C’est l’économie, stupide: In Quebec City, Pierre Poilievre Unveils his Stump Speech

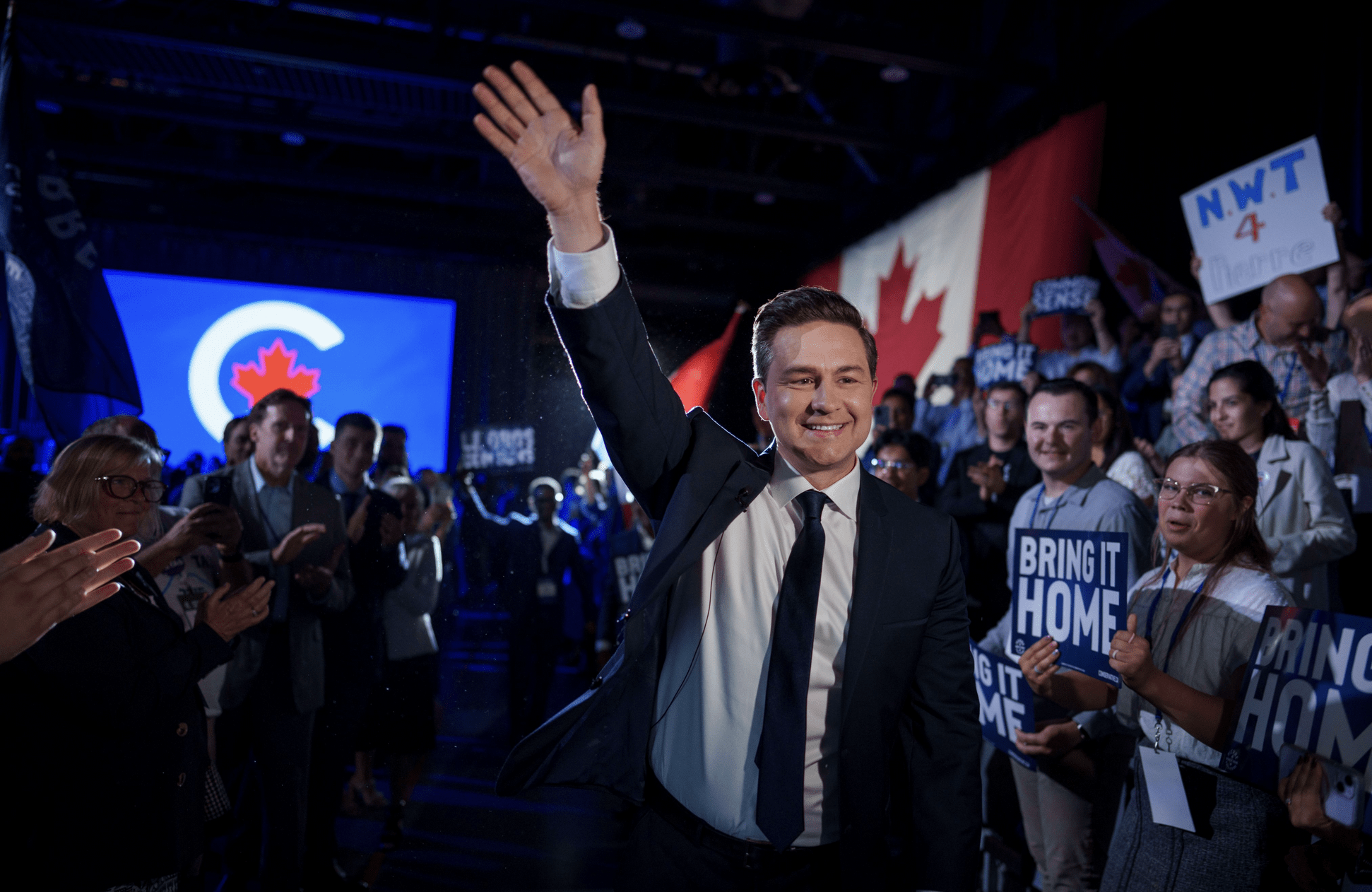

Pierre Poilievre/X

Pierre Poilievre/X

Daniel Béland

September 10, 2023

The fact that the 2023 Conservative policy convention took place in Quebec City was no accident. For Pierre Poilievre, the choice of the historic capital of the party’s toughest province to crack electorally telegraphed multiple messages. Among others, it was a message to the party’s rank and file that having a guy with a francophone last name who is fluent in French could help the party win more seats in Quebec. It also allowed Poilievre to position himself as the real alternative to Justin Trudeau in the minds of Quebec voters who want change in Ottawa.

