Charting Spending Under the Liberal Government

By Kevin Page with Yasmine Hadid and Hunter Vanderlaan

April 12th, 2024

Has the Liberal Government under Prime Minister Trudeau increased government spending significantly in economic and historic terms? Yes. Has that spending been impacted by the government of Canada’s fiscal response to the global pandemic and lockdown of 2020-2023? Yes.

Do the Liberals have a credible plan to restrain the growth of spending to achieve their medium-term fiscal targets of planned budgetary deficits under 1% of GDP and a declining debt-to-GDP ratio? No.

Should we care? Yes.

Budget 2024 will be tabled in Parliament by the Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland on April 16, in a difficult policy and political environment. The economy is weak. The list of policy issues is long. Fiscal room is limited. The government is trailing in opinion polls.

Facing these prospects, the government has chosen a strategy to delay budget timing and pre-announcing a list of spending and lending initiatives – pharmacare, national defence, housing, day care, food support, technology, international assistance, among others. The purpose was to maximize public attention on individual initiatives.

The pre-announced budget initiatives will boost spending levels and the financial requirements by billions of dollars per year. We must wait for budget plan to see how these initiatives (and others) will be financed. What proportion will be financed by a better-than-anticipated economic outlook? Or higher-than-planned budgetary deficits? Or offset by spending reductions or higher taxes; or some combination of all?

Budget observers have grown accustomed to the Liberal government pre-announcing new government spending initiatives since it took office in the fall of 2015. In arithmetic terms, this is a government focused on addition and not subtraction. It raises the question of the extent the Liberal government has grown the size of government.

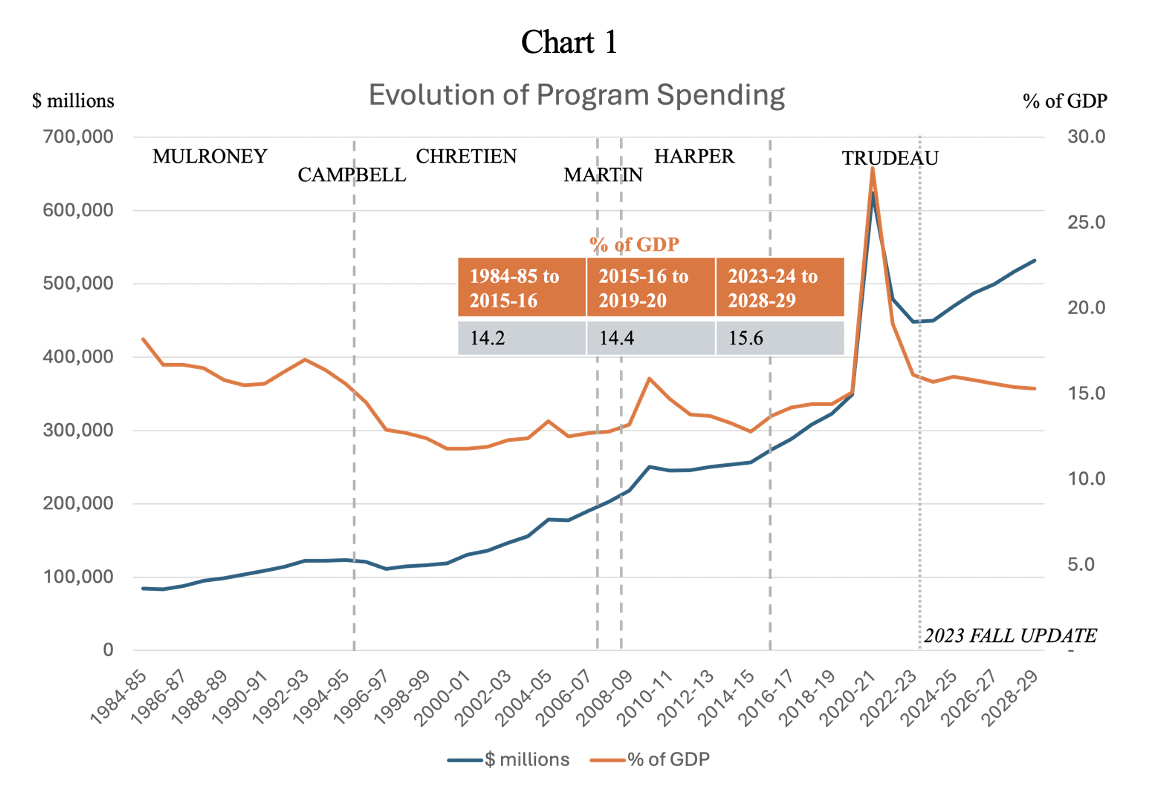

Chart 1 provides a modern historical perspective on federal program spending. Since 2015, the trajectory of program spending has noticeably steepened in current dollar terms. In economic terms, the level of spending relative to the size of the economy is up significantly. Government is bigger under Justin Trudeau, than the governments of Harper, Martin and Chretien.

