Budget 2024 Preview: Time for the Long View

By Kevin Lynch and Paul Deegan

February 29, 2024

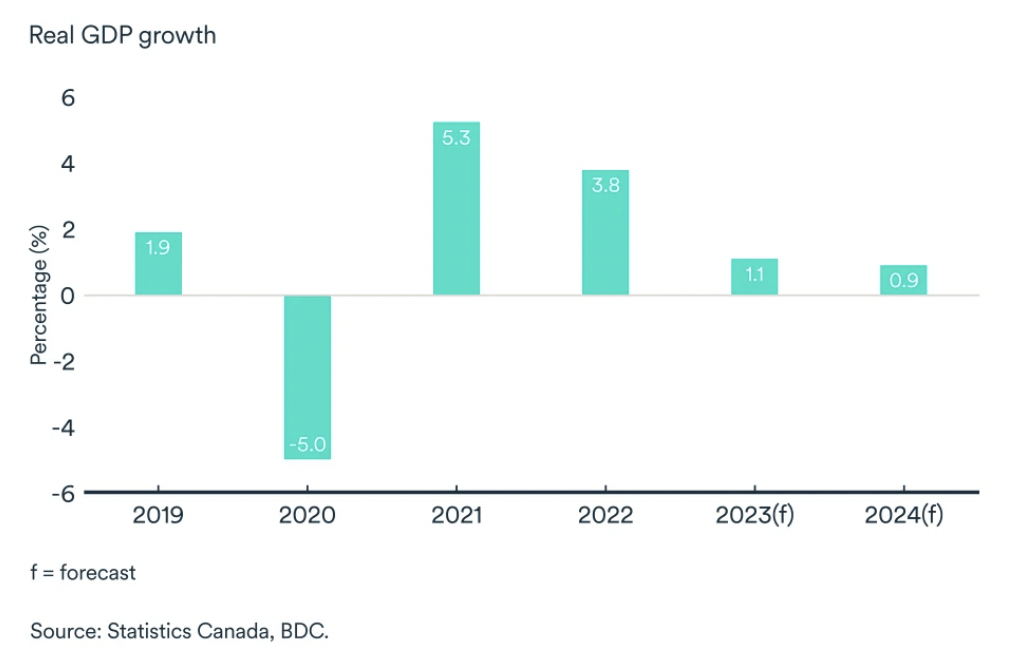

A year ago, we wrote in these pages that “The ‘new normal’ for Canada is slow economic growth.” We wish we could say what a difference a year makes, but we can’t. Growth seems stubbornly mired well below two percent, barely half of what we averaged over the last half-century. Our weak productivity is translating into weak GDP growth and worse – negative per capita income growth.

In 2023, Canadians felt the sting of higher prices and higher interest rates. While we will likely see an easing of interest rates in the second half of 2024, inflation is not proving to be ‘transitory’; it remains ‘sticky’ and we are not out of the woods yet. While Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem has faced political heat, he has proven to be a capable and unflappable manager of monetary policy, hiking interest rates 10 times between March 2022 and July 2023. And yet, housing unaffordability and rapid growth in the cost of living are stressing many Canadians. Here, the Bank’s anti-inflation fight is hampered by rapid growth in government spending, an unprecedented surge in immigration putting pressure on housing and social services, and a myriad of regulations at all levels of government impeding the needed burst of home building.

Global tensions are sky high. While the war between Israel and Hamas hasn’t turned into a full-blown regional conflict, Houthi militant attacks in the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea have already disrupted shipping through the Suez Canal. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s military aggression in the Indo-Pacific region both have the potential to cause shocks to the global economy in 2024. Moreover, no matter the winner of the U.S. presidential election in November, the outcome will be a more protectionist America.

Against this rather gloomy but realistic backdrop, what should Canada do? Here are five ideas.

First and foremost, it is time to begin to restore our fiscal credibility. This is the clear policy advice of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to governments: “The answer is to implement a steady fiscal consolidation, with a non-trivial first installment. Promises of future adjustment alone will not do.”

Ottawa should take heed.

There is nothing like a crystal clear and credible fiscal anchor to earn the trust and respect of capital markets. A fiscal anchor also has the benefit of imposing stricter fiscal discipline within government. Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio was essentially halved from 78% in 1996 to 39% in 2007. Tough decisions during the Mulroney and Chretien years that put us on a more sustainable path gave the Harper and Trudeau governments the fiscal capacity to weather the shocks of the Great Recession and the COVID pandemic. But our fiscal buffers have been depleted, and we need to take steps today to boost our resiliency for tomorrow’s inevitable shocks.

Budget 2024 provides an opportunity to impose fiscal limits that will force government to make tough-but-necessary spending and revenue choices. Simply put, debt-to-GDP needs to come down significantly. To get us there, growth in federal expenditures must be less than the growth in government revenues. In business parlance, that’s ‘positive operating leverage’, and it’s time to look at government’s financial stewardship through this lens. Reallocation – not debt – should be the primary means of financing new priorities.