With the exception of the greater Quebec City area, La Belle Province has been challenging political terrain for conservatives since the Brian Mulroney vague bleue of 1984 upended the conventional wisdom, sweeping 58 of 75 seats, increasing that to 63 in 1988. In 2015, the Conservatives only won 12 seats in the province, and 10 seats at both the 2019 and 2021 federal elections. In fact, since the creation of the Conservative Party of Canada two decades ago, 12 seats is the best the Conservatives have ever achieved in a province that currently has 78 seats in the House of Commons.

Yet, as the Harper years show, the Conservatives do not need to win a large number of seats in Quebec to win federal elections and even get a majority of seats in the House of Commons. In 2011, when they won enough seats across the country to form a majority government under Stephen Harper, the Conservatives had only secured five seats in Quebec in the aftermath of the NDP Orange Wave, which crushed the Bloc (four seats instead of 49 in 2008) and weakened the Liberals (seven seats instead of 14 in 2008) in the province.

Until recently, opinion polls in Quebec were not favourable to the Conservatives but things started to improve this summer, and recent polling estimates that they currently receive between 21 and 25 percent of support in the province. These numbers gave hope to Conservatives ahead of their Quebec City convention, which increased the pressure on Poilievre to deliver a speech Friday night that would appeal to both Quebeckers and people in other parts of the country.

Because the housing and cost of living crisis is hitting he country hard as a whole, the focus of his speech on bread-and-butter issues was inevitable. He did deliver on that front by attacking the Trudeau government’s economic and fiscal record in a context during which high inflation and interest rates are hurting workers and families from coast to coast to coast.

Poilievre stressed that, unlike the Bloc, the Conservatives are the only party that can beat the Liberals in the next federal election, a statement that has the advantage of being accurate.

In more blatantly political terms, specifically for his Quebec audience, the Conservative leader emphasized the fact that key policies adopted by the Trudeau government are also supported by the Bloc. More important, Poilievre stressed that, unlike the Bloc, the Conservatives are the only party that can beat the Liberals in the next federal election, a statement that has the advantage of being accurate.

In contrast to the three previous Conservative leaders, Poilievre has personal ties to both Quebec and the French language that he mentioned in his speech: his Venezuela-born wife Anaida, who grew up in Montreal’s Point-aux-Trembles neighbourhood, and his father Donald, who is a francophone. The fact that he expresses himself better in French than did his recent Conservative predecessors could also help him in Quebec.

Yet, some of his party’s positions on key environmental and social issues are at odds with dominant public sentiments in Quebec, especially in Montreal. Because the Conservatives are not focusing their electoral efforts on Montreal but are instead targeting what is known in Quebec as “the regions,” such controversial positions might not prevent them from winning more seats in Quebec, especially if the next federal campaign is all about the economy.

Poilievre is strongly supported by the party’s base, which gives him the wiggle room to potentially reject some of the electorally risky policy proposals adopted at the Quebec City convention. Still, unlike Erin O’Toole, he is unlikely to suddenly pivot to the centre during the next federal campaign, partly because he might not need to, at least if the Trudeau government’s popularity remains low. What he seems to be counting on is the fatigue that a growing number of people are feeling towards both the Trudeau government and the economic situation, especially the cost of living and housing crisis.

The main challenge for the Conservatives in Quebec and in Canada as a whole is to maintain their current momentum for the months to come. If the next federal election only takes place in October 2025 as scheduled, this is a very tall order, especially because the economic situation is likely change significantly between now and then. Because the NDP is stagnating in the polls and doing a mediocre job at raising money, its leader, Jagmeet Singh might not want to pull the plug on their supply-and-confidence agreement with the Liberals any time soon.

As for the Trudeau government, it needs to put forward bold policies to address the cost of living and housing crisis in its fall economic statement. The recent surge of the Conservatives in the polls over the summer seems directly related to the lacklustre response of Justin Trudeau and his team to a crisis that is hurting Canadians all over the country, including in Quebec, where Poilievre and his party hope to upend conventional wisdom all over again.

Contributing Writer Daniel Béland is Director of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada and James McGill Professor in the Department of Political Science at McGill University.