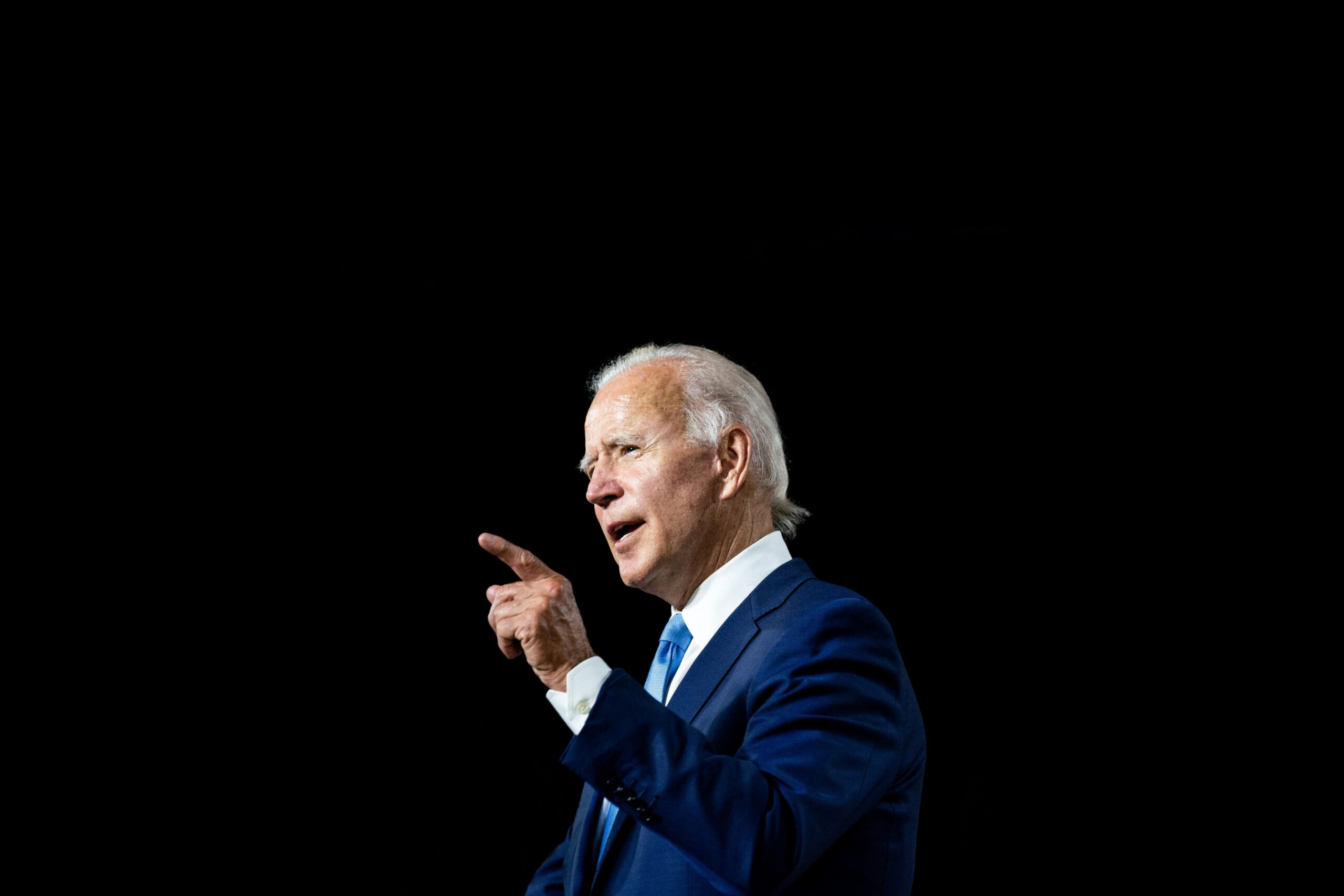

‘For Canadians, popular preference remains very much for Biden’s America,’ writes former ambassador to Russia, the EU and the UK Jeremy Kinsman/Shutterstock.

