Canada’s Housing Crisis and the Need for a National Infrastructure Assessment

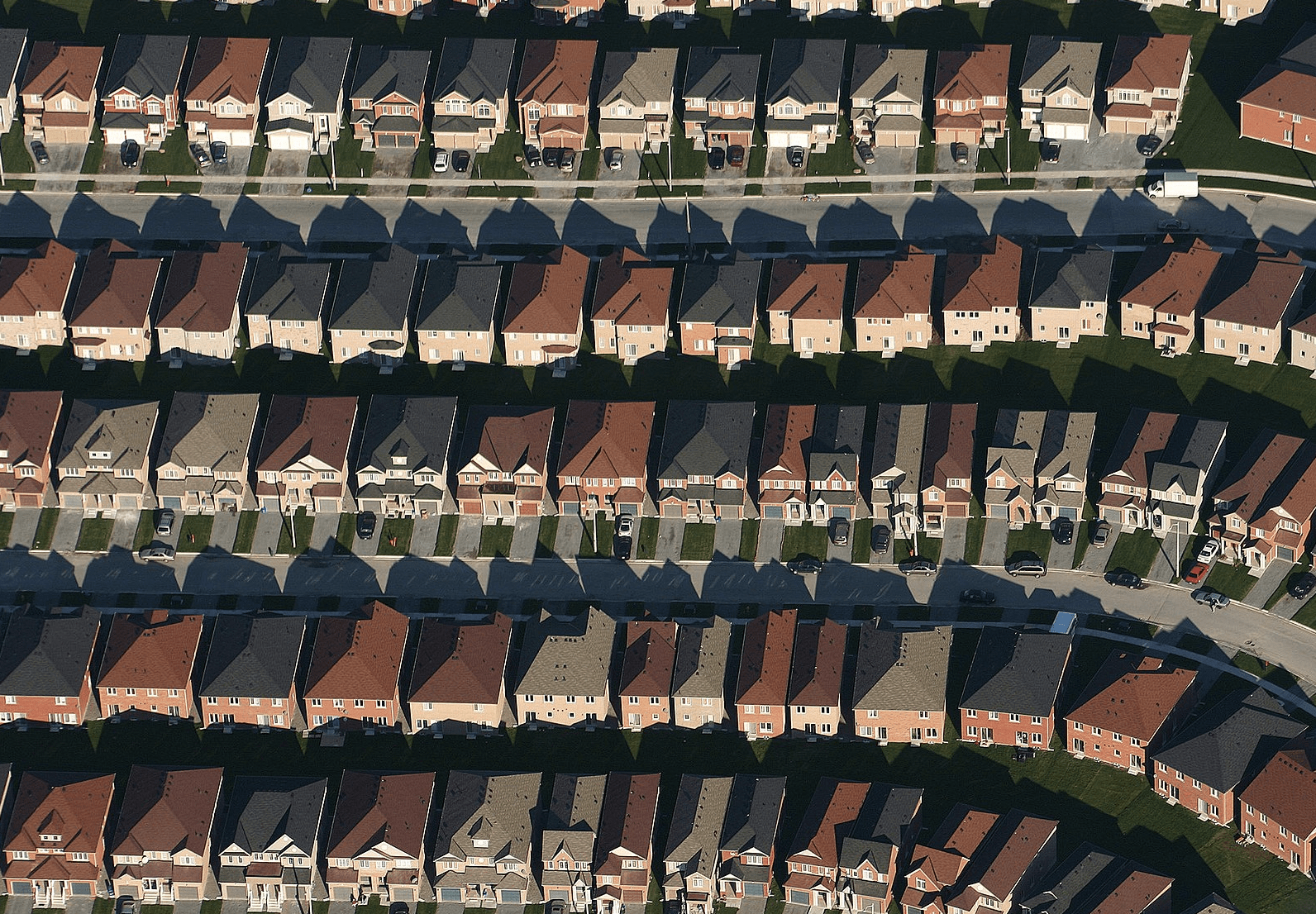

Aerial view of Markham, Ontario/iDuke

Aerial view of Markham, Ontario/iDuke

By Ian Lupton

May 2, 2024

To close Canada’s housing gap will take significant, strategic infrastructure investment. For that investment to be as efficient and effective as possible, the government needs to deliver a National Infrastructure Assessment.

Tellingly, the federal government was pursuing meaningful action on this file.

Budget 2021 contained a $22.6M allocation to support the initial work of an NIA. Infrastructure Minister Catherine McKenna launched public engagement in March 2021. In July 2021 the Government released Building Pathways to 2050: Moving Forward on the National Infrastructure Assessment, intended to guide the design of the NIA. In his December 2021 mandate letter to then-Infrastructure Minister Dominic LeBlanc, Prime Minister Trudeau directed that the NIA be launched “to help identify needs and priorities in the built environment and support long-term planning toward a net-zero emissions future”.

Fast-forward to this year. Budget 2024 contains billions in new funding and loans to build 3.87 million new homes by 2032, outlined in Solving the Housing Crisis: Canada’s Housing Plan. The $15BApartment Construction Loan Program is intended to bring 30,000 new rental units online, and a $400M top-up to the Housing Accelerator Fund will provide direct funding to municipalities to speed up homebuilding. Importantly, the federal budget also includes $6B for water and wastewater infrastructure through a new Housing Infrastructure Fund, essential to new home construction. But where’s the plan?

