Brian Mulroney: A Canadian Life

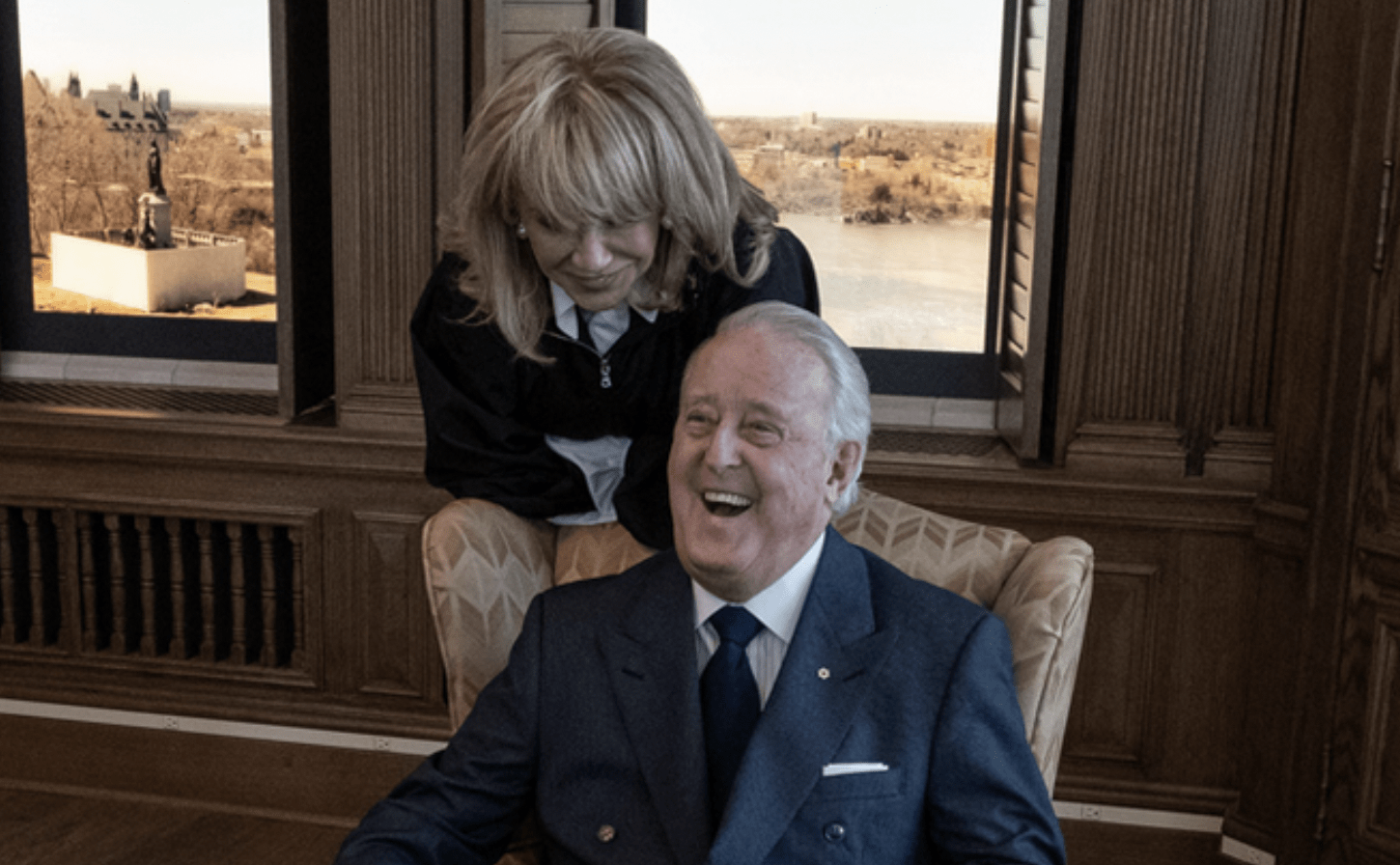

Brian and Mila Mulroney at the Mulroney Institute/Brian Mulroney Institute of Government

Brian and Mila Mulroney at the Mulroney Institute/Brian Mulroney Institute of Government

By Charles McMillan

March 22, 2024

On February 29, 2024, a leap year, Canada saw the passing of its 18th prime minister. Martin Brian Mulroney lived life to the full, adored his wife, closest friend and confidante, Mila, and cherished their four children.

He was born in Baie Comeau, on the North Shore of the mighty St. Lawrence River, and like many young boys across Canada, Brian’s interests were simple: hockey, girls, fishing, and his close family. His father, Benedict, worked as an electrician in the local pulp and paper mill, which provided the paper for Col. Robert McCormick’s Chicago Tribune. His father died too early, so the future leader had to assume family responsibilities early in his teenage years.

Long before he became active in politics, what made his real persona had little to do with political life. In this feature, he stands unique among federal political leaders, who often spent years in opposition before winning office – Laurier, Borden, King, Diefenbaker, Clark, Campbell, for instance.

Growing up in a town perched above one of the world’s great trade arteries whose economy depended on one of the world’s major newspapers, and his high school years boarding away in Chatham, N.B., gave him a wider worldview at an early age.

