Budget 2023: Will the Government Stay the Course on Deficit Reduction?

Kevin Page with Alex Eikre and Zhihan Li

March 21, 2023

On Tuesday, March 28th, Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland will table Budget 2023 in the House of Commons.

Since taking the Finance reins in 2020, Freeland has successfully steered public finances towards normalcy. The federal budgetary deficit has fallen from a COVID-related record high of $328 billion in 2020-21 (14.9 percent of GDP) to an estimated $36 billion in 2022-23 (1.3 percent of GDP). It is a dramatic decline.

Is this the end for deficit reduction or can the government deliver on its 2022 Fall Economic Statement fiscal update to move gradually towards a balanced budget over the next three to four years?

Maintaining modest planned budgetary deficits will provide the government the fiscal room to deficit finance a number of initiatives on its priority list – health care, green subsidies, further supports for vulnerable people to combat inflation, defence spending and Ukraine. On the other hand, maintaining fiscal consolidation will help rebuild fiscal buffers for the next crisis and support the Bank of Canada commitment to reduce the rate of inflation to the 2 percent range over the next year. Budget 2023 will tell us what policy path the government is on.

Under Westminster parliamentary traditions, budgets play an important and pivotal role in the financial cycle. They provide an assessment of the standing of the nation’s finances, the economic condition of the country, and the fiscal plan to finance the policies of the government. The budget links consultation with citizens and stakeholders on policy issues to the legislation and audit phases of the cycle.

We need a good budget debate on strategy, priorities and policies to address short-term instability risks and long-term transition challenges.

Partisan debate is to be expected. Budgets are political documents. We have a minority House, though the traditional risk to the government based on a post-budget vote of non-confidence is all-but neutralized by the Liberal-NDP supply and confidence agreement reached a year ago.

The Canadian economy is slowing down in response to significant monetary tightening over the past year. Whether there will be a soft landing (weak growth) or a hard landing (a recession) remains an open question and a planning challenge for Budget 2023.

Trade-offs are also to be expected. Resources are constrained, particularly in a high inflation and high public debt environment. Given the potential downside risks relative to monetary policy tightening and the Russia invasion of Ukraine, a cautious fiscal strategy would favour a slimmer budget. Freeland herself has telegraphed that this budget will land in a context of “fiscal restraint” and “challenging choices” — a pre-calibration of expectations directed at both the public and the markets.

Chances for steering the best policy path ahead are enhanced with good ideas from across political parties, compromise and a willingness to work together. Now is a good time to build trust and confidence in our institutions. Let the debates begin.

