Canada’s Opportunity to be a Global Food Superpower

Reuters

Reuters

Charles McMillan

January 23, 2023

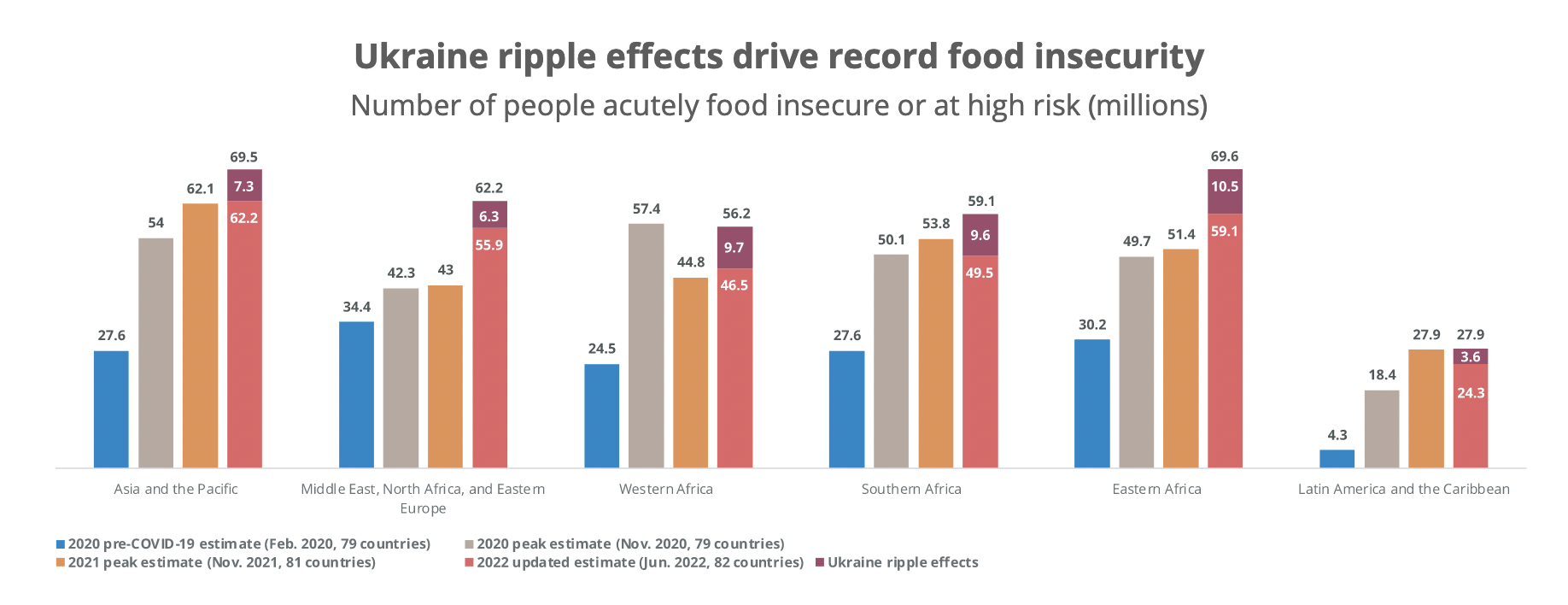

Climate change, COVID-19, and the war in Ukraine are just some of the crises that have exposed an unfortunate new reality — our global food supply is perilously insecure. Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, whose food exports directly and indirectly impact almost two billion people, has impacted many in the poorest countries. Inflation that has been attributed to the war and to supply chain disruptions hasn’t helped. Climate change and the resulting impacts on extreme weather patterns of drought, flooding, forest fires, water shortages and unprecedented temperature conditions have impacted agriculture and growth across more and more of the world. And yet, this crisis — per the eternal aphorism — also presents an opportunity for Canada to take its place as a global food superpower.

The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) reports that a record 349 million people across 79 countries now face acute food insecurity – up from 287 million in 2021. “This constitutes a staggering rise of 200 million people compared to pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels,” per the WFP. “More than 900,000 people worldwide are fighting to survive in famine-like conditions. This is ten times more than five years ago, an alarmingly rapid increase.”

There’s another eternal aphorism — it surfaces at times of popular uprising and informs major supply-securing, stability-ensuring strategies such as China’s — “When the people go hungry, governments topple.” It also illustrates the connection between food security and national security; not in the protectionist sense, but in the sense of governments having a responsibility to see human security, food security and national security as intertwined from a policy perspective.

Canada’s core agricultural strengths — abundant and fertile soil, the legacy of animal and plant husbandry, and superior farm methods to achieve higher yields and better nutrition outcomes — have helped make Canada a leading food exporter. Indeed, Canada’s province-by-province presence in all aspects of the food value chain — from farm crops and animals to leading commodities such as wheat, soybeans, corn, canola, fruits, vegetables, and seafood — has positioned the sector to reach higher aspirational output.

