A Defining Moment for the United Nations

Reuters

Reuters

Bob Rae

March 20, 2022

Vladimir Putin’s decision to escalate his illegal war against Ukraine has created a global turmoil as serious as any the world has experienced since the end of the Second World War. It raises the most fundamental questions about the nature of the world order, and will force a major reassessment by every country in the world, including Canada, about how global governance and the enforcement of international law should work in the 21st century.

There is no overstating the seriousness of the moment. It is right to point out that there are many other bloody conflicts going on in the world right now, from Myanmar to Syria to Yemen to Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa across the Sahel, and that those disputes are also leading to the displacement of tens of millions of people from their homes — the greatest humanitarian crisis in modern times. But it is true to say that no conflict so clearly reveals this era’s unprecedented challenges to the institutional structures we thought would keep us from the brink of existential conflict.

More people have died in Africa’s long civil wars over the last forty years. The impacts of some conflicts are literally buried in the ground as mass graves and suppression of outside media and humanitarian workers prevent us from understanding what is going on. In each of these conflicts, the United Nations struggles to intervene and engage to begin the vital repair work that strives to deal with the underlying causes of conflict.

The much-thumbed copy of the Charter of the United Nations and the statute creating the International Court of Justice that I carry around in my pocket has led me to try to understand better what the world thought it was creating in 1945. The core strengths and central weaknesses of that postwar structure have now been exposed by assaults on its integrity from weapons that could not have been foreseen more than half a century ago.

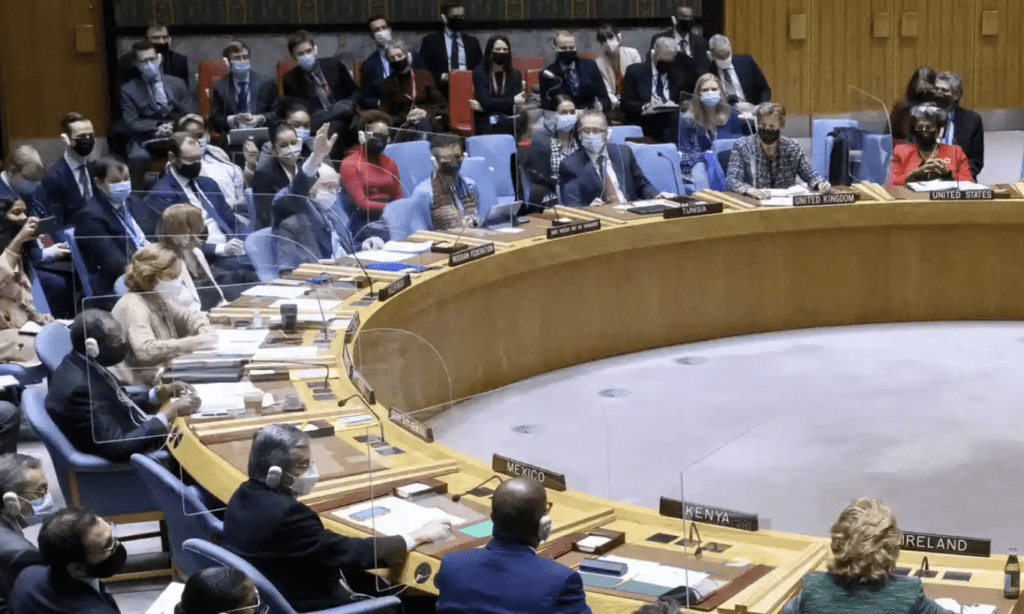

The negotiation of our global governance structure was controlled by “The Big Three” Second World War victors — the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union — as the vision of a new global order that attempted to strike a balance between those with power and everyone else. Adding China and France to create the “P5” while birthing a Security Council with five permanent vetoes meant deadlock and gridlock were cooked into the operating system of the institution.

But to the vetoes at the legal nucleus of the institution — whose consequences in terms of hierarchy, secret parleys, “leave this to us” are everywhere to be seen and felt — lies another, more critical veto, and that is the possession of the means of mass destruction by a limited number of countries that affects how things actually work in the “real world”. The end of nuclear hegemony created a deadlock more profound than a raise of the hand at the Security Council, and it is that fact that lies at the heart of the current challenge in how to deal with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression.

It is readily apparent that President Putin cares as much about human life, human dignity, personal freedom and the rights of other peoples as did his political predecessor and spiritual ancestor, Josef Stalin. As he has told us, his opponents are but “gnats” to him.

Recent tactics adopted by Russia, China and other interests aiming to degrade democracy and replace the rules-based world order with one more amenable to their interests and less accountable to humanity did not exist and could not have been foreseen amid the debris of Hitler’s rampage. They have been enabled by the deception, corruption, coercion and propaganda-amplifying innovations of new technology. The threat of nuclear conflict represents a more overt form of leverage meant to evoke a power hierarchy beyond moral authority.

At the United Nations, where moral authority and those more insidious forms of power have been at odds since the beginning, the General Assembly could get around the veto problem by invoking Article 51, or the responsibility to protect (R2P), or any number of methods that would authorize the use of force if countries had the will to do it, and key alliances such as NATO were prepared to agree to do it. But that remains the key issue. Ironically, the Security Council veto, and the council’s inability to even craft a resolution on humanitarian issues, do not by themselves paralyze the General Assembly. It is the members of the General Assembly that paralyze it.

It is readily apparent that President Putin cares as much about human life, human dignity, personal freedom and the rights of other peoples as did his political predecessor and spiritual ancestor, Josef Stalin. As he has told us, his opponents are but “gnats” to him. The sheer brutality of what he says and what he does reflects that clearly. Just as the West had to come to terms after 1945 with the fact that “Uncle Joe” was a vicious dictator (something naively ignored during the purges and famines of the 1930s), and that the Soviet Union’s views about the nature of the world had to be understood as incompatible with what liberal democracies could possibly stomach, so, too, we now have to face up to what President Putin and his apologists have in the way of war aims.

Putin has told us clearly what he wants. He doesn’t believe in any meaningful independence or sovereignty for his neighbours. He hates the dignity of difference. He wants compliance, he wants control, and he will kill, destroy and lay waste to get that. His first targets are those countries not covered by NATO’s security umbrella, but history has shown that the appetite of tyrants will grow with the eating. He wiped out Grozny with scarcely a peep from anyone, moved on to Georgia, moved into Syria when the red lines evaporated, and maintained a steady attack on Eastern Ukraine, annexing Crimea as his “just reward”.

Putin has clearly miscalculated the resistance and courage of the Ukrainian people and the West’s capacity for solidarity, but he is now so soaked in blood that he will not turn back without inflicting extraordinary damage on the people of Ukraine, and those who are next in line. He apparently does not care about the decision of the International Court of Justice on the measures he has to take to stop committing a genocide. He could care less about the Geneva Conventions, human rights commissions, or any of the myriad institutions steadily built up by the West to protect humanity from unchecked tyranny and punish those who attempt it through the redress of blind justice.

The question for us now is how much do we care about these values and institutions? Four hundred years ago, the French physicist and Catholic theologian Blaise Pascal wrote that “Justice without force is powerless, and force without justice is tyranny.”

We do not have the luxury of impulsive acts that don’t calculate consequences. But enforcement requires political will.

Bob Rae is Canada’s ambassador to the United Nations.