All’s Well that Starts Well

Douglas Porter

January 13, 2023

For the first time in three years, the Economic Club of Canada held its annual Economic Outlook event in person this morning—please refrain from commenting on the choice of a Friday the 13th for the shindig. Billed as a meeting of the greatest economic minds in Canada—and me—it features the chief economists from the largest chartered banks, to consider the prospects for the year ahead for the Canadian and global economies and financial markets. The turnout was excellent (over 800), despite challenging weather and what’s normally light attendance in the downtown core on Fridays. And that strong turnout likely reflects the exceptionally keen interest in the outlook, given the many cross-currents and headwinds confronting the global economy. Accordingly, below are some of the major issues addressed in the session, and some of the viewpoints.

Recession or not

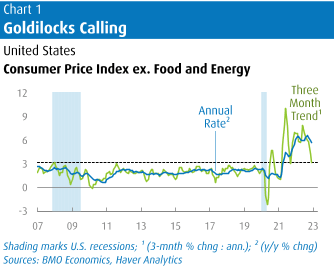

Dealing with the elephant in the room right off the bat, panellists danced around the specific forecasts for GDP, but the consensus was that even if we don’t fall into an outright recession, growth will be minimal this year. Our official call is in the shallow recession camp, and we are at the low end of consensus calling for zero GDP growth in both Canada and the U.S. this year (the average call is now 0.4% for Canada, after around 3.5% last year). However, bluntly, the chances of the much-ballyhooed soft landing are rising by the day as U.S. underlying inflation ebbs (Chart 1). This week’s key release saw core CPI post a moderate rise for the third month in a row, further fuelling talk of a Goldilocks outcome in the wake of last week’s friendly employment report (steady job growth, moderating wages).

Will the Bank of Canada (and the Fed) go too far?

The most widely-cited risk was that policymakers would indeed err on the side of tightening too much, rather than too little. Even we—who have been consistently on the high side of the inflation call for the past two years—have been impressed by recent U.S. inflation trends (we chopped our call on U.S. CPI this week, closer to consensus). Still, we don’t believe that the central banks have overdone it yet. Short-term interest rates are still below inflation trends, and the ongoing strength in the labour markets certainly gives no sense that rates have gone too far. Having said that, our official call on the Bank of Canada is just one more hike of 25 bps this month, and then a move to the sidelines for the rest of 2023. Similarly, we now look for 25 bp moves from the Fed at its first two meetings (previously we had a 50 bp hike on Feb. 1), and then a pause for the rest of the year. We believe that will be enough to tame inflation—if the central banks feel the need to do more than that, then yes it will eventually be going “too far”.

Whose economy is more at risk—Canada or the U.S.?

There was no consensus on this issue, and our forecast happens to have the two economies locked in a tie for growth this year. One very reasonable view was that because of Canada’s much higher household debt levels, and its much larger dependence on housing, that it is clearly at greater risk in the wake of the most aggressive rate hikes in decades. The counterpoint was that much stronger population growth flatters Canada’s consumer spending outlook, as does the fact that there is still more catch-up to go from the restrictions of the past three years.

I also chimed in that the fiscal outlook may favour Canada in the short-term: finances have recovered quickly here, in part thanks to the commodity boom, and provinces have rolled out impressive support, while Ottawa still has many medium-term spending priorities. On the flip-side, the U.S. budget deficit has widened again to more than $1.4 trillion (or 5.6% of GDP) in the past 12 months, and all eyes are turning to a potential showdown over the debt ceiling later this year—especially after the struggle to even elect a speaker in the House last week.

Why is the loonie struggling, and will it improve?

No commodity currency thrived last year, even when resource prices bolted higher in the wake of the Ukraine invasion. And then they were pummelled in the second half of 2022 as concerns over the global economy mounted and commodities sagged. For the most part, this was a U.S. dollar story, as the greenback simply steamrolled every currency. But the loonie even lost ground against the euro on net last year—not what you would expect given the massive energy challenges facing the European economies. Most commodity currencies have started this year on a slightly better footing, supported by China’s reopening and a somewhat more moderate outlook for Fed policy. We look for the Canadian dollar to strengthen modestly further this year, albeit with a year-end target of just around $1.30 (just under 77 cents).

Will commodities provide some support for domestic markets?

This is no normal cycle, and some of the standard playbook assumptions are not going to work this time. And one potential oddity is that commodity prices may hold up surprisingly well even in the face of a much cooler global economy. Some supportive factors for resource prices are: 1) the policy changes in China, both the reopening and the general slant to more growth-friendly measures in recent weeks; 2) a softening U.S. dollar; 3) green-energy-driven demand for some commodities (e.g. copper, nickel, and lithium) and 4) specific supply considerations, such as the Ukraine conflict or OPEC’s determination to keep crude prices firm. The recent comeback in copper prices is a particularly notable development, which at the very least raises some doubts on talk of a global recession.

Is Canada in a housing bubble?

The short answer was “not any longer”. Nationally, prices are down in the double digits from last February’s frenzied high, with much deeper drops in many Ontario cities (which had been the hottest of the hot in the pandemic). While most panellists expected further declines in prices this year, as the market more fully digests the steep rise in interest rates, some were quite optimistic on the medium-term outlook—largely due to relentless strength in population growth. There was some debate over just how much a tight supply situation was the root cause of the price run-up; as usual, we made the case that overheated demand was the driver, and that new supply has actually been quite robust (also noting the record 300,000+ units under construction).

What keeps you awake at night?

Longer-term concerns included Canada’s woeful productivity performance, the lack of planning around strong population growth, and the clear possibility that inflation may yet surprise us all to the high side again—which would indeed necessitate much stronger action from the central banks, and the prospect of a much harder landing for the economy. Personally, just to end things on a cheery note, I suggested that all of these economic concerns are minor compared with some of the geopolitical risks the global economy may need to contend with in the years ahead—whether it’s from China, Russia, Iran or North Korea.

Anything positive to end on?

Not wanting to end on that sour note, a few pointed to the amazingly healthy job market, as well as the incredible resiliency that many economies displayed during the deep challenges of the past few years. Fully agreeing with those comments, I also noted the robust start to 2023 in financial markets—for both equities, bonds, commodities, and, yes, even crypto—which hints that investors are raising the odds of the economy achieving the elusive soft-landing scenario in the year ahead. While that’s not our base case, it is definitely encouraging that underlying inflation does appear to be ebbing, and wage growth remains moderate, raising the odds of a more positive outcome for the economy and markets this year.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.