The global pandemic had an enormous impact on program spending. Direct federal supports for households and businesses were in the 100s of billions of dollars in 2020 and 2021. History was made. Program spending as a percentage of GDP effectively doubled (14.6 percent in 2019-20 to 27.5% in 2020-21). By 2022-23, federal supports were unwound. A relatively strong economic rebound and the reduction of COVID supports brought about the return to more modest budgetary deficits. Spending levels, however, remain elevated in both current dollars and as a percentage of GDP relative to the pre-COVID period.

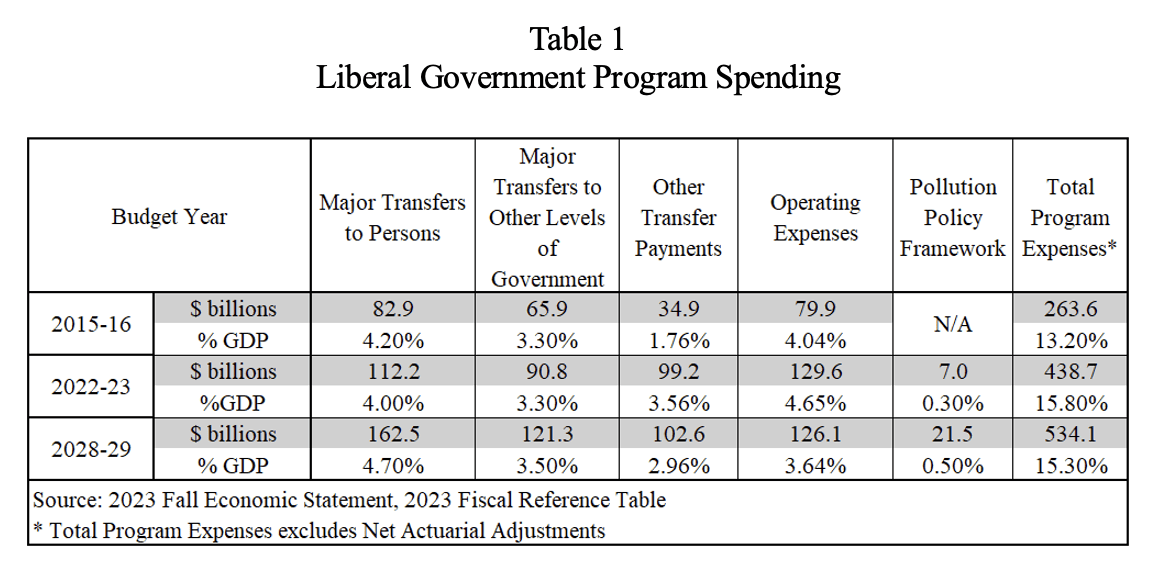

Table 1 deconstructs program spending under the Trudeau government.

Over the period 2015-16 to 2022-23, where we have audited financial statements, program spending increased from $264 billion to $439 billion. As a percent of GDP, program spending has increased from 13.2 percent to 15.8 percent.

In a $3 trillion economy (2024), every percentage point of GDP is equivalent to $30 billion. Since 2015-16, program spending increased by 2.6 percentage points (after the unwinding of the COVID-19 fiscal supports). It is relatively larger than the average increase in spending by advanced economies highlighted in the IMF Fiscal monitor. The spending increase is equivalent to about two times Canada’s commitment to NATO on defence spending.

Table 1 indicates that the relative increase of spending over this period is in direct program spending; not transfers to persons (e.g., elderly benefits); or other levels of government (e.g., the Canada Health Transfer). Direct program spending includes spending on operations (e.g., wages, professional services, capital) and other transfers (e.g. grants and contributions to industry).