‘For Canadians, popular preference remains very much for Biden’s America,’ writes former ambassador to Russia, the EU and the UK Jeremy Kinsman/Shutterstock.

‘When America sneezes, the world catches a cold’ has morphed in the age of Trump into ‘When America loses its mind, the world grabs the Xanax’. There is no-one more qualified to assess the global stakes of this election than our own foreign policy sage, Canada’s former ambassador to Russia and the EU, and former high commissioner to the UK, Jeremy Kinsman.

Jeremy Kinsman

August 13, 2023

This US presidential election prompts in America and abroad unprecedented degrees of anxiety. The stakes could not be higher, including for America’s image and influence internationally.

Apart from his advanced age, Joe Biden is a fairly typical candidate for second-term re-election, with a generally commendable first-term record, especially on all-important economic indicators. Biden overcame congressional gridlock to achieve landmark legislation, among others; Acts on infrastructure, inflation reduction and clean energy, and “Chips and Science.” They helped the economy charge out of the COVID slump. A resurgence in manufacturing, particularly in Western Republican-leaning states contradicts the worn-out “Make America Great Again” slogan of his putative rival. Goldman Sachs has cut its estimate of the probability of a recession in the next year from 25 percent to 20 percent.

And yet, the calcification of US partisan antagonism into two parallel information systems results in polls showing widespread dissatisfaction with Biden’s “handling of the US economy.” Stepping back from the noise of US politics, one sees two opposing narratives.

Biden’s internationalism accompanies a domestic policy design geared to equipping the US for the future; in research, science, and education, where America had lost its preeminence. Donald Trump’s much more isolationist messaging is anti-modern and grievance-based, hostile to change, to bicoastal urban “elites,” and to science itself. Evangelical antipathy to non-traditional progressive social and sexual identity agendas combines in Trump’s GOP with libertarian antipathy to the reach and role of interventionist government in an awkward but vocal alliance against “socialist” big Democratic governance.

The Trump GOP’s abhorrence of globalization and “cultural” change does mirror suspicion elsewhere in the world. Its xenophobic and populist appeal is replicated by personalist autocrats in the global South, in Russia, and China, who also exploit inward, tribal, traditionalist, and nationalist emotions.

But Pew Institute global surveys indicate a clear preference for Biden’s more globalist approach among the world’s public. Among G-7 partners repelled by “America First, ” Pew indicates an average 59 percent of the public hold “favourable” views of the US today, compared to about 34 percent in Trump’s last year as US president in 2020.

Their leaders are even stronger in their preference for Biden. None of America’s world partners wants to re-live Trump’s erratic, jingoistic, uninformed, and disruptive performance in his first term. Most leaders had persuaded themselves in 2016 despite Trump’s unusual rhetoric, that he would “normalize” once in office, that the US would conduct international affairs in continuity with the broad lines of US approaches from previous administrations. Specifically, they assumed the US would remain committed to NATO as the primary channel for American engagement with Europe. Trump trashed these assumptions.

The scar tissue of Trump’s international disruption has barely healed. US partners have noted reports that the Trump network of research foundations and think tanks is preparing a blueprint for a second term that will take his vision of “drain-the-swamp” radical change in US governance all the way to wholesale institutional and regulatory upheaval. “America First” will be methodically re-implemented. Especially worrying is recent CNN polling indicating that only 28 percent of GOP voters support additional funding for Ukraine as opposed to 62 percent of Democrats. Vladimir Putin’s revised game plan surely hopes for Trump’s election as a kind of Hail Mary evasion of accountability for Russia’s reckless, costly, and failing invasion.

In consequence, US partners are quietly discussing a Plan B for cooperation without the US on democratic and international solidarity, should Trump win in 2024. Compensating for expected US isolationism, they will defend multilateral cooperation as globalists, and especially crucial international commitment to maintain support for Ukraine’s sovereignty.