In fact, the many disruptions and threats to the world’s agriculture and food production sector now present Canada with an unprecedented chance to be a forward-looking, top-five exporter of food that goes beyond our traditional products (wheat, potatoes, corn, meat and seafood) to include meeting the growing demand for the protein ingredients of plant-based diets, including beans, peas, chickpeas, and lentils, plus new varieties of vegetables, food commodities, and beverages, including wine, health drinks, and high value-added liqueurs.

Why is Canada so well positioned? In short, because climate change, technological innovation, and food security are the new urgencies of a global food sector in which food abundance and food shortages coexist, even among advanced countries such as Britain and America.

World Food Programme

World Food Programme

That dichotomy of overabundance and scarcity is documented in the UN’s 2021 Food Waste Index Report, with waste as high as a trillion dollars, or about 17 percent of total food produced and available in 2019 ending up in the garbage. Indeed, if all the wasted food was placed on large 40-ton container trucks, the convoy of 23 million cargo vehicles travelling bumper-to-bumper would encircle the world eleven times.

By any measure, the agriculture and food production system has become a knowledge industry, both domestically and globally. Massive advances have been made in related fields such as veterinary medicine, the natural sciences like biology and chemistry and the many related disciplines including economics, and the applied areas of agricultural economics, production planning, and data analytics. Today’s digital society offers agriculture new tools ranging from drones to smart tractors to smart crop imaging, and most impactfully, smarter farmers. In 2021, Canada’s agriculture and agri-food system employed 2.1 million people, provided one of every nine jobs and accounted for 6.8 percent of Canada’s GDP.

Among advanced countries, the myth of a pure market-driven system, (often expounded by the party rhetoric in the US political system), is laid bare by market-distorting policies at both the state level in farm states and by federal policies in Washington and across other capitals. A 2021 study by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) found $540 billion in global subsidies was given to farmers every year between 2013 and 2018.

Today, food production faces headwinds not only from climate change, but political action related to food security. This new feature goes beyond domestic policy. Trade has become a contested issue in the global agriculture and food environment, not just for emerging markets and China, but for farm and agricultural nations like Japan, Canada, Britain, and France. Smaller countries with limited domestic size forced to export to foreign markets to achieve economies of scale, reach critical mass to apportion research costs, and fund the necessary infrastructure for a modern farm economy.

Designing forward-looking, pro-active agricultural policy was never simple. As US President Dwight Eisenhower once put it, ‘You know, farming looks mighty easy when your plow is a pencil, and you’re a thousand miles from the corn field’.

Further, political issues also matter to advanced economies beyond domestic policies for a market economy – Canada’s supply management system for the dairy sector, Japanese tariff policy for rice farmers, and Europe’s common agriculture policy are cases in point. Agricultural support can come in an array of models, including those for output quantities or input use, but hundreds of billions of dollars are spent on market-distorting payments.

Designing forward-looking, pro-active agricultural policy was never simple. As US President Dwight Eisenhower once put it, “You know, farming looks mighty easy when your plow is a pencil, and you’re a thousand miles from the corn field.”

Canada’s opportunity to lead comes from strengths across the food value chain, from fertile land — the most important input — to our world-class knowledge and scientific base, our reliable food processing stages of production and supply chains, our federal food safety regime, our retailing infrastructure, system of vet colleges and universities, and our implementation of lessons from the protein and digital revolutions. In some countries, parts of the value chain — the food processing system, especially for meat-based products — are needlessly concentrated, especially in America.

Recent advances in all aspects of novel technological innovation are gaining strength, including through new corporate partnerships, new start-ups at each stage, and novel ecosystem institutions linking education, financial services, the computer sector, food processors and food retailers, and government agencies like Farm Credit Corporation. The growing recognition of climate change and risk mitigation has played a role, but so has the general rule of “follow the money”, as creative entrepreneurs initiate new business models that bring disruption to traditional policies and management systems.

At the same time, thanks to new technologies and scientific progress, internal issues are transforming established practices. Slowly, new start-up firms bring change to incumbent firms, challenge conventional assumptions and set new benchmarks for innovative solutions. These trends are pervasive and international in scope, often reinforced by social media, better access to data, and collaboration with scientists and engineers, NGO activists, and entrepreneurs with a thirst for alternative consumer choices. Resilient organizations now make trial-and-error processes a competitive strength, and a tool to encourage an innovative mindset. Whether knowingly or not, more companies and organizations are adopting the practices of kaizen — the Japanese concept meaning “change for better” whereby continuous improvements are made to all functions based on input from all employees, from the CEO to assembly line workers.

In fact, around the world, including in Canada, there is a new phase of entrepreneurial zeal among actors at each stage of the food value chain, a combination of both incremental innovation and radical transformation that strengthens the new precision agriculture paradigm. Precision agriculture combines new forms of digitization, state-of-the-art supply chain innovations, and organizational forms of collaboration among the stages. New start-up formations attract the flow of venture capital to agtech and accelerate knowledge diffusion. The robust changes facing each stage require new commitments to observe and understand the timelines of product innovation and new business models.

