Bracing for Impact

Douglas Porter

September 23, 2022

The risk of a North American recession over the next year has now climbed above 50%. Accordingly, we are adjusting our forecast to reflect a moderate downturn in the first half of 2023 in both the U.S. and Canadian economies. We previously had one negative quarter built in, signalling the relatively high downside risks to the economy from soaring inflation and the need for aggressive rate hikes. Those risks have simply been amped up by the persistence of underlying inflation—particularly in the U.S.—and by the rising possibility of a monetary overshoot. Geopolitical concerns are adding an unwanted ingredient to the noxious mix (President Biden’s comments on Taiwan, and Putin’s latest rattling of the nuclear sabres). Financial markets are now fully absorbing the Fed’s harsh message that there will be no retreat from the inflation fight; the steep back-up in global rates further bludgeoned stocks, resource prices, and commodity currencies this week given mounting recession odds.

Amid this week’s swirling series of events, the FOMC’s 75 bp rate hike may have been the least surprising element. The accompanying statement changed as few words as possible from the prior effort, all but locking in yet another 75 bp hike in November. Alongside an aggressive upward revision in the dot plot and Chair Powell’s unwavering message, we have further cranked up our expectation on additional Fed rate hikes. Bluntly, it makes little sense to veer far from the Fed’s stated expectations at this time, since it appears policymakers have strapped on the blinders and will keep at it until inflation has convincingly cracked. And that will still take some time yet. Accordingly, we are now expecting a 75 bp hike in November, 50 bps in December, and 25 bps at the first meeting in 2023, taking the funds rate to a peak of 4.50%-to-4.75% early next year, a net addition of 25 bps at each one of those three meetings. And then we expect that rate to hold through 2023.

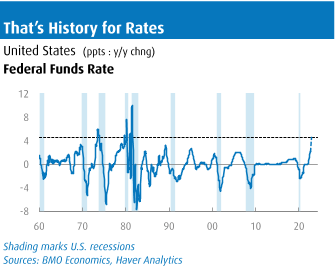

In turn, this more aggressive series of rate hikes will weigh more heavily on the U.S. economy. After all, we are now looking at a cumulative 450 basis points of tightening (with 300 bps already in the bag) in the short space of under a year. (Note that at the FOMC meeting just one year ago, the Fed was only talking about the possibility of beginning to taper QE.) The only other periods when the Fed has hiked rates that rapidly in the post-war era were in 1973, 1980, and 1981, and all three episodes ended in recession. An old rule of thumb is that every 100 bps of hikes could clip real GDP growth by up to 1 percentage point over a year. The extra 75 bps of Fed tightening we are now assuming will cut growth next year by roughly half a point to zero, with outright declines in the first two quarters.

Bluntly, it makes little sense to veer far from the Fed’s stated expectations at this time, since it appears policymakers have strapped on the blinders and will keep at it until inflation has convincingly cracked.

The darkening growth outlook, and a further sag in oil prices this week to below $80, did little to halt the relentless back-up in global yields. A wave of hefty central bank hikes, including a surprise 100 bp move by Sweden and a 75 bp response in Switzerland, and the promise of more, drove long-term yields sharply higher almost around the world. The U.K. by far saw the steepest climb, with 10-year Gilts soaring more than 60 bps to above 3.75%, even as the BoE mildly surprised on the low side with a 50 bp hike. In a stark warning to policymakers everywhere, U.K. yields especially surged on Friday’s fiscal easing, which included tax cuts of around 2% of GDP, while the pound was crunched by more than 3%. U.S. 10-year Treasury yields punched up about 22 bps on the week to around 3.7%, nearly keeping pace with the 30 bp rise in 2s to around 4.2%. In line with the bumped-up Fed call, we are also lifting our near-term assumption on 10-year yields, with a test of the 4% level likely by year-end.

This unfortunate series of events has also prompted us to downgrade our Canadian growth outlook. Similar to the U.S. forecast, we are now expecting GDP to decline in the first two quarters of 2023, carving annual growth to zero (from 1.0% previously). While our call on Bank of Canada rate hikes has only been nudged up by 25 bps (to a 4.0% peak rate), much weaker U.S. activity, and the ongoing slide in oil and other commodity prices will all weigh heavily next year. Amid the many other revisions to our call, we are also trimming our WTI oil price assumption by $5/bbl this year and next to an average of $95 and $90.

The pullback in oil and gasoline has already helped take Canadian inflation off the boil, with this week’s August CPI report surprising to the low side at 7.0% (down from June’s 8.1% peak). The relatively mild CPI, including an encouraging downtick in the core measures, helped Canadian bond markets massively outperform. To wit, 10-year GoC yields actually dipped 7 bps to below 3.1% even as 10-year Treasuries were zooming above 3.7%. Proving that no good deed goes unpunished, the Canadian dollar has since been taken to the woodshed, in part on the view that the BoC will lag well behind the Fed on further rate hikes. After sagging almost 2% last week, the loonie fell by a similar tally this week to below 74 cents (or above $1.357/US$).

Until recently, the modest decline in the Canadian dollar has been almost entirely a story of a rollicking U.S. dollar. However, the latest setback is more loonie-specific, amid sharply widening U.S.-Canada rate differentials and sagging energy prices. (No need to mention that the loonie saw precisely no lift from soaring energy prices earlier this year, but is now being fully caught in the downdraft.) Currencies have a long and storied history of overshooting, and we suspect the loonie is at risk of a more intense short-term sell-off. A test of the 71-cent level (i.e., $1.40/US$) is certainly a risk in the weeks ahead. Digression: As economists, we can only shake our heads in wonder that relatively low inflation is somehow bad news for a currency; by that twisted logic, the Argentine peso and Turkish lira should be on fire. Ultimately, we expect the U.S. dollar to lose some of its formidable steam around the turn of the year as the end of Fed hikes comes into view. And, we thus expect the Canadian dollar to gradually recover in 2023, albeit ending next year lower than we previously expected at around 77 cents ($1.30).

The lone currency that managed to hold its own in this tumultuous week was the Japanese yen, which ended almost unchanged on net at ¥143. But that “stability” was only due to the first currency intervention by Japan since 1998. Arriving on the 37th anniversary of the Plaza Accord—which was aimed at reining in a runaway U.S. dollar—the intervention also sought to slow the yen’s rapid descent. The sagging currency has boosted Japan’s inflation rate to 3.0%. While that pales in comparison to the rest of the OECD, that’s a high rate for Japan, where inflation averaged almost nil in the previous 30 years. Yet, the BoJ remains steadfast in its lack of appetite for rate hikes, leaving the yen entirely exposed to further downward pressure. More broadly, the U.S. dollar steamroller grinds on with the Fed on the warpath, and apparently not unhappy with the inflation dampening impact of a strong currency.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.