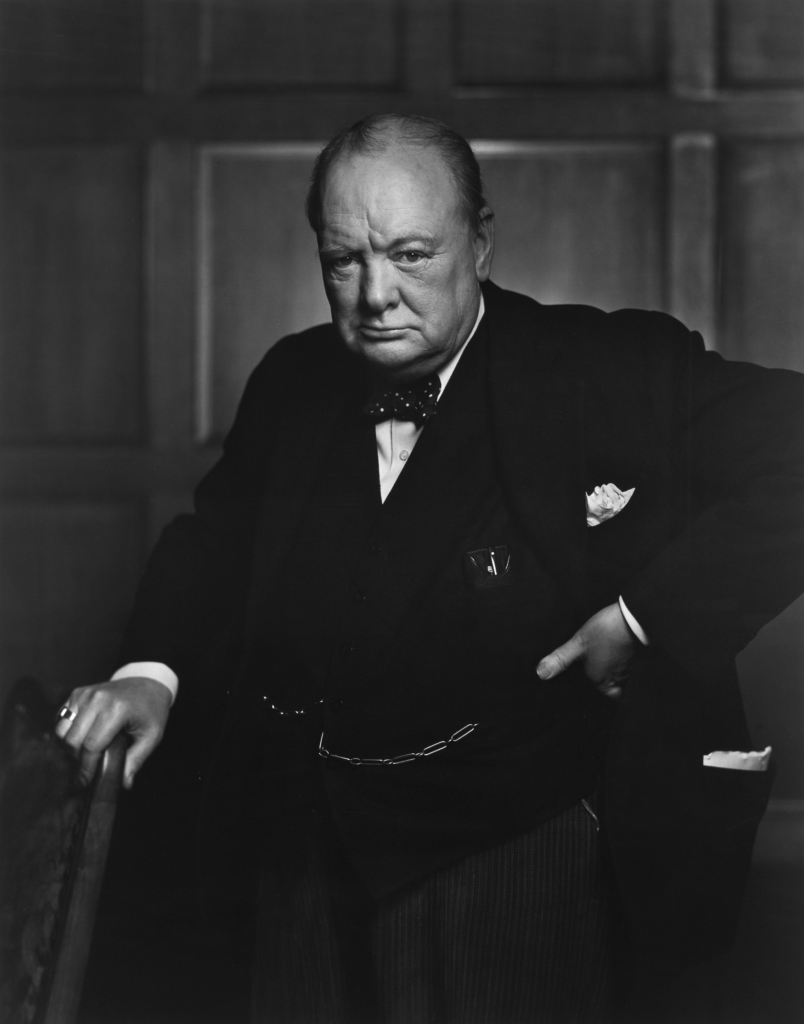

Churchill’s Legacy: “Spending Political Capital in Great Causes for one’s Country”

Brian Mulroney

November 30, 2021

As a long serving Prime Minister, I have spoken often on Churchill, the greatest political leader in modern history.

Tonight I will share with you some of the views I have held and spoken of for many years and which I still hold, unchanged, over the decades.

It is daunting to say anything new or fresh about a man about whom so much has been written, including so much by Sir Winston Churchill himself. There is ample reason why Churchill continues to attract admiration around the world. He was the paragon of leadership during the darkest period of Britain’s history. With unrelenting vigor and tenacity of purpose, he triumphed against all odds and we are all beneficiaries.

No British prime minister, not either Pitt, nor even Disraeli, had such a tumultuous career. His motto was “never despair” and he never did, showing superhuman determination, not only over adversity, but over self-doubt, depression, betrayal, armed combat and mortal, international danger.

Churchill used his unique mastery of the English language to rally his island nation and the Commonwealth, including Canada, against the imminent, seemingly unstoppable threat of Hitler’s Nazis who had swept through Western Europe and were on the verge of enslaving all of the continent.

When Winston Churchill took the helm of the British government in May, 1940, few, very few anywhere had much hope of success – his or theirs. But his indomitable courage, his unbridled optimism, his bristling speeches and his undiluted confidence made him not only the right man at the right time but also the most consequential leader of the last century. That is what we honour tonight.

Churchill was a consummate actor on the world stage. His phenomenal grasp of literature and history, his experience as a journalist and writer, a military officer, a painter and a politician and most of all, his flair for public life imbued his strategic vision and his resolve as a leader under extreme crisis.

