Budget 2024 Preview: The State of the Nation’s Finances

By Yasmine Hadid and Kevin Page

February 26, 2024

This piece is part of our Policy Budget 2024 preview series.

As Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland and the Department of Finance busily prepare Budget 2024, the state of the nation’s finances are (pause) okay: Not great, not bad.

Elevated debt, inflation and new budgetary constraints should limit deficit-financed spending in Budget 2024, including new long-term programs such as newly-agreed pharmacare. To finance upcoming election promises, political parties will need to get serious about spending review and reallocations. Public opinion polls and expert commentary highlight Canadian concerns about debt. Fiscal responsibility will be an election issue, alongside health care, housing and affordability.

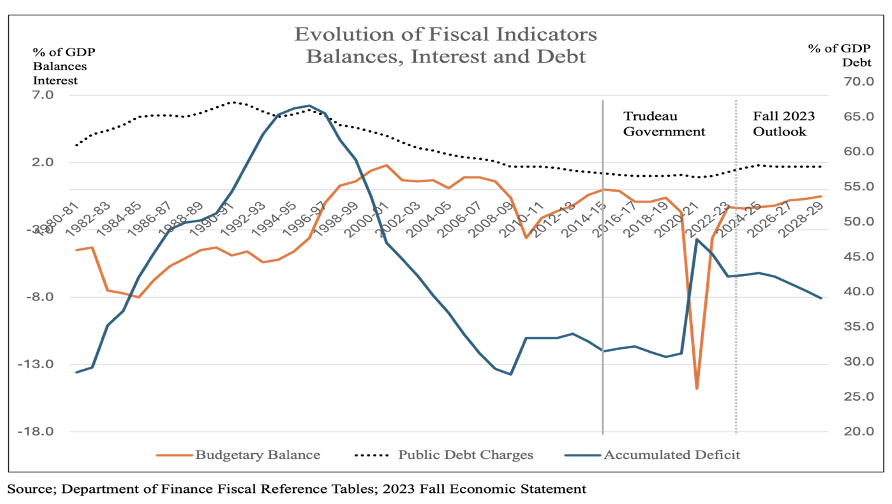

Chart 1

William Shakespeare said “There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so”.

The government made its case for fiscal responsibility in the 2023 Fall Economic Statement, which included two clear indicators. One, the lowest deficit-and net debt-to-GDP ratios in the G7. Two, the fastest rate of fiscal consolidation (unwinding of COVID supports) since the pandemic (highlighted by comparative declines in the deficit-to-GDP ratio). The AAA credit rating remains. If all things are relative, this is evidence that Canada has not lost its good standing.

On the other side of the argument lies a long list of credible experts that make the argument that fiscal responsibility is more complex than selective international fiscal comparisons.

Many experts will argue that some measures of debt (e.g., gross liabilities) are less favourable when looking at Canadian international standing. True. Important relative comparison with deficits, interest costs and debt are domestic. We have lost significant fiscal room since the end of the Chretien/Martin and Harper governments. True. The current government fiscal rule of a declining debt-to-GDP ratio has proven weak. The PBO has shown the government has used positive changes to the economic outlook to finance additional spending. True. If one changes assumptions on spending and interest rates, the government’s claim (supported by PBO and IFSD analysis) that our federal fiscal structure is fiscally sustainable is jeopardized. True (the proof is in the strength of the assumptions).

Chart 1 highlights the federal fiscal roller coaster ride. Large annual consecutive budgetary deficits (5 to 6 percent of GDP) and high interest rates resulted in a mountain of debt in the 1980s. Debt relative to GDP came down sharply in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the governments of Jean Chretien and Paul Martin ran annual budget surpluses facilitated by annual targets and a growing economy. The improvement in fiscal position created opportunities for the Harper and Trudeau governments to support the Canadian economy during global crises. Debt crept up during the financial crisis (2008) and then significantly during the pandemic (2020). Public trust in government (and favourable public opinion) tend to increase during recessionary periods when governments provide large supports. The reverse is true after these periods when governments consolidate public finances.

