America’s Inflation, Everyone’s Problem

Douglas Porter

February 24, 2023

Last week we opined that the U.S. economic data pointed to higher for longer, and this week the markets said “yep”, with bonds, stocks and currencies selling off. Adding some serious spice to the mix on Friday, January’s core PCE deflator—aka the Fed’s preferred inflation measure—jumped 0.6% m/m and 4.7% y/y. The latter was a full four ticks above expectations, juiced also by upward revisions to earlier months. It actually gets worse when we dig into Chair Powell’s supercore measure (services ex energy and housing), where the 3-month trend popped to an annualized 5.4% clip, flagging no let-up in underlying pressures whatsoever. The core results were notably concerning since they came in above what had already been surprisingly perky CPI and PPI figures.

Financial markets were struggling to digest the recent run of robust U.S. economic data to start the year, even before the PCE deflator added to the discomfort. Ten-year Treasury yields pushed above 3.95% for the first time this year, while 2-year yields flared above 4.8% for the first time since the Global Financial Crisis blew open in 2007. Markets are now fully priced for three more 25 bp rate hikes from the Fed, which would take the terminal rate to 5.25%-to-5.50%. But some are now muttering about even more, with non-trivial odds of fed funds hitting 6% beginning to emerge. Stocks have naturally greeted this development as warmly as a skunk at a picnic, with the S&P 500 retreating for the third week in a row, and now down more than 5% from the early February high.

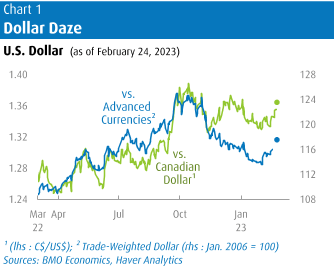

The re-re-pricing on the Fed outlook has given the U.S. dollar yet another charge. After retreating steadily from the 20-year high hit last fall, the greenback has snapped back up since early February lows to reach its highest levels of 2023. For example, the euro has pulled back by more than 4% after nearly touching $1.10 at the start of this month. The yen is also on its back heels again, sagging more than 6% in a month to above ¥136. And the Canadian dollar has certainly not escaped the broader downdraft, weakening below 73.5 cents (or $1.362/US$), down two cents so far this month. In the 15 years prior to the pandemic, the loonie was only weaker for one brief spell—when oil prices crashed below $30 in late 2015.

The Canadian dollar is being undercut by the broader strength of the U.S. dollar, a related risk-off move, but also by some specific home-grown factors. The sudden reassessment of the potential for even more Fed rate hikes follows soon after the Bank of Canada rather publicly planted its flag in the on-pause field. True, the pause was billed as “conditional” on the inflation performance. But just as U.S. inflation surprised to the high side in January, Canada delivered a rare downside surprise in this week’s CPI. Headline inflation cracked below 6% (at 5.9%) for the first time in nearly a year, leaving Canada with one of the lowest inflation rates in the industrialized world. Even Japan’s rate is now not that much lower at 4.3%, and the BoJ is sticking with negative interest rates. Moreover, Canada’s core inflation displayed some encouraging signals, with ex food & energy prices rising only 0.1% m/m in seasonally adjusted terms. That’s the smallest monthly rise in nearly two years, clipping the 3-month trend to a manageable 3.1% (the similar measure in the U.S. was 4.6%).

The Canadian dollar is being undercut by the broader strength of the U.S. dollar, a related risk-off move, but also by some specific home-grown factors. The sudden reassessment of the potential for even more Fed rate hikes follows soon after the Bank of Canada rather publicly planted its flag in the on-pause field. True, the pause was billed as “conditional” on the inflation performance. But just as U.S. inflation surprised to the high side in January, Canada delivered a rare downside surprise in this week’s CPI. Headline inflation cracked below 6% (at 5.9%) for the first time in nearly a year, leaving Canada with one of the lowest inflation rates in the industrialized world. Even Japan’s rate is now not that much lower at 4.3%, and the BoJ is sticking with negative interest rates. Moreover, Canada’s core inflation displayed some encouraging signals, with ex food & energy prices rising only 0.1% m/m in seasonally adjusted terms. That’s the smallest monthly rise in nearly two years, clipping the 3-month trend to a manageable 3.1% (the similar measure in the U.S. was 4.6%).

The not-terrible domestic inflation reading temporarily calmed some of the more aggressive expectations for the Bank of Canada later this year. The blow-out January jobs report, and a run of reasonably good growth figures to start 2023, had convinced markets that the Bank would hike yet again by summer. Those expectations have been revived by the strong U.S. inflation result, as well as by the sagging Canadian dollar.

The main arguments for why the Bank could consider deviating meaningfully from the Fed are two-pronged: 1) Canadian households are much more indebted than their U.S. counterparts, and mortgages are on a shorter cycle than stateside, leaving the economy much more sensitive to higher rates; and 2) wage and price pressures are a bit less intense in Canada. The latest CPI results highlighted some of that gap, and so too did job openings. The job vacancy rate in Canada has dipped below 5% in recent months, while the U.S. rate picked back up to 6.7% in December. And most major measures of wages are running consistently stronger than in Canada.

True, the BoC can deviate a bit from the Fed, but the currency will act as a limiter on the extent of that deviation. That is, the Bank may not have the luxury of staying on the sidelines if the Fed is still busily marching rates down the field, driving the loonie lower (and thereby sending imported costs flaring higher). Import prices were up 13% y/y in Q4, outpacing export prices for the first time in two years. At least some of that import price inflation has been sparked by a 5% drop in the Canadian dollar in the past year.

Alongside recent surprisingly solid growth results, this has prompted the market to again nearly fully price in one additional 25 bp hike from the BoC, pushing GoC yields higher across the curve. The five-year yield—important for the housing market—has vaulted above 3.6%, up by more than 70 bps just since the Bank signalled its pause less than a month ago. While still roughly 25 bps below the extreme peaks reached last October, yields had not previously been in this zone since 2007. Note that, in inflation-adjusted terms, home prices were 40% lower than current levels back then. While we’re not looking for a pullback of that magnitude, it’s safe to say that the back-up in bond yields will put a further chill in a frosty domestic housing market.

The title of this piece is certainly not meant to imply that it’s only the U.S. economy dealing with a serious inflation issue. In fact, European price trends have long since overtaken their American counterparts. The Euro Area’s inflation rate was confirmed at 8.6% in January, down 2 ppts from October’s peak, but now more than 2 ppts north of the U.S. tally. Britain is even loftier at 10.1%. However, a much larger share of Europe’s inflation has been driven by energy costs—even with core CPI hitting a new high of 5.3%, it’s still below the 5.5% U.S. pace. And, the recent melt in natural gas should help cool headline Euro Area CPI aggressively in the months ahead. Gas prices in the Netherlands are now down 60% from a year ago, and back to levels last seen in the summer of 2021. The war in Ukraine is regrettably still grinding on at its one-year anniversary today, but Mother Nature did her part for the right side this winter.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.