British Columbia May Hold the Balance of Power

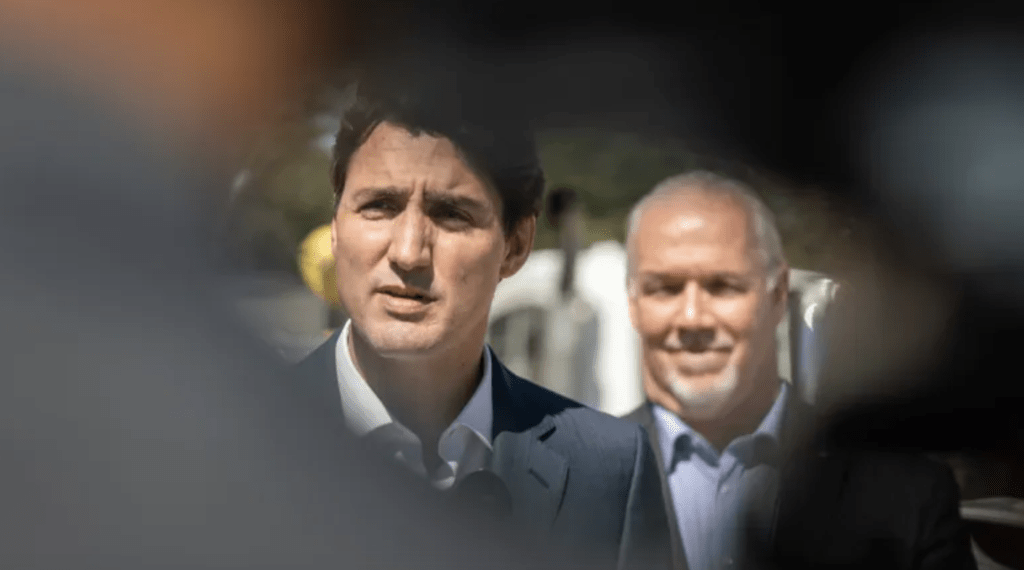

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and NDP BC Premier John Horgan/Photo by Maggie MacPherson, CBC.ca

Robin V. Sears

September 15, 2021

For two decades, it has been a cliché that the voters of suburban Toronto have a unique hold on who will form government for the rest of Canadians. It’s true that the GTA voters have been fickle, flipping between Liberals and Tories several times. But Quebec has been more punishing to each of the major parties in sequence far more heavily, for five elections in a row.

It is perhaps a function of the Central Canadian bias of the national media that little attention is ever paid to British Columbia and even less to Atlantic Canada. But in this election, BC may once again demonstrate its ability to confound election forecasters — and show who the real kingmaker is.

BC has 42 seats in the 338-member House of Commons. One week before election day, the CBC Poll Tracker average shows the Conservatives at 30.5 percent, the Liberals at 27.9 and the NDP at 28.0. In an election returning a minority House, BC could be holding a lot of cards.

BC has a history of confounding federal election forecasters. In 1972, shortly after the election of the first NDP government in the province, BC returned 11 NDP MPs to Ottawa, making up one third of the caucus and giving David Lewis the balance of power in the second Pierre Trudeau government. The Liberals held only 109 seats to 107 Conservatives in a precarious minority House. It led to a very productive two-year partnership, producing Petro-Canada and the first Election Expenses Act, among other progressive changes.

In 1979, BC held overlapping provincial and federal elections with surprises in each. The Liberal and Conservative parties were virtually wiped out by Social Credit provincially. The five Liberals elected were swallowed up by Social Credit or retired before the next round. In the federal election held only 12 days later on May 22, there were further upsets. The Tories almost swept the province, electing 19 MPs, leaving eight for the NDP and only one Liberal. The result contributed to another minority government — but Joe Clark’s was an historical blip, leaving no legislative legacy and lasting only nine months.