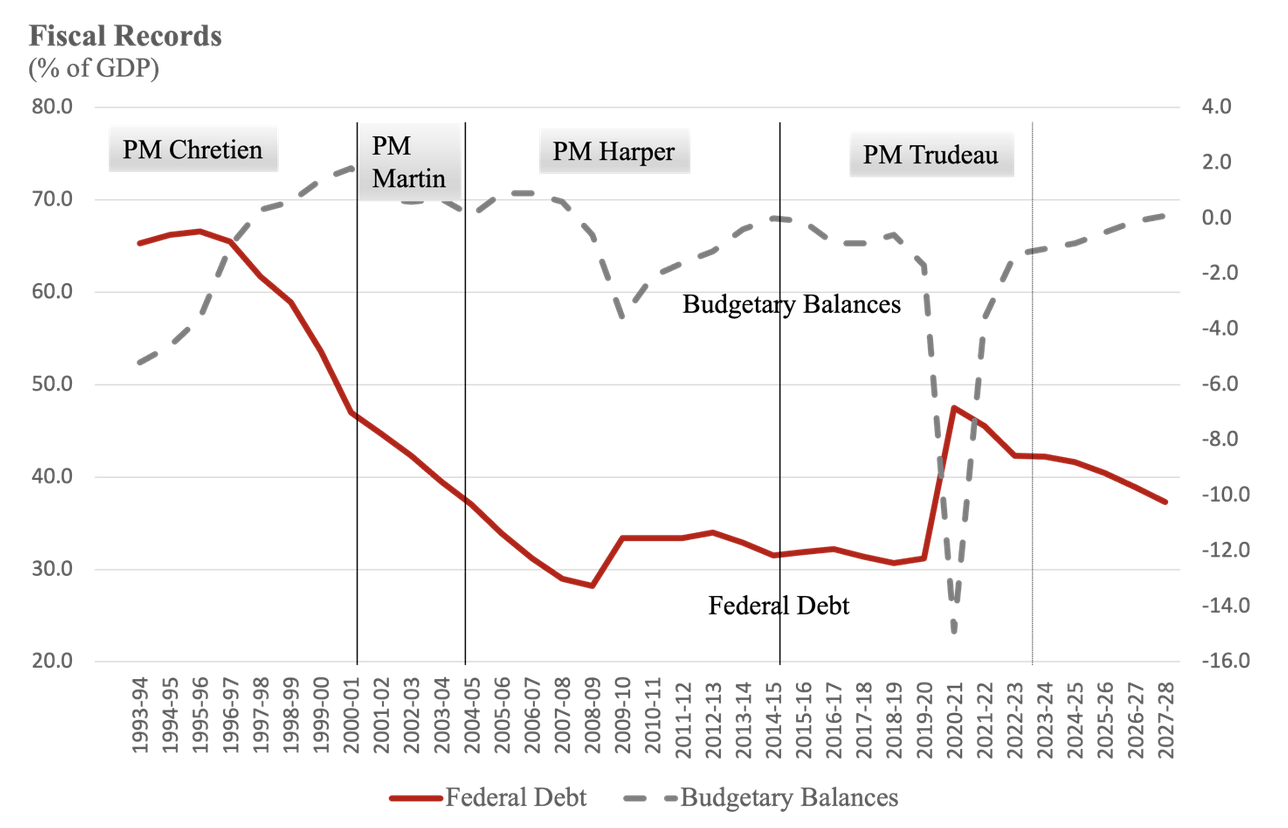

The nation’s finances were severely battered by the COVID public health crisis and related fiscal supports (Chart 1). The federal debt as a percentage of GDP went from 31 percent to 48 percent in one year. It is a level of debt we have not seen in more than 20 years, when high federal debt was considered a major policy issue. With rising interest rates, higher public debt charges can eat up valuable fiscal room to maneuver.

Chart 1

The nation’s finances have weathered the storm. The debt-to-GDP ratio is falling on a relatively steep path and could be below 40 percent within the next five years. A strong economic recovery and the unwinding of COVID supports have been the key success ingredient thus far. The fiscal turnaround was essential to maintain Canada’s triple A (investment grade) debt rating. Finance Ministers around the OECD would welcome Canada’s numbers on deficits and debt.

Budget 2023 will be the seventh budget of the Liberal Government (no budget was tabled during the COVID crisis in 2020). The government’s fiscal legacy is on the line.

Prime Ministers Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin will long be remembered for positively turning around Canada’s fiscal standing. They have Hall of Fame status. They created the fiscal buffers that allowed prime ministers Stephen Harper and Justin Trudeau to provide large fiscal supports during global crises in 2008 and 2020. Harper largely reversed the increase in federal debt relative to GDP caused by the global financial crisis before his political mandate ended in 2015. While it will take longer to reverse the fiscal deterioration caused by the global pandemic, will Trudeau endeavour to put Canada’s fiscal trajectory on a similar path?

The Canadian economy is slowing down in response to significant monetary tightening over the past year. Whether there will be a soft landing (weak growth) or a hard landing (a recession) remains an open question and a planning challenge for Budget 2023.

The good news is that the year-over-year inflation rate is trending towards the Bank of Canada target range of 1 to 3 percent — down almost 3 percentage points to 5.2 percent in February. The other good news is that the labour market is strong – the unemployment rate sits at 5 percent – a half percentage point lower than the rate going into the pandemic. The further good news is that numbers on credit delinquencies and mortgage in-arrears have not yet moved up. After a year of high and rising inflation, household balance sheets across the income spectrum remain in relatively good shape.

The less good news is that warning signs for a growth slowdown have arrived. Financial instability has started in banks in the US and Europe. Canada has seen the flattening of consumption and investment late in 2022. Housing prices have been in decline since last summer. The carrying costs of mortgages are rising fast. Survey data from financial officers and businesses are pointing to financial tightening and lower output.

In economic cycle terms, the data suggest we are at an inflection point. It is difficult to believe that given the amount of debt in the Canadian economy and the 4 percent-plus increase in policy interest rates (with corresponding increases in effective household and business rates) within a year, in addition to quantitative tightening which has flattened the growth of the money supply, that something worse than a soft landing is probable. Budget 2023, like the 2022 Fall Economic Statement, must plan for both a soft and less-soft landing scenario for the economy.