“Growth pays for growth” is a shibboleth in municipal planning and engineering departments across the country. Its meaning: new development, not taxpayers, should pay for the infrastructure required to support it: roads and transit; watermains and wastewater facilities; utility lines, parks, and stormwater management. Housing requires all these investments to be viable and attractive.

But how are infrastructure needs understood when the country is facing unrelenting housing demand, a multimillion housing-unit gap, and soaring home prices? And how do infrastructure costs affect housing affordability?

Development charges (DCs) – fees to pay for infrastructure – drive up hosing costs. They are levied by municipalities on developers, then passed along to buyers of new buildings. Popular for decades, DCs and other fees have grown to comprise upwards of 20% of the cost of new housing. In many parts of the country, these fees add more than $100,000 to the cost a new home.

The Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) estimates that, with $107,000 of infrastructure spending required per housing unit, a $400B investment in infrastructure is necessary to bring those 3.87M new homes online.

Any spending shortfall of such size begs for a plan and prioritization on how to address it. And local communities are already facing staggering shortfalls in capital infrastructure and renewal budgets.

Governments at all levels need to invest more, and more strategically, in housing-enabling infrastructure. And governments are beginning to understand the importance of this relationship more clearly.

In July 2023, the federal government merged the housing and infrastructure portfolios when Sean Fraser was named Minister of Housing, Infrastructure and Communities. Its $6B federal Housing Infrastructure Fund is, at least, a start. And recently the Ontario government announced a $1B Municipal Housing Infrastructure Fund of its own.

The FCM has called for a Municipal Growth Framework, to establish new federal investment and for a commitment to convene a national conversation among orders of government to develop a new approach to municipal growth.

Governments at all levels need to invest more, and more strategically, in housing-enabling infrastructure. And governments are beginning to understand the importance of this relationship more clearly.

The relationship between infrastructure investment and housing has never been clearer. And with higher public debt levels and interest rates, all government expenditure must be made more efficiently and effectively.

A National Infrastructure Assessment (NIA) would help governments plan and invest wisely. An NIA would assess infrastructure needs and establish long-term vision; improve coordination among infrastructure owners and funders; and determine best ways to fund and finance infrastructure. An NIA would help lay the foundations necessary to address the housing crisis. And an NIA would provide other economic, social policy and governance benefits.

The current federal government – or its successor – should deliver a National Infrastructure Assessment. Adequate resources and aggressive timelines are essential. Core infrastructure needs vary across the country. According to the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy’s report on Infrastructure and Investment Planning, “Canada needs to define national and sectoral plans to determine in what to invest and where. A needs assessment to identify current and future needs should drive plans.”

An NIA is good economic policy. Governments invest billions in public infrastructure each year. Canada’s largest industry as a percentage of GDP is housing. Investments that spur more of both is good – for the country, and for neighbourhoods.

Identifying infrastructure deficiencies and prioritizing investment will allow for smarter public spending. Strategic investment will enable sustained, long-term growth by increasing productivity. New neighbourhoods, economic centres and transportation routes will be planned, and predictable. Existing ones will be renewed. People, goods and ideas will move more efficiently. Projects can be prioritized based on regional, population, employment and GDP growth targets. A comprehensive plan provides confidence and stability. Infrastructure can attract significant private sector investment as long-term investors seek lower-risk investment opportunities infrastructure provides.

An NIA bolsters other policy objectives. It encourages environmental sustainability by linking infrastructure and housing with transit-oriented development. Infrastructure planning mitigates environmental impacts on natural lands and waters. Climate resilience improves as the environmental assessment process is better informed. An NIA can support social policy and equity goals by informing plans to build educational, healthcare, recreational and transportation services. An NIA can also foster intergovernmental relationships. Provinces, territories and municipalities can make needed investments in critical infrastructure, using information – and funding – from the federal government.

A robust assessment of infrastructure needs promotes transparency and accountability across governments. The Assessment would be based on comprehensive public data, clear evaluation criteria and analysis. Decision making processes would be open. Documentation and regular reporting would enable public scrutiny. Governments will always consider the political economy of spending; however, a National Infrastructure Assessment and an independent advisory committee could help curb the most extreme of these impulses.

Australia enacted legislation in 2008 and created an Infrastructure Assessment Frameworkand an Infrastructure Plan. Together they are used to develop a national Infrastructure Priority List. The United Kingdom’s National Infrastructure Assessment and National Infrastructure Commission also offer useful models of how an assessment can be undertaken and an advisory commission can operate.

A Canadian National Infrastructure Assessment will facilitate more homebuilding. It will strengthen provinces and territories, cities and rural areas, by supporting a broad range of economic, social and environmental policy objectives.

It is overdue.

Ian Lupton is a master’s candidate at the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. He has worked in legislative, provincial and municipal governments in Canada and the US. Ian is interested in the public realm and how public policy can be used to improve everyday lives for citizens.