An Important Work on Media From a Highly Reliable Source

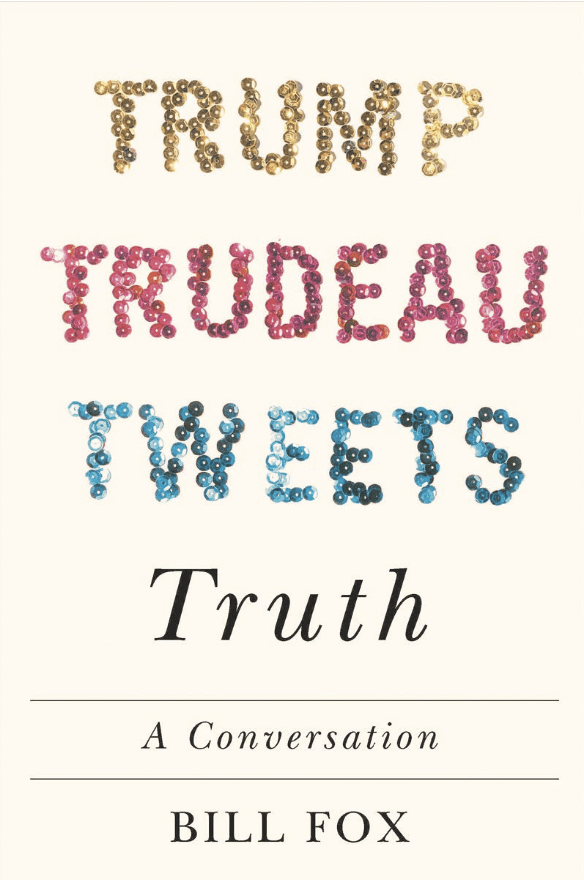

Trump, Trudeau, Tweets, Truth: A Conversation

By Bill Fox

McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022

Review by Anthony Wilson-Smith

For many years, the nexus in Canada between journalism, public policy, politics, big business and communications has had a name: Bill Fox.

By choice, Fox has kept a low public profile for several decades, but his credentials are self-evident: a fluently bilingual Toronto Star journalist turned communications guru to Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, senior executive at three of Canada’s largest companies, consultant to CEOs at many more, author, university lecturer, student at Columbia and Harvard universities, MA and Ph.D and, in 2020, Order of Canada recipient. Dame Moya Greene, the Newfoundland-born former head of Great Britain’s Royal Mail and Canada Post, calls Fox “the very best communications professional. [In any situation] he has that razor sharp mind and nerves of steel.”

Few people are more qualified to dissect the ongoing evolution of global media and communications, and how that affects the country and world in which we live. Add Fox’s blue-collar roots – he still describes his birthplace in the northern Ontario town of Timmins as “home” – and you have someone who can read the collective mindset in almost any situation.

Now, he has done precisely that with his magisterial new book Trump, Trudeau, Tweets, Truth, a carefully-measured mix of analysis, behind-the-scenes history and almost-eerily prescient sense of unfolding events.

While some themes have been explored before, Fox links and explains them in a manner that provides crucial context. In doing so, he builds our understanding of how we got to where we are, and where we are headed, in everything from the way governments function to the day-to-day of how we get along with each other.

The book goes far in explaining how Justin Trudeau managed his unexpected ascent to power in 2015; the rise and resilience of Donald Trump beginning in 2016; the manner in which the COVID pandemic has fed unprecedented distrust in traditional democratic institutions worldwide; and, by theoretical underpinning as to how large-scale protest movements (such as, for example, the “Freedom Convoy”) catch governments so badly off-guard.

The underlying problem, as Fox describes it, is that the world looks one way if you get news through traditional media sources, and quite another from the rough-and-tumble outback of social media influencers and algorithm experts (people who know what trends will torque the number of views they get). The two sides hold different conversations and their exchanges are often garbled, the equivalent of people shouting at each other from different rooms of a house. The first side, shrinking in stature and importance, includes established interests, such as elected politicians, traditional opinion leaders, and the mainstream media.

The second is made up of self-declared outsiders. They range from activists representing minority communities across the spectrum to right-wing and white-nationalist extremists. In North America, unlike much of the rest of the world, they also include monied interests who similarly reject the established order and have the means to act on that.

Those groups variously create powerful communications networks that bypass established media. The result: traditional journalists no longer play the leading role in shaping news of the day. Instead, Fox says, traditional media’s place is ‘increasingly that of a supporting action, a step removed’.