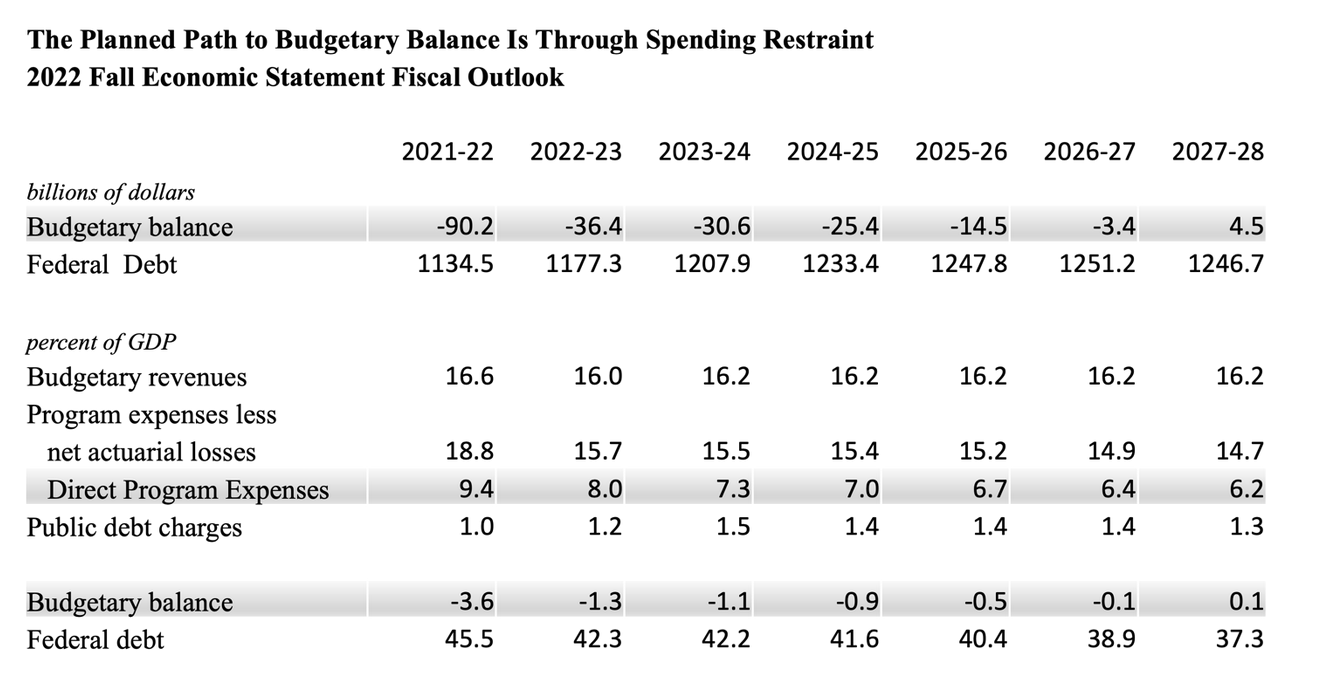

Table 1

Table 1 highlights the fiscal plan of the government as presented in the 2022 Fall Economic Statement. It is a prudent fiscal track. The government can make the claim that it is coherent with the Bank of Canada monetary policy approach. Deficits in absolute dollars and as a percentage of GDP fall over the medium term starting with a modest deficit in 2022-23. It is a gradual approach to budget balance in a slow-growth and high-global uncertainty environment. The debt-to- GDP ratio (the government’s only fiscal rule) falls gradually over the planning framework.

Can the government maintain this fiscal track? The last two fiscal documents (2022 Fall Economic Statement and Budget 2022) both included a modest amount of net new measures in the range of $30 billion over five years. These measures were financed effectively based on higher revenues from an improved economic outlook (higher growth and inflation). The government cannot realistically expect an improved economic outlook since the fall statement. Bottomline, if they do not wish to raise taxes or restrain spending, the planned deficit track is likely to go higher to finance a range of public commitments. Holding the deficit flat over the next four years would generate about $80 billion in additional deficit-financed fiscal room.

Table 1 also illustrates that the principal driver of the fiscal plan to achieve a balanced budget over the next three to four years is spending restraint, particularly related to something called direct program spending. This component of spending includes the operations of the government and transfers (e.g., grants and contributions) across a wide range of departments, from Agriculture to Veterans Affairs. As a share of GDP, planned direct program spending falls significantly and accounts for 100 percent of the decline in the budgetary balance. The government has yet to provide the strategy and spending plan that can achieve this level of restraint.