China, whose anti-US rhetoric had become stinging, had aligned with Putin’s resistance to America’s “unipolar” preeminence. But, as the Chinese economy begins to stumble, China now seems increasingly concerned by global instability. The Biden administration has been re-connecting diplomatically to China in an effort to stabilize at least the floor of the all-important relationship to prevent further deterioration.

The Biden presidency gets higher marks for international cooperative leadership from foreign leaders than any in my professional lifetime.

While a few autocratic leaders around the world still mimic Trump’s style, admire his election denialism, and resent US commitment to human rights, the Biden presidency gets higher marks for international cooperative leadership from foreign leaders than any in my professional lifetime going back to Lyndon Johnson, with the possible exception of internationalist George H.W. Bush. Presidents Reagan and Obama, with different emphases, each lifted America’s game and prestige in world capitals, but each also created doubts about consistency and follow-through. Biden’s foreign policy brain trust of National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, CIA Director William Burns and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, among other, has provided the most credible, attentive, and thoughtful leadership of any.

So, why isn’t Biden running away with the race? There are acres of analysis of the depth and width of US anti-modernist pushback that Trump’s candidacy excites among Americans who feel “left behind.” The capture of the Republican Party by Trump’s populist, grievance-based, and polarizing narrative has been monetized by siloed US media outlets and social media to ensure the loyalty of the faithful with the threat of more adverse change if Democrats are re-elected.

Biden’s counter-narratives have played both on Trump’s vivid threat to US democracy, and to core substantive policy issues — health care, the economy, global security. But the whole country is conscious that Biden will be days short of 82 on election day. Trump will be 78. It has encouraged a GOP dog-whistle sub-campaign against Vice-President Kamala Harris. Polls show that a majority of voters would prefer two other candidates altogether, but both re-nominations seem locked in. However, in these times, anything can happen. Surprise is normal. We cannot presume where we shall be in November next year.

Trump’s active indictments for criminal offences are without precedent for a presidential candidate. He boasts that each chapter in the indictment “witch hunt” only propels him higher in the polls. His “jury” will be “the people.” But his popular support will leak moderate Republicans when the evidence for criminal charges to be tried in Washington and Atlanta reveals clearly how he knowingly tried to remain illegally in office.

Despite some polls indicating a dead heat, Trump does not have a decisive majority of the American public behind him. He never tried to broaden his appeal by moderating his message, counting on his core clientele of white, poorer, less educated, mostly older and mostly male and evangelical traditionalist voters in non-urban and non-coastal America, with its disproportionate share of votes in the electoral college, to carry him over the top. It remains hard to see how, when the remnants of more moderate traditional Republicans back away, as 5 to 10 percent of his prior voters also seem inclined to do. The No Labels third-party plan is trying to sequester such refugee centrists to keep them from Biden, but skepticism persists that this will get traction.

Nonetheless, deeply concerned foreigners cannot rely complacently, as they did in 2016, on Americans to do the right thing. Should Trump somehow win, the world will change, and with it, the world’s estimate of America and Americans. On the other hand, should Americans refute Trump’s divisive message, the revalidation of American democratic and judicial institutions will project their exemplary value to an expectant but hesitant world.

For Canadians, popular preference remains very much for Biden’s America. That ought to help Justin Trudeau, whose team parried Trump’s economic nationalism over NAFTA. But while Trudeau is now the dean of G-7 leaders, longevity in office hasn’t made him an international leader of consequence. Nor is longevity a winner domestically. Polls show less enthusiasm in Canada for his running again than there is in America for Biden.

He seems determined to, convinced he campaigns well — he does — and that his opponent, Pierre Poilievre, has enough Trumpish anti-elite populism about him and among his core Conservative supporters to be an easy target. That’s his gamble. It will be a raucous election cycle, on both sides of the border.

Policy Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman is a former ambassador to Russia, the EU and Italy, as well as a former High Commissioner to the UK. He is a Distinguished fellow of the Canadian International Council.