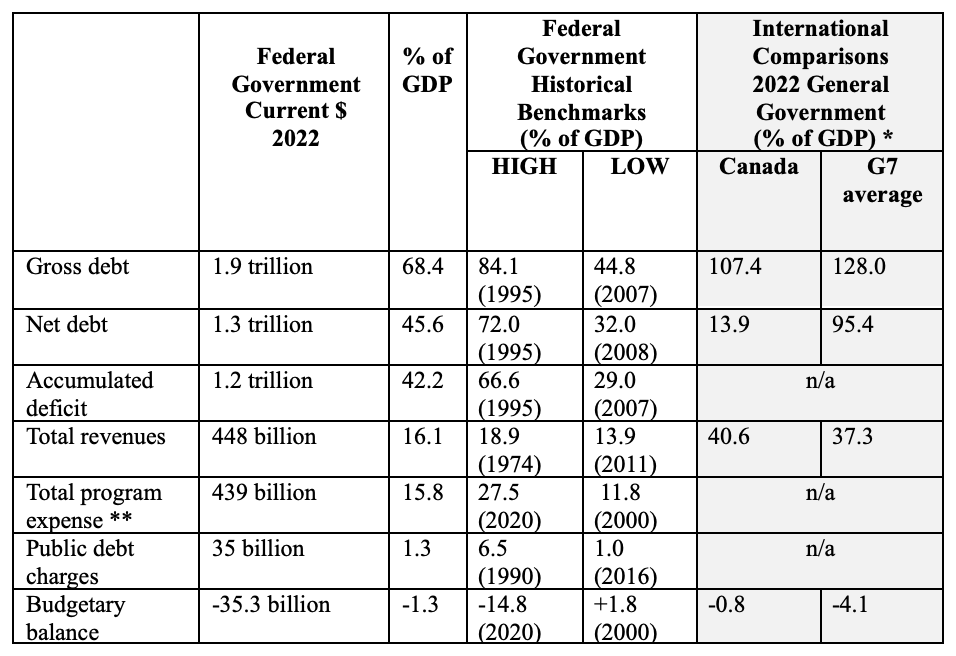

Table 1 highlights current fiscal numbers and makes some historical and international comparisons. Bottomline, the nation’s finances are okay. Not great, not bad.

Table 1 Fiscal Indicators in Historical and International Context

Notes: (*) International comparisons include all levels of government. (**) Program expenses are net of actuarial adjustments

Source: Department of Finance: International Monetary Fund

The government is right with respect to international comparisons – many other countries are doing less well. The critics are right with respect to the loss of fiscal room. Deficits, interest costs and debt are elevated in the immediate aftermath of the COVID pandemic. Our financial situation is not as bad as the 1980s and early 1990s, but we have lost a lot of fiscal room. It is room that is needed to support Canadians in future global crises. International comparisons also highlight that we are a relatively high-tax economy (a large public sector). Fiscal room may best be found by reducing spending.

Current budgetary deficits and public debt interest charges relative to GDP are nonetheless modest compared to recent experience, international benchmarks and a weak economy. The question for Budget 2024 is, “Where do we go from here?”

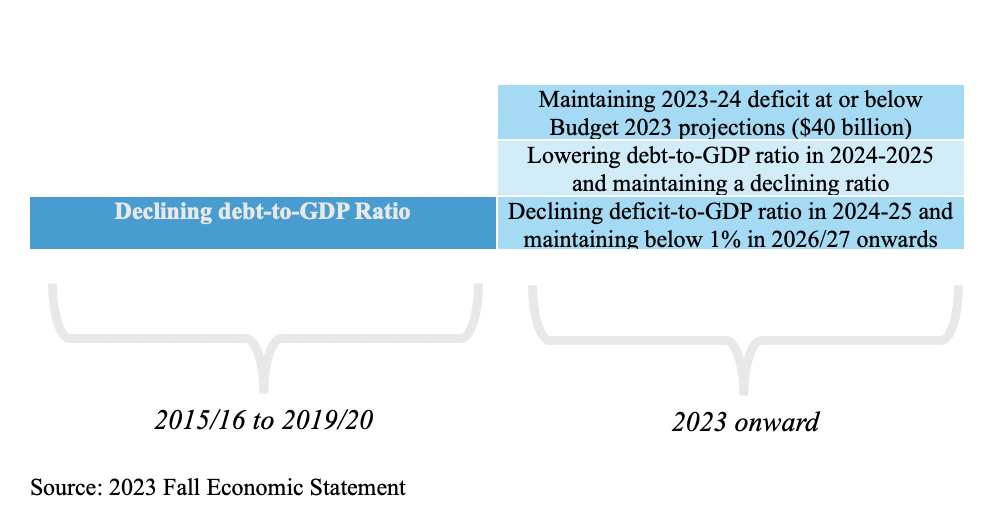

Chart 2 Evolution of Budgetary Constraints

The 2023 Fall Economic Statement indicated the government is prepared to set annual budgetary deficit targets in addition to the declining debt-to-GDP fiscal rule over the medium-term (Chart 2). This is a win for the critics. Holding a modest budgetary deficit constant in nominal (current dollar) terms during a period of weak economic growth (2024) is fiscal restraint. Parliament must hold the government to account on shrinking the budgetary deficit in the years ahead. It means not deficit financing new long-term programs (e.g. pharmacare). This will help replace the fiscal room lost to address the next global crisis.

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, former Parliamentary Budget Officer and a Contributing Writer for Policy Magazine.

Yasmine Hadid is an undergraduate economics student at the University of Ottawa.