Land mass isn’t everything in the value chain for food production. The Netherlands has used technology and innovation — including advances in greenhouse growth — to become a global food exporting powerhouse. “The Dutch have pioneered cell-cultured meat, vertical farming, seed technology and robotics in milking and harvesting — spearheading innovations that focus on decreased water usage as well as reduced carbon and methane emissions,” per The Washington Post. The Netherlands now exports more than $105 billion euros (about $108.4 USD) in food products, compared to Canada’s $82.5 billion (CAD), making it the world’s second-largest food exporter by value, after the United States. This despite having a land mass half that of Nova Scotia or New Brunswick, and a population only slightly greater than Ontario.

Both the US and the Netherlands show the productive advantages of combining three disruptive changes: the protein revolution, the digital revolution, and the scientific revolution. There is a vital need to break down silos across the value chain, including through closer industry-university collaboration and technology transfer, the leveraging of export markets as a tool for learning, and the vital need to combine the strengths of the private sector with the institutional advantages of the public sector. For instance, the Netherlands is the leading exporter of cut flowers, bulbs, and live plants, distributing them quickly and efficiently from its port in Rotterdam, and Schiphol airport in Amsterdam, Europe’s third largest freight gate, connected to 327 destinations in 98 countries.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

As other industries have shown, in a post-pandemic world, the status quo is not an option. The impact of food waste, unused land, excessive water consumption, and high greenhouse gas emissions requires new thinking and innovative solutions. Net zero targets are the only option, but it takes time to make adjustments. Technology and product life cycles are changing traditional business models, as seen in the auto sector, but it also applies to agriculture and farming.

As in many other sectors, Canadian food production suffers from a mix of perverse incentives, and a silo mentality at each stage of the food value chain, where solving one problem can have compound effects on other stages. For the most part, departments of agriculture at both the federal and provincial levels take a reactionary stance to innovation and emphasize (through time, effort, and financial resources) their regulatory functions. Insufficient time and effort are spent on trade promotion, especially in underserved export markets where food security and shortages are reaching crisis levels.

Politically, the farm sector is seen as a rural issue, not a vital challenge for Canada as a G7 country and a trading partner. Changing Canada’s food system as an export sector to superpower status – one of the world’s top five, compared to being eighth — is a national challenge. It requires new approaches to — if you’ll pardon the on-the-nose metaphors — breaking down silos and flattening fences across borders, among sectors, from institution to institution and between every field of endeavour the depends on, impacts and informs Canadian agriculture from public health to universities to transportation to business to climate research and clean energy.

Canada needs to up its agri-food game with high aspirations. It can start with these five changes:

Start with a global mindset. Canada should host an annual food fair, similar to the two largest, the AUGA in Cologne and FoodEx in Tokyo, to bring together domestic players and international firms, with leading speakers underscore the overlap between agriculture, technology, innovation, climate change, food security, public health, the plight of poor nations, and their need for safe and reliable food supplies.

Second, like the Netherlands, Canada should be in the business of selling farm and food technology, including new software applications for seed distribution, optimum land use, natural ecosystem diversity, and a host of innovative solutions across the value chain.

Third, trade promotion should be the leading target of agricultural departments, and include benchmark targets by country, products, and especially underserved markets where Canadian exports are low or non-existent.

Fourth, Canada’s scientific and academic institutions should be mandated to break down traditional silos across the relevant disciplines, and institute new measures for deep collaboration on agricultural innovation and food security, including with private firms, farm groups, and the small but growing venture capital sector. The fact that in Atlantic Canada, a federal agency, ACOA (the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency) is a leading player in financing start-ups, usually in coordination with private financial institutions, shows how new collaborative ideas are possible.

Fifth, Canada’s leading food processors and retailers, which already have a commanding presence in the domestic market as well as some with exports to the United States, can play a major leadership role. Few Canadians appreciate the international presence of Saputo, now the eighth largest dairy firm in the world, Couche-Tard, also from Montreal, the world’s second largest convenience store (behind Japan’s 7-11), and the international presence of McCain’s, which has investments in Africa’s vast underserved food import market, where the entire continent has only six percent of arable land.

Canada can view climate change, food shortages and food security, and disruptive change from the scientific, digital and protein revolution as a threat or a challenge but also new distinct advantages for job creation, corporate expansion, and export growth. The opportunity to win is Canada’s to lose.

Charles McMillan is Professor of Strategy at the Schulich School of Business, York University and author of several books. His most recent study, The Age of Consequence: The Ordeals of Public Policy in Canada, was published in 2022 by McGill-Queen’s University Press. His new book, Precision Agriculture and Food Production, is to be published by Cambridge Scholars.