He was imaginative and far-sighted in geopolitical matters and, when he made mistakes of judgment, he quickly adjusted for the facts without rancour or embarrassment.

His persistent and ultimately successful overtures to Roosevelt and his complex but necessary alliance with Stalin became the ultimate catalyst for victory. A delicate and essential balance of power and personalities that prevailed over a seemingly invincible foe.

Churchill was a consummate actor on the world stage. His phenomenal grasp of literature and history, his experience as a journalist and writer, a military officer, a painter and a politician and most of all, his flair for public life imbued his strategic vision and his resolve as a leader under extreme crisis.

He used words more powerfully than any weapon. They were in fact his own personal arsenal. And when the war was over and won, he picked up his pen and wrote a personal memoir that stands today as a brilliant record of what happened as witnessed from the catbird seat of government.

His sense of humour rarely deserted him. He once observed “I have often had to eat my words and, on the whole, I have found them to be a nourishing diet”, adding with a smile “I live from mouth to hand”.

Churchill was no stranger to setbacks. He was not always right but, as his ever loyal wife, Clemmie, stated to Asquith in Churchill’s defence: “He has the supreme quality very few of your present or future cabinet possess – the power, imagination and the deadliness to fight Germany”. And that was in 1915!

Churchill’s black dog moments never obscured his focus or his confidence. He made the World War II struggle seem not merely essential for national survival but worthwhile and noble. Despite a spate of initial, military defeats and increasing damage and deprivation on the home front, he evoked persistent cheerfulness among his people. His was “the authentic voice of leadership and defiance.”

He genuinely liked people and they, in turn, liked him.

His common touch with those suffering from the heavy bombing of London is evident from his direct answer to a resident on the scene.

“When are we going to bomb Berlin, Winnie?”. “You leave that to me”, he replied firmly. Not with an equivocal “as soon as we are able” or “not just yet” but with clarity and conviction – the unpredictable magic that was able to transform the despondent misery of disaster into a grimly certain, stepping stone to victory.

“Britain” he said “is a nation with the heart of a lion. I had the luck to be called to give it the roar!”

When Time magazine named him its “man of the half century” in June 1950, they described his role as follows: “Churchill’s chief contribution was to warn of the rocks ahead and to lead the rescue parties. He was not the man who designed the ship; what he did was to launch the life boats. That a free world survived in 1950 with a hope of more progress and less calamity was due in large measure to his exertions.”

After the war, and while serving as Britain’s leader of the opposition, Churchill used the power of his words and his incredible vision to stimulate attention and galvanize action against both the devastation of Europe and the threat of Soviet Russia. His famous “Iron Curtain” speech, orchestrated carefully with the US president in Harry Truman’s home state of Missouri, inspired both the Marshall Plan that saved the economy of Western Europe and the NATO alliance that helpd make Europe secure.

Churchill’s prescience about world affairs and his magical ability to act decisively in the face of overwhelming challenge sparkles throughout his full career. It is the enduring foundation of his proud legacy.

Churchill’s prescience about world affairs and his magical ability to act decisively in the face of overwhelming challenge sparkles throughout his full career. It is the enduring foundation of his proud legacy.

The magnificent oratory of Churchill registers still today. While many examples are well known I cannot resist sharing a few gems to celebrate this occasion:

In May of 1935, he offered a sombre, yet prescient, view of what was to come.

“When the situation was manageable, it was neglected. Now that it is thoroughly out of hand, we apply too late the remedies which then might have effected a cure. Nothing new in this story … until the emergency comes, until self-preservation strikes its jarring gong – these are the features that constitute the endless repetition of history.”

After Munich, and while he was still on the outs with his own government, Churchill stated more trenchantly: “Britain and France had to choose between war and dishonour. They chose dishonour. We shall have war.

On first becoming Prime Minister in May, 1940, he echoed Pitt and defined his objective:

“What is our policy? It is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with the strength that God gave us, to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark, lamentable human catalogue of crime. That is our policy. Our aim is, in one word, victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, however long and hard the road may be for, without victory, there is no survival.”

In June, 1940 after Dunkirk, Churchill promised Parliament:

“We shall not flag or fail. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills. We shall never surrender…..until in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forward to the rescue and liberation of the old.”

Parliamentary diarist Harold Nicolson declared this as “the finest speech I ever heard”.

Assessments of Churchill’s place in history are similarly legendary, and colourful.

