Anatomy of a Fiscal Fiasco: How a UK Mini-Budget Brought Down its Architects

Kevin Page, Nabila Antora and Matthew Mcgoey

October 27, 2022

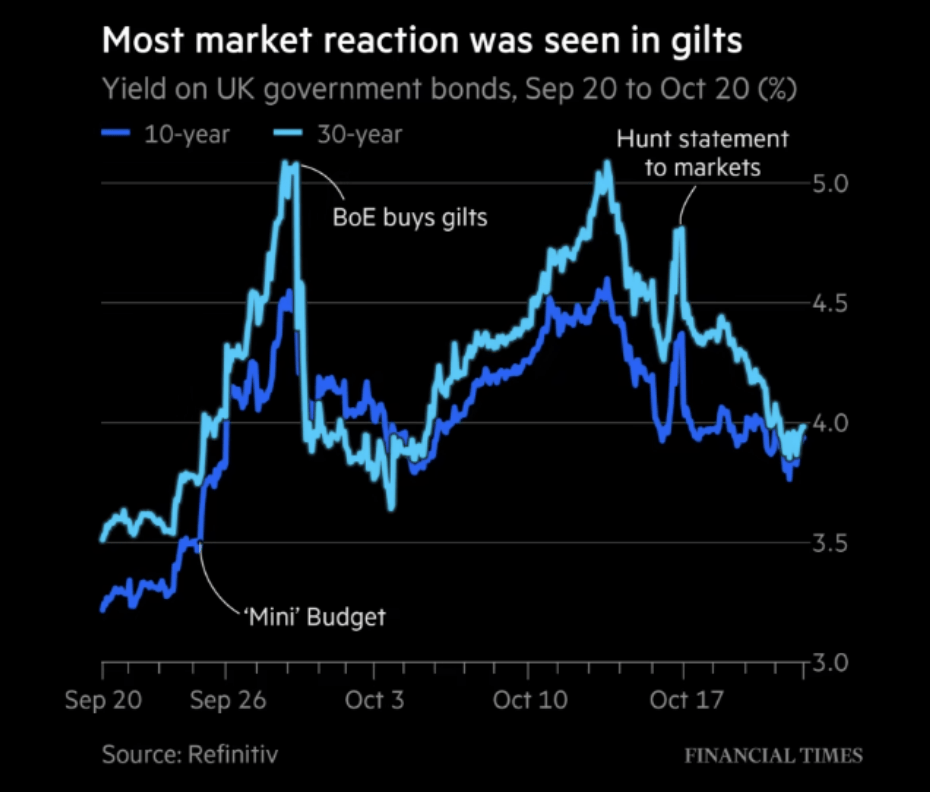

On September 23, then-UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Kwasi Kwarteng presented a mini-budget dubbed The Growth Plan. Within a month, that mini-budget had unleashed a major political crisis — including the resignations first of Chancellor Kwarteng, then of Prime Minister Liz Truss — as well as significant financial turbulence in both the currency and gilt markets. On October 17th, Kwarteng’s successor, Jeremy Hunt, announced remedial measures to repair the damage from the mini-budget. Hunt, who has remained chancellor under Truss’s successor, Rishi Sunak, is set to deliver a new budget statement on November 17th.

The word fiasco is defined as “a complete failure, especially in a ludicrous or humiliating way.” By all accounts, the UK mini-budget was a fiasco.

There is a wide body of important research around the general theme “anatomy of a crisis”. It is likely that in the near future, the mini-budget fiasco will be an additional case study. The research on crises highlights common stages and elements.

The four common stages of are characterized as (1) pre-crisis, (2) crisis, (3) clean-up, and (4) post-crisis.