This year is looking like another “BC surprise”, with both the NDP and Tories climbing at the expense of the Liberals. At dissolution, the Tories led with 17 of BC’s 42 seats, with the NDP and Liberals at 11 each and the Greens with two. Local strategists say there are probably six Liberal seats at risk, with former Justice minister-turned Independent MP Jody Wilson-Raybould’s seat also up for grabs. In her old riding of Vancouver Granville, the Liberal candidate is a confessed house flipper with dozens of flips and millions of dollars earned — not a likely resumé for victory in the most affordable-housing challenged city in the country. The NDP seem likely to pick up at least one of the two Green seats in the province, as a result of the bitter civil war in that party. The other is former Green Party Leader Elizabeth May’s, still considered safe for her at this writing.

A recent EKOS poll showed the Mad Max circus—Maxime Bernier’s People’s Party of Canada at six percent in the province. This is probably higher than the actual votes it will receive next week, but it is not surprising.

As in 1972, the province is governed by a very popular premier, John Horgan, and an NDP government with a large majority. Although Horgan and Justin Trudeau have had an entente cordiale since Horgan’s election, rarely jousting in public and hammering out several very important deals for the province, elections change everything. In 2019, Horgan waited until the final hours of the campaign to stump for and endorse Jagmeet Singh. Nonetheless, a thin-skinned prime minister, and his hyper-partisan inner circle went ballistic, according to a senior NDP source, yelling and making threats on the phone. Given Trudeau’s relative unpopularity in BC, Horgan has even less reason for restraint this time.

A recent EKOS poll showed the Mad Max circus—Maxime Bernier’s People’s Party of Canada at six percent in the province. This is probably higher than the actual votes it will receive next week, but it is not surprising. BC is unlike like Alberta in almost every political sense, closer in values to Ontario or Quebec than its western neighbours on climate, COVID vaccination mandates, child care and pharmacare. But the strength of the PPC in BC shares roots with northern and eastern Ontario. High unemployment, battered small cities, deep anxieties about the decline of the forestry and mining sectors, and COVID fatigue.

Interior and Northern BC are as different from Vancouver and the Island in culture, values and concerns, as Toronto is from Kenora. The PPC strength there, if it holds, will probably will hurt Erin O’Toole the hardest, but the NDP and Liberals will not be unscathed. Like Obama/Trump voters in 2008 and 2016, the disgruntled populist message may appeal to frustrated NDP forest workers and some 2015 first-time Trudeau voters now furious at the devastation that fire, economic decline, and the pandemic have done to their lives.

Across Canada, Jagmeet Singh has pulled up support among first-time voters and the 18-34 generation to previously unheard-of levels — nearly a third of voters in most polls. It is even higher in BC. The frustration for New Democrats is that the turnout numbers in that cohort are usually weak. Local NDP campaign managers, however, report that the walk-in numbers of young voters asking how they can help has never been higher. So, perhaps this year will be different and younger voters will turn out in greater numbers than usual.

Asked to reflect on what he saw was different in the fall of this year, as opposed to two years ago, one veteran NDP strategist and former MP saw two big changes. The BC Indigenous community, and their allies, were deeply offended by Trudeau’s failure to meet even the most basic of tests on his reconciliation agenda. They were also troubled by the revival of Jody Wilson-Raybould’s tale of how badly she was treated and her claim, denied by Trudeau, that he had asked her to lie about the SNC-Lavalin affair.

Secondly, he observed that BC voters were among those Canadians who fell the hardest for the “Sunny Ways” Trudeau of 2015. By 2019 some of the shine had come off, but not entirely. This time, he said, “the Teflon has been entirely scraped from the pan.” There is a deep disappointment, even disdain for this year’s Trudeau.

If 2021 in BC were a repeat of either 1972 or 1979, with strong NDP and Tory contingents from the province at the expense of the Liberals, it would contribute mightily to a cap on Liberal hopes nationally, leaving them with another minority government at best. And BC would once again demonstrate that sometimes it determines who goes to Ottawa as prime minister.

Contributing Writer Robin V. Sears, former national director of the NDP during the Broadbent years, was visiting friends and former colleagues in BC last week. He is an independent communications consultant based in Ottawa.