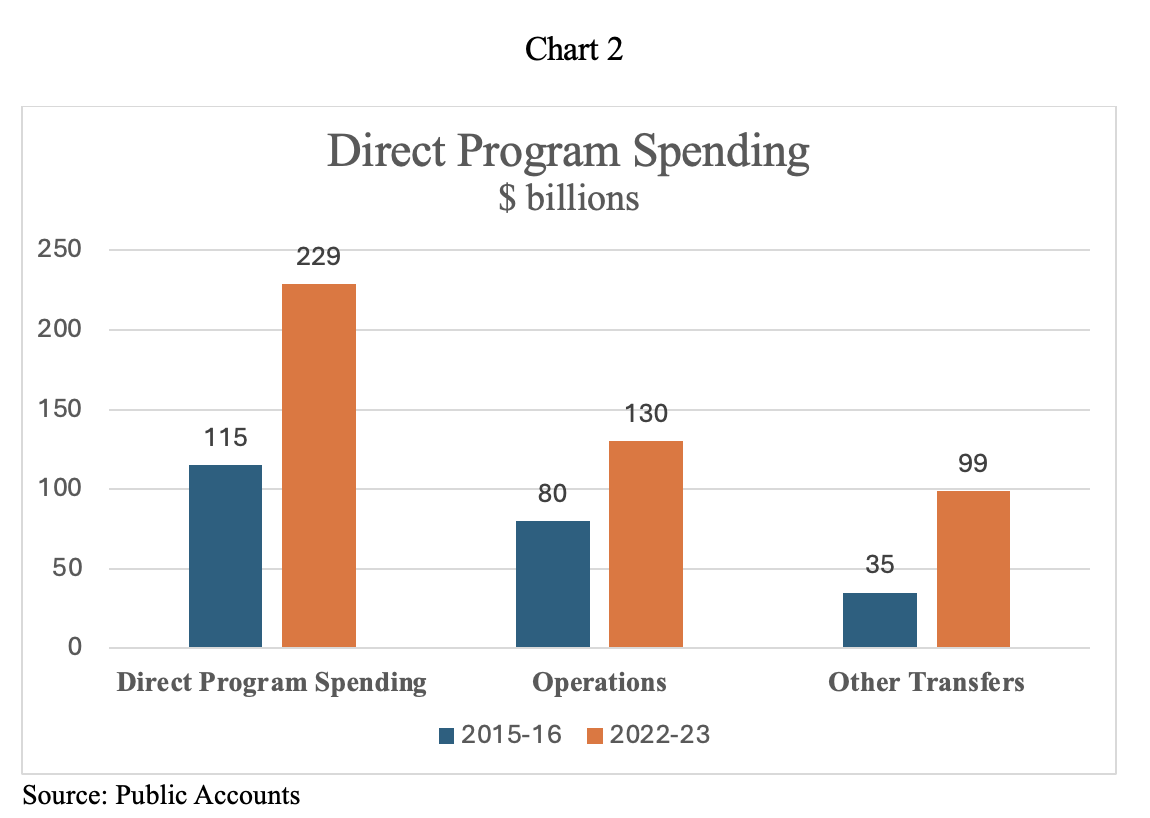

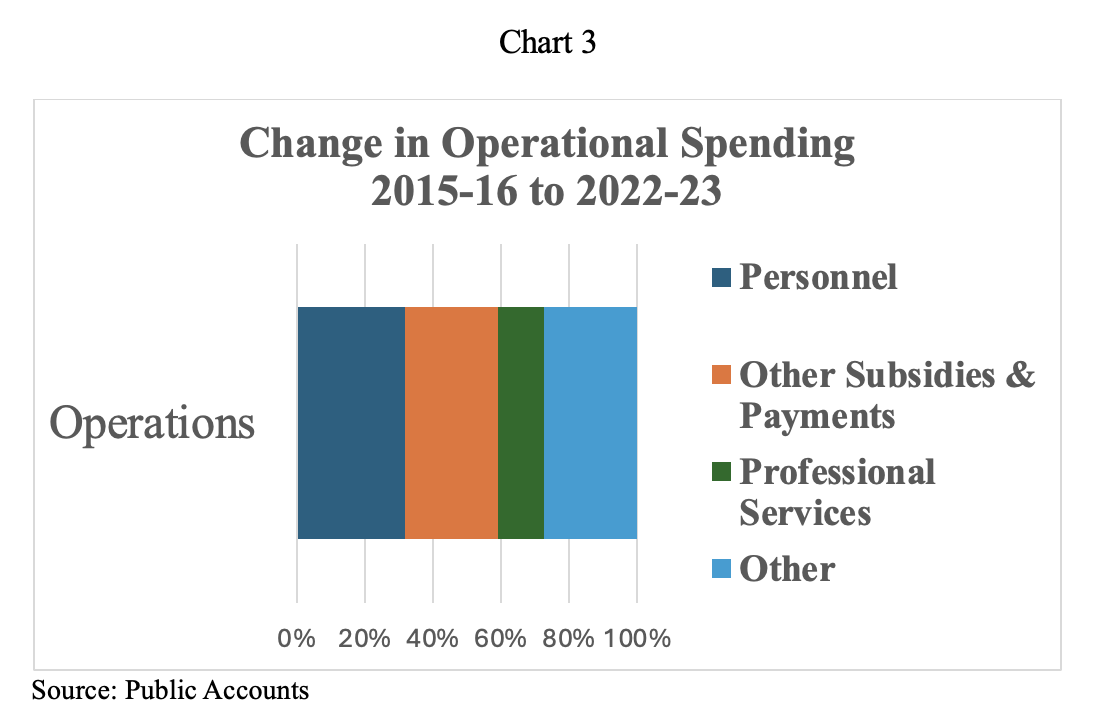

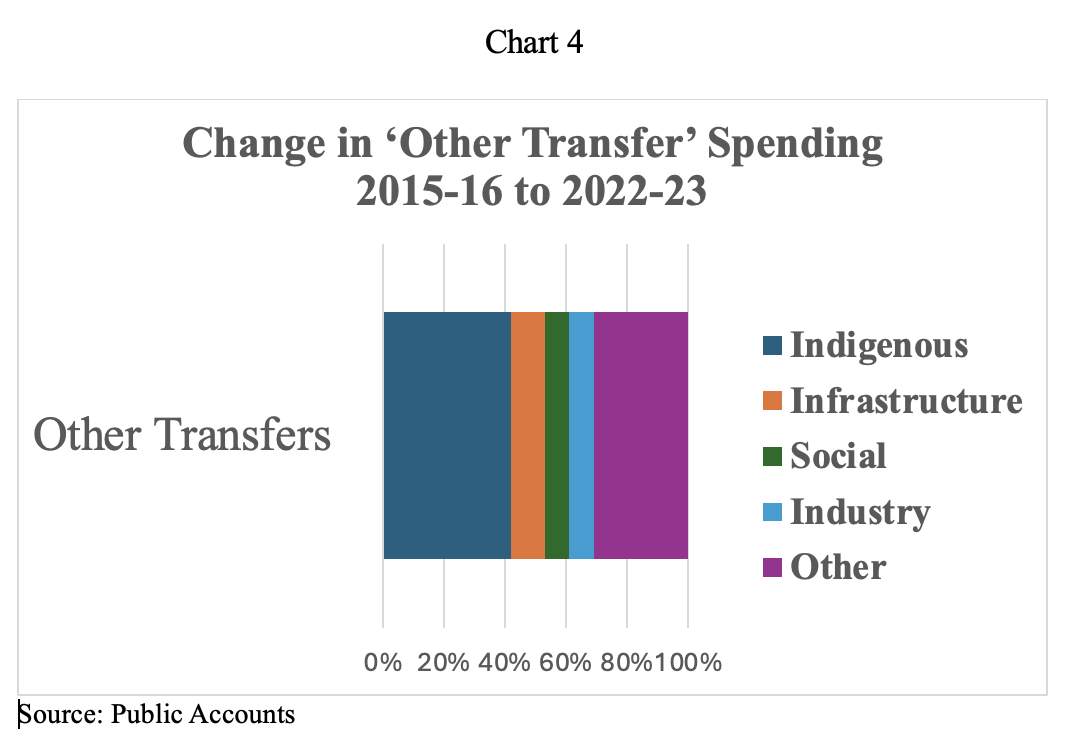

Chart 2 illustrates that direct program spending has doubled since 2015-16 and that the increases are shared between both operations and other transfers. Charts 3 and 4 illustrate that within these components, spending growth is broadly distributed.

The growth of direct program spending implies that the Liberals have fundamentally grown the base of government (relative to transfers – cheque writing – to persons and other levels of government). They have changed both the size and shape of government – bigger and with relatively more direct contact with households and businesses.

Budget 2024 will update the fiscal plan to get back to smaller budgetary deficits. The 2023 Fall Economic Statement indicated the plan was based on holding budgetary revenues constant as a percentage of GDP over the next five years and shrinking program spending.

Table 1 highlights a pivot in the structure of spending over the medium-term planning period. The plan is to substantially shrink direct program spending (relative to GDP) and grow transfers to persons and other levels of government.

Based on spending history since 2015 and the recent pre-budget announcements (including defence spending), is this a credible strategy? How many public servants will need to be laid off to hold operational spending constant in current dollar terms? Is the government prepared to reduce the size of the public service in the lead up to the next election? After significant increases in spending to Indigenous peoples to support children and families, infrastructure and self-government, is the government really prepared to unwind these supports?

In 2023, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Executive Board reiterated that Canada’s fiscal policy must support inflation reduction goals. They suggested a fiscal planning framework, containing a specific debt anchor and a supporting operational rule. The latter could include a spending growth limit rule that would “enhance policy credibility and communication, while helping to assess the trade-offs between spending needs and the pace of consolidation”.

The IMF data set on fiscal rules indicates that many advanced and developing economies have some sort of spending rule. Canada does not.

Do we expect the federal government to announce a spending growth limit rule in Budget 2024? No.

But, should we care about deficit financed spending growth?

What is at stake is the credibility of the government fiscal plan to reduce budgetary deficits? Higher deficits in an era of slow growth and high interest rates compound risks to longer term fiscal sustainability. This means less fiscal room to address the next public health or economic shock. This means higher public debt charges for the next generation of Canadians who will struggle to address climate change and inequality in a less secure world.

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, former Parliamentary Budget Officer and a Contributing Writer for Policy Magazine.

Yasmine Hadid and Hunter Vanderlaan are undergraduate economics students at the University of Ottawa.