His boyhood friends were francophone, anglophone, Cree, and he spoke English and French effortlessly, knowing only too well how to swear like a sailor in both official languages. As a teenager, he became a keen listener to CBC/Radio Canada, an institution that, through radio and later television, opened up new vistas, voices, and opinions across Canada and the world. Like many youthful Junior B quality hockey players, he was an early and lasting supporter on the Montreal Canadiens, and Saturday and Sunday night were focused on games at the Forum, with Dany Gallivan calling the play, or away games on Sunday, with René Lecavelier in French.

His first real practical education came from leaving his boyhood home for a year of high school in New Brunswick, and then St. Francis Xavier university. At St. F. X., in Antigonish, he cultivated new friendships, including his new roommate, Sam Wakin, a student from Saint John of Lebanese heritage. Undergraduate studies were important, but other activities took priority, including sports, debating, and drinking beer with his classmates.

Brian soon learned they came from different regions of the country, had different ambitions, and had their own opinions, religious convictions, and political party affiliations. He also soon learned what he didn’t know, and that was reinforced in the classroom by sympathetic professors.

After graduation from St. F.X., and his admittance to the law school at Laval, he met classmates who took law seriously: Peter White, Michel Cogger, Lucien Bouchard, and Bernard Roy. They formed a tight-knit group of smart, ambitious rising stars.

As a practicing labour lawyer in Montreal, he quickly experienced a new, practical side of his education with strike action at the Port of Montreal and later at Quebec’s leading newspaper, La Presse. He never played the blame game. He spent time with the workers and union leaders during the strikes, and soon learned the union members’ plight, and used his Irish charm to help reach a settlement, making sure each side came out winners.

In the 1970s, Canada ranked high internationally on days lost due to strikes, and in Quebec, the same contentious issues were in action, including in the construction industries. Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa set up a commission to study labour and trade union issues, chaired by Judge Robert Cliche. Mulroney was a natural choice, as was his old classmate and friend, Lucien Bouchard, to serve as legal counsel. It made the early names and reputations of both young lawyers.

On the campaign trail in 1988/Bill McCarthy

Mulroney ran for the Tory leadership, using the Cliche Commission experience and building a Tory base in Quebec as his platform. Joe Clark won, but Mulroney had caught the political virus. He returned to his law practice but received an offer to become executive vice-president of the Iron Ore Company. By 1978, he was president, and became an expert on competitiveness for an entire sector of Canadian industry, and by extension earned a de facto PhD in the country’s economy.

The 1979 fall of the Clark government on a budget measure, and Pierre Trudeau’s return to power in February 1980, is a tale from a Hollywood movie. Mulroney took a very different approach to the 1983 leadership contest, largely concentrating only on the 3300 voting delegates, and telling all his supporters to obey the 11thcommandment, “Never speak ill of another Conservative”. When he won the leadership in June 1983, he focused on caucus unity, including the candidates who opposed him, and began the slow process to rebuild the party riding by riding.

For Brian, the goal was a big-tent party, not an ideological club with exclusionary boundaries. That meant recruiting staff, candidates, and supporters from a diverse talent pool across Canada, and building a secure political party base in Quebec and French Canadians living outside Quebec.

From the late hours on the Saturday night when he assumed the leadership to the nine years he served as prime minister, he put little faith in wishful thinking, the role of luck, or the weaknesses of the opposition. He worked hard, played hard, and nurtured his support in the caucus and among party members.

His business experience and international network revealed a changing world order, the new role of Asia, and new centers of financial strength. He always felt that to compete on the world stage, you had to have a strong domestic economy. His new government inherited huge deficits and debt, and many sectors both in Canada and the US had lost their competitive edge, the auto sector being a prime example.

He campaigned on national unity and better relations with the US, but knew the mood in Congress and much of the American private sector had become deeply protectionist. Yet Canada belonged to NATO, was a key member of the Commonwealth, and he wanted to strengthen relations with France and the Francophonie.

Overall, for him, some of the key initiatives would come with help from the leaders in the G-7 and NATO. Politically, the government had to deal with multiple files at once, each with different timelines, and many drained the government’s political capital. The work pace was relentless, but he constantly cultivated support in his caucus and cabinet. A fact unappreciated by many of his campaign advisors, he enjoyed meeting the voters directly, and in his 1988 re-election bid, he actually sat down after a rally to meet with some fierce hecklers.

Mulroney’s political legacy will be left to history, but his many awards, tributes, and policy direction — once scorned and derided and now accepted as necessary — illustrate the nature of the political system. As leader and prime minister, he brought key skills to the job – great listening skills, a capacity to reach experts, and saw politics as the ultimate team sport. As Senator Hugh Segal once remarked, many in the public sphere labeling Mulroney as a right-winger ignored the fact that he “wore his social conscience on his sleeve.” May he rest in peace.

Charles McMillan, Professor of Strategy at the Schulich School of Business, is the author of The Age of Consequence: The ordeals of Public Policy in Canada -1968-2018. He served as senior policy advisor to Brian Mulroney from 1983-1987.