Not so long ago, Fox reminds us, that was not the case. In the early days of the Internet in the late 1990s, it functioned largely as an echo chamber for traditional media. Established news organizations posted articles online, and people reacted accordingly, much as in previous times through letters to the editor. But several things changed dramatically. Traditional media organizations were largely unable to figure out ways to monetize their online presence, and initially treated it as an adjunct of their established business models.

The result was and still is, a shrinking bottom line, and consequently, shrinking newsrooms. Between 2013 and 2018, the number of journalists in Canada fell from 13,000 to barely 10,000 – and precipitous decline has picked up speed since then.

As the number of readers, viewers, listeners – and advertisers – shrunk, the media focused on older, well-educated and affluent consumers who were slower to abandon them. But in doing so, they alienated a large segment of their former audience who didn’t meet that description.

Journalism, a field once populated by high-school graduates working for modest wages, became more high-end and thus more like the people they were covering than the mass audience to whom they had previously appealed. “The professionalization of journalism,” Fox writes, “led to a conversation of insiders.” As media relations increasingly became “an exercise in elite discourse management”, the result was that “the discourse” excluded the general population, because ‘people’ weren’t part of the exercise.’ Moreover, as “the excluded engaged in their own conversations”, those “in the loop were unaware [these] were even taking place.” That, Fox notes, was key to Donald Trump’s rise in 2016: people in traditional circles were so busy talking to each other that they missed the frustration of many people and the consequent groundswell around Trump and his promise to “clear the swamp” of Washington.

That phenomenon of separate, unheard conversations, in different ways, contributed to Justin Trudeau’s unexpected rise in 2015. Like Trump, Fox writes, Trudeau has an innate ability to attract attention. He also had a social media-savvy young team that understood how to use the digital world in a targeted way. His messages on equality, diversity and the environment, among others appealed to young Canadians otherwise less likely to vote.

At the same time, some challenges for journalists have been unavoidable, such as staying timely and relevant with fewer staff and resources. But others, Fox notes, are due to stubborn resistance to changing times and mores. One example is the continuing reliance on “tick-tock” stories that focus on the minutiae of an event rather than its context and consequences. Coupled with that is the continuing importance placed on seeming neutral. That is laudable in theory, but in practice sometimes means established facts and outright lies are reported in a similar tone, just so long as those quotes are delivered by a person in a position of authority.

Donald Trump, for one, understood immediately how he could use what Fox calls the “stenographer component” of traditional journalism – meaning that that what he says “doesn’t have to be truth”. If he says something enough times – such as Trump’s repeatedly-debunked claim that he actually won the 2020 election – a large segment of listeners and supporters accept that as fact.

By the same token, media advisers advise clients – politicians among them – to ignore questions they don’t like and to instead to “treat every question as a message opportunity” to talk about whatever they want.

The now two-year-old global COVID pandemic has, among many consequences, exposed the weakness of the traditional journalism focus on negative news at the expense of more constructive approaches.

As an example, Fox cites the introduction of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), by which the federal government provided immediate financial support for millions of Canadians who faced financial disaster at the onset of the pandemic. Within days, the government rolled out a program by which those who qualified could apply for benefits at the start of a week and have a cheque in hand before that same week was over. That was by almost any measure a remarkable achievement– yet media coverage focused on occasional instances of abuse or delay. That approach fed distrust of traditional institutions – which, by extension, includes the media.

Some solutions to all this, Fox suggests, are straightforward. One is a step the federal government is already considering – a tax on social media giants like Facebook and Twitter that profit from using traditional media content without appropriate compensation.

Transferring those monies to make up for lost revenue would allow media organizations to rebuild their newsrooms – and relevance. (Some journalists reject any financial support of this nature on the grounds that it makes them appear beholden to government.)

Fox also suggests an attitude check for editors and reporters on the way they assign and report stories. They need to report on more voices from people who aren’t traditional newsmakers, step away more often from news conferences with manufactured messaging, and recognize that just because they have always approached their craft a certain way isn’t good enough reason for continuing to do so.

That need to change comes with a reminder that we have always relied on the perceptions of others in forming our vision of the world. In 1922, Fox notes, the great American journalist Walter Lippman wrote: “What each man does is based not on direct and certain knowledge, but by pictures made by himself, or given to him.” And, as Canada’s own media guru Marshall McLuhan said in 1964, “any new means of moving information will alter any power structure whatever.” Fifty-eight years later, the challenge to those structures is clear and ongoing.

Thanks to this important book, we better understand the reasons why, the effects of those changes – and some needed steps to knit our disconnected worlds back together.

Contributing Writer Anthony Wilson-Smith, former Editor-in-Chief of Maclean’s, is President and CEO of Historica Canada.