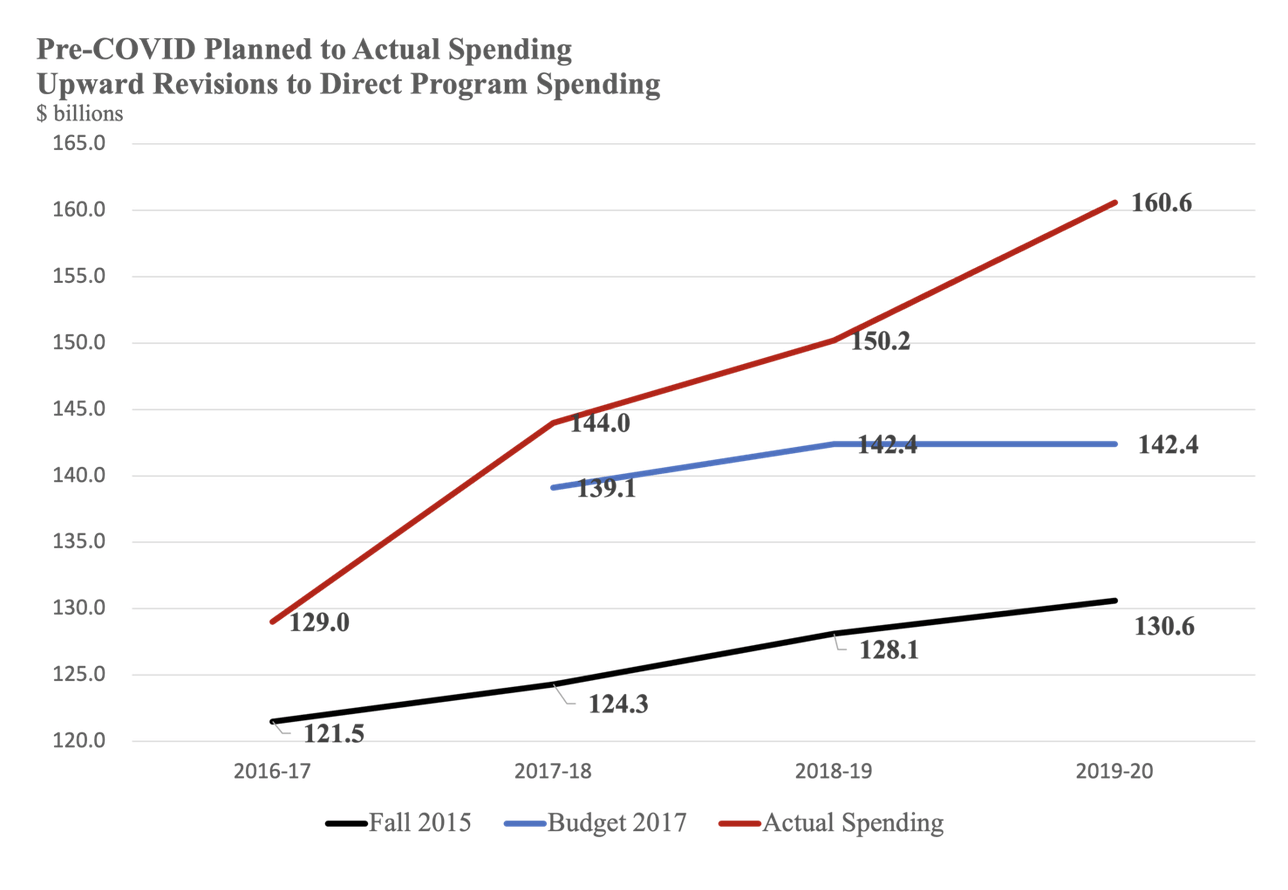

Chart 2

Note: For comparative purposes, direct program expenses include net actuarial losses. Recent federal documents have been separating out this accounting adjustment, which is sensitive to changes in interest rates. It also includes fuel charge proceeds returned.

When looking at the history of the planned and actual profile of direct program spending under the Liberal government, one can see a persistent ratcheting up in the level of spending from successive budgets and updates (Chart 2). This raises the question of the credibility of the Liberal fiscal plan to get to a balanced-budget fiscal stance over the medium term. When push comes to shove, the Liberal government has shown a deficit bias through higher spending.

It has been said that, “Wisdom is knowing the right path to take. Integrity is taking it” (M.H. McKee). Current data suggest the Canadian economy is slowing. The inflation rate remains high but is declining. There is significant uncertainty about the impact of policy lags related to monetary tightening and the evolution of the Russia invasion of Ukraine. At the same time, global economies face an historic challenge of addressing energy transition and climate change. We need wisdom and integrity.

Budget 2023 must outline the strategy, priorities and policies to address these challenges without impairing opportunities for future generations and governments with high public debt. If we need new government spending to address challenges, let’s hope we can find the integrity to raise revenues or restrain less effective and efficient spending and stay the course on deficit reduction.

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, former Parliamentary Budget Officer and a Contributing Writer for Policy Magazine.

Alex Eikre and Zhihan Li are undergraduate economics students at the University of Ottawa.