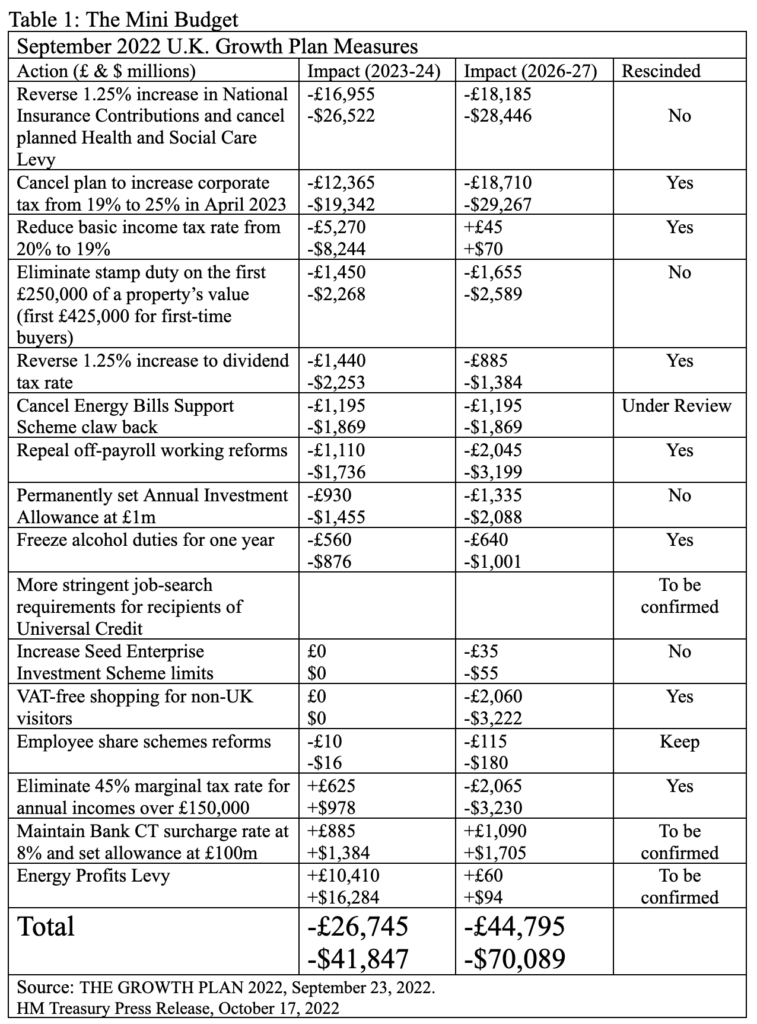

In this vernacular, the UK is currently in clean-up mode. A new economic and fiscal direction has been unveiled by Chancellor Hunt that puts a premium on economic stability and fiscal sustainability. Specific mini-budget measures have been formally rescinded (Table 1).

Gilt and currency markets have stabilized to near pre-crisis numbers. The clean-up will continue with the tabling of a new budget statement on November 17, 2022. Given the multiple dimensions of the crisis, the post-crisis period could be many months away. Confidence and trust will need bolstering.

Research by William Ury and Richard Smoke (Anatomy of a Crisis, 1991) highlight four common elements.

First, crisis stakes are high and get raised unintentionally by a failure to grasp broader consequences. A newly minted Prime Minister Truss and Chancellor Kwarteng rushed to deliver a growth agenda that did not fit economic circumstances: high inflation; relatively large but declining fiscal deficits; and high economic uncertainty. The tax reduction package was historically large (Table 1) and was to be deficit financed in a high inflation environment. High political stakes collided with the wrong economic prescription for the times.

Second, in crises, the time for deliberation is often limited. In the mini-budget fiasco, there was no pre-budget consultation. No second opinions from experts. There was no economic and fiscal medium planning framework provided by the independent Office of Budget Responsibility tied to the UK Treasury. The prime minister and chancellor delivered a take-it-or-leave-it scenario. They were forced to leave by the loss of financial and political confidence. It was a self-inflicted error of both judgment and policy.

Third, crises are compounded by high uncertainty. Good information to support strategy and decision making is essential in current times with the world facing serious multiple economic, environmental and political challenges. The information supporting tax cuts to generate economic growth is based more on ideology than sound economics. While monetary policy authorities around the world are raising interest rates to address high inflation, the logic of deficit- financing tax cuts to spur demand and growth (the largely discredited, Reagan-era approach of “trickle-down” economics) was considered unsound by financial markets and international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Fourth, crises often evolve within a framework of narrow, polarized and extreme options. The mini-budget had a narrow focus — economic growth funded through deficit-financed tax reductions. Chancellor Hunt is already working to broaden the policy strategy and economic narrative to highlight stability and fiscal sustainability in times of high uncertainty.

Are there lessons to be learned for Canada in the UK mini budget fiasco?

It is fair to say that we have no modern comparable Canadian budget experience where financial markets, opinion makers and legislators so dramatically mobilized against a government budget strategy, resulting in political resignations and policy reversals. Still, we have had some strategic misfires.

In the fall of 2008, the Conservative government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Finance Minister Jim Flaherty released a fiscal update that significantly misjudged the economic environment – the 2008 global financial crisis. In a minority parliament scenario, Parliament was shut down and the government quickly returned with a budget with significant fiscal stimulus.

In the fall of 1981, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Finance Minister Allan MacEachen tabled a large budget that proposed spending restraint and the closing of tax expenditures (denoted as loopholes) in a high-inflation, high-deficit and recessionary environment. Many of the proposed tax changes were deemed unpopular and were rescinded. Political and public support was needed to tackle stagflation and high government deficits.

Reflecting on the UK mini-budget experience, perhaps the best advice has come from former Bank of Canada and Bank of England Governor Mark Carney in his statements at both the recent IMF meetings in Washington D.C. and in our Senate meetings on the state of the Canadian economy and inflation. Carney is advocating fiscal discipline. Budget deficits need to be reduced through the unwinding of COVID-related fiscal supports. As he noted, financial markets will punish bad policy. Fiscal and monetary policy must be aligned to reduce high inflation and promote global economic stability.

Next up is the Fall 2022 Federal Economic and Fiscal Update expected in November. Financial markets will be watching.

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, former Parliamentary Budget Officer and a contributing writer for Policy Magazine.

Nabila Antora and Matthew Mcgoey are undergraduate economics students at the University of Ottawa.