Assessing the Impact of Canada’s Feminist Foreign Assistance

Caroline Wilson

February 14, 2023

Canada has earned a reputation for being a serious player when it comes to applying a feminist lens to its foreign policy.

Recently, the Canadian government announced its commitment to funding $100 million in Feminist International Assistance Policy (FIAP) to support the Indo-Pacific. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau also reemphasized Canada’s commitment to gender equality and women’s empowerment in his latest meeting with President Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico at the North American Leaders Summit.

The Canadian government has made a significant shift in the right direction, but how the policy works out in practice needs to be justified in the program monitoring and evaluation phases. A feminist lens to foreign policy is not just about representation, but also about the agency and equity that ensures a transformative approach to current challenges.

In the five years since FIAP was adopted, how much of an impact has Canada actually created at the ground level? It is important to evaluate those efforts going forward in order to meet targets efficiently.

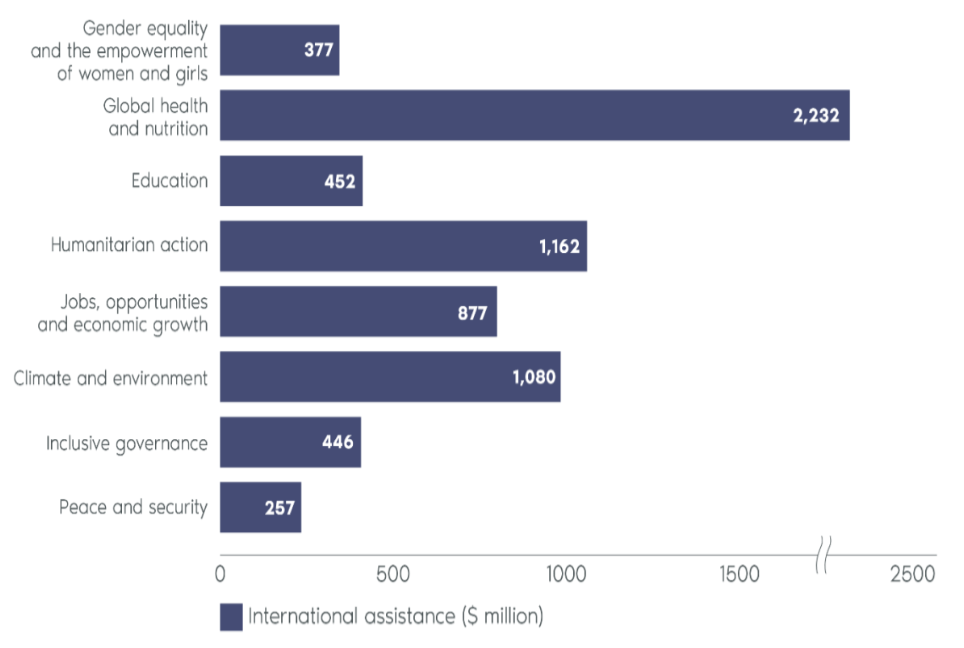

The FIAP was launched by the liberal government in 2017 as a move to reduce poverty and gender inequality across the globe. It is based on the six thematic areas of the U.N. Agenda 2030 with a focus on: Gender Equality and Empowerment; Human Dignity; Growth for Everybody; Environment and Climate Change; Inclusive Growth; and Peace and Security. FIAP argues that the feminist approach to international development through the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls can lead to the transformation of social norms and power relations. It seeks to eradicate poverty and build a more peaceful, inclusive, and prosperous world.

The story so far:

The government directed 95 percent of its bilateral international development assistance towards gender equality projects in 2021-2022, which were delivered through twenty federal organizations in eight core areas. Within the inclusive gender equality projects, $150 million over five years was provided for Women’s Voice and Leadership, and $300 million was dedicated to the 15-year Equality Fund initiative to strengthen women’s organizations and movements, especially in conflict-affected countries.

Under various programs, several women’s organizations and networks were enlisted to prevent, respond to and end sexual/gender-based violence. Some of the initiatives included incorporating data analysis tools for gender equality in the Middle East, countering discrimination and violence against people with disabilities in Haiti, and advocating for women’s health in Ukraine, among others.

Canada’s efforts are commendable and FIAP’s broader framework can be an effective example for international assistance and development. However, if one looks closely, there is a lack of transparency on how effectively the funds are used on the ground. The role of the government does not end at merely sponsoring programs and providing assistance if the aim is to create transformative change for empowerment and poverty reduction.

The FIAP by definition has been collaborative and inclusive, but there is not enough transparency on how it aims to create structural transformation like its Swedish counterparts.

Aid effectiveness increases when donors use a country systems model — a framework whereby a country’s own institutions and systems are used to assess foreign aid effectiveness. Currently, the system is not flexible enough to allow context-specific programs. For instance, per Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reports cited by Global Affairs Canada in its June 2020 evaluation of international assistance programming in Afghanistan, Canada’s assistance in Afghanistan was influenced by donor priorities at the expense of fully representing the Afghan population’s unique, complex, and evolving situation.

Results-based assessments are not enough to capture changes in structural inequalities and hierarchical power dynamics. One of the most important ways of accessing the performance of assistance is by taking feedback from aid recipients to evaluate the support they have received. The government currently uses participatory methods and in-depth contact with stakeholders however, there is a lack of clarity on how the exactly the feedback is being put to use.

Furthermore, there is a lack of transparency in the process of how recipients are selected. This information largely remains within state channels, and the lack of accessibility to the general public prevents individual donors from making a fully informed decision for donations.

The government of Canada has done a remarkable job when it comes to international aid but there is a need for increased transparency in impact assessment on contributions. International aid should not be used as a mere instrumental tool for existing organizations and movements but as a transformative instrument that challenges systemic power imbalances and promotes equity and empowerment, starting at the local level.

Caroline Wilson is a master’s student at the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. She holds a master’s degree in Development Studies and a bachelor of arts degree in sociology. Caroline has previously worked with the Government of India on women empowerment projects and on collaborative education programs in India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.