The “debt-doesn’t-matter” crowd has been proven naïve and foolish in the face of soaring interest rates and mountains of public and private debt. Our consolidated (federal and provincial) government gross debt, which does not get enough attention in these high-interest-rate times, was over 105% of Canadian GDP in 2022, about 30% higher than the average of the prior 40 years. And, according to the IMF, interest rates are not returning to the low levels we experienced over the 2015-2022 period, even when inflation moves back to the inflation targets because of the 4 Ds: deglobalization, demographics, debt, and decarbonization.

The simple reality is this: The more we spend on debt servicing, the less we have to invest in health care, education, defence, old age pensions and infrastructure.

To help create the environment for declining inflation and lower interest rates, the government should complement monetary policy – not compete against it with large increases in spending and hefty deficits. Leaving the Bank of Canada to fight inflation alone with monetary policy will only prolong and heighten the pain of getting inflation and inflation expectations back into the Bank of Canada’s two-percent target range.

This means real fiscal restraint and tough choices. We need to focus on long-term growth investments, rather than on consumption spending. Prime Minister Chretien’s primary funding source for making new long-term investments was reallocation – not piling on more debt. There is room to scale back the bloated size of the public service, which has ballooned by 36%, or 100,000 employees, over the last decade, while the economy has grown by less than 20%. Consultant spending is much too high and poorly managed to boot. Energy transition spending is massive but scattered confusingly across government, making it a prime candidate for an effectiveness and performance review. In short, government operations should be leaner, nimbler, and focussed on excellence in service delivery, employing state-of-the-art digital tools and automation.

Second, against the backdrop of the U.S. presidential campaign and the mandated 2026 review of the CUSMA, we need to diversify our trading relationships. With over one billion people, increased focus should be on opportunities across the Americas. In Asia, Japan and South Korea are complementary economies with strong technological capacities and democracies. In the EU, we need to take better advantage of CETA and build stronger bilateral ties with countries with strong advanced manufacturing sectors such as Germany. Since the 1997 Canada-Israel Free Trade Agreement, two-way trade merchandise has more than tripled, but our own tech hub can learn much from Start-Up Nation, which has more start-ups and unicorns per capita than any other country. Budget 2024 should make long-term trade-enabling investments to ensure that the Canada-U.S. border becomes even more fluid to move goods rapidly and to refocus our trade commissioner network strategically to help businesses develop new markets.

Third, to re-ignite Canada’s dismal productivity growth, which is key to growing GDP and living standards, we need to better encourage business and public investment. Our regulatory framework – across a multitude of sectors, is overly burdensome, complex, and unpredictable. Approvals take too long. This scares away scarce capital. Our internal barriers to trade are an “own goal” on productivity and competitiveness. According to a report from Statistics Canada, they add up to about a seven per cent tariff on interprovincial trade. More competition in key sectors is clearly needed and the proposed comprehensive modernization of the Competition Act should give the Competition Bureau the tools it needs to be more effective. And we need to directly support business investment by allowing companies to continue to take full advantage of the Accelerated Investment Incentive by preserving the current rate.

Fourth, with an immigration-driven population surge placing unsustainable pressures on housing and social services, we need to restore balance and integrity to the immigration system. Canada needs immigration to grow and prosper, and has long relied on a transparent, points-based system with strong public support. But recent policy decisions have led to a more than doubling of foreign students, an even larger increase in temporary foreign workers, and a spike in asylum seekers. Taken together, they account for an unparalleled increase in Canada’s population in 2023 of almost 1.5 million. This, not surprisingly, is placing huge pressure on housing, health care, and social services. It is also making the Bank of Canada’s fight against inflation more difficult; and it is contributing to negative per capita growth. Budget 2024 would provide the economic and policy context to return to, as Tony Keller in The Globe and Mail has advocated, a “pro-immigration, pro-economic growth policy” that meets our long-term needs and short-term circumstances.

Finally, given the wicked challenge of climate change, Budget 2024 is an opportunity to provide greater clarity on the government’s policies, targets, and milestones. The federal carbon tax policy is uneven in its application and unclear in its public understanding. Energy transition plans make little mention of expanding hydroelectricity – although Canada is the fourth-largest hydroelectricity generator in the world, our current permitting processes are effectively preventing new dams, plants, and power lines from even hitting the drawing board. Despite being a leader in nuclear energy, there is little federal government support for building new reactors to replace fossil fuel electricity generation. Investments in small nuclear reactors, which hold great promise, have been modest and largely led by provinces. And, as the world’s fifth-largest natural gas producer, it is in our interest to push for a new global credit system, where exported gas that is substituted for coal in other countries receives a credit against the national emissions target of the exporting country – simultaneously lowering overall emissions globally, helping Canada meet our climate goals and supporting our gas sector, which is a major source of export revenues and taxes.

Canada has tremendous opportunities, but our structural problems are putting those opportunities at longer-term risk. To avoid saddling future generations with mediocre economic prospects and diminished global influence, we require clear-eyed solutions embedded in long-run plans. The times demand that Budget 2024 take such a long-run view, but that means tough choices, inevitable trade-offs, and short-term pain for future gain. It will be interesting to see whether any party is willing to advocate such an approach with an election coming in the next 18 months.

Kevin Lynch was Clerk of the Privy Council and vice chair of BMO Financial Group.

Paul Deegan was a public affairs executive at BMO and CN, and he worked in the Clinton White House.