Isaiah Berlin captured the essence of Churchill in this way: “a gigantic, historical figure in his own lifetime, superhumanly bold, strongly imaginative, an actor of prodigious power, the saviour of his country, a mythical hero who belongs to legend as much as to reality, the largest human being of our time.”

L. H. Asquith, who had even more direct experience with Churchill, described him as “a wonderful creature, with a curious dash of schoolboy simplicity … and what someone said of genius … a zigzag streak of lightning in the brain.”

Charles de Gaulle, not normally given to compliments about others, wrote in his memoir, “Winston Churchill appeared to me, from one end of the drama to the other, as the great champion of a great enterprise and the great artist of a great history… He was fitted by character to act, take risks, play the part out and out without scruple… He played upon that angelic and diabolical gift to rouse the heavy dough of the English as well as to impress the minds of foreigners”.

The compellingly unforgettable radio voice of Winston Churchill – tinged with courage and sacrifice and heroism – rang out across the 5,000 windswept miles of a young but pulsating Canada and became a clarion call to all to join the battle and they did so in record numbers.

Churchill was never vindictive. His motto was clear but balanced: “In war, resolution. In defeat, defiance. In victory, magnanimity. In peace, goodwill.”

He was a prodigious writer of dynamic power and energy -more than 10 million words in print!- and “a recording angel of striking ruthlessness”.

When he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953, the presenter, Siegfried Siwortz, signaled that “Churchill’s political and literary achievements are of such magnitude that one is tempted to portray him as a Caesar who also had the pen of Cicero. Never before has one of history’s leading figures been so close by virtue of such an outstanding combination…His profound experience is unmistakable. He is the man who himself has been through the fire, taken risks, and withstood extreme pressure. … “He was a rare breed of politician, combining stern resolve and ruthless decision-making with persistent flashes of humanity and humour.”

And, in concluding: “A literary prize is intended to cast lustre over the author but here it is the author who gives lustre to the prize”.

Spanning more than half a century, the statesman we honour this evening had many connections with Canada – what he described fondly as the “Great Dominion”. He visited nine times, more often than to any other country other than the US and France. In his book The Great Dominion, David Dilks observed: “Of no other Commonwealth country did Churchill have such a lifelong knowledge”.

In 1901, at Winnipeg, he first heard the news of Queen Victoria’s death.

After resigning along with the Baldwin government in 1929, he had an extensive vacation that summer in Canada. At Niagara Falls, he regretted that he had not tried to buy a concession there in 1900. When he returned with his daughter again in 1943 en route to Roosevelt’s home at Hyde Park, he was asked whether he noticed any differences from his first visit. “The principle seems to be the same”, Churchill quipped, “the water still falls over”.

Also in 1929, speaking in Montreal, Churchill observed: “How splendid is our common inheritance. It was with a thrill that, after crossing for several days the great wastes of the Atlantic, I landed in a new world, in a new hemisphere, and found myself at home”.

Churchill described more pungently a dinner hosted by the Government of Alberta that summer in High River – “We had cold water and boring speeches…Some kind friend put something better in my tumbler..”

Churchill spoke to Canada’s Parliament on a more solemn occasion in the bleak days of December, 1941. Despite the prevailing mood, he exuded confidence about ultimate victory. Because the French General Weygand had told the last civilian Premier of the Third Republic that “in three weeks Britain will have her neck wrung like a chicken”, Churchill derisively retorted. “Some chicken” …”Some neck”. The gallery and the Parliament in Ottawa erupted in tumultuous applause.

Margaret Lawrence, a noted Canadian author in her own right, wrote about the speech in the magazine Saturday Night: “His voice is a gift from god .. it has come from generations upon generations of culture and sensitivity and authority .. and human warmth … He uses the English of the King James period – powerful, direct, richly intoned. Yet it is simple. It is the English of poets trained to take the shortest route to an idea. Using the most perfect word and the unforgettable, courageously emotional phrases.”

Churchill, as Prime Minister, first met Franklin Roosevelt on the shores of Placentia Bay in Newfoundland in August, 1941, eight years before Newfoundland became part of Canada. (“Meeting Roosevelt”, he declared, was “like uncorking your first bottle of champagne”. He would know.) At that time, they agreed on eight basic clauses that shaped the Atlantic Charter laying the foundation for an alliance that would eventually win the war and also establishing principles for future world order, including notably the “right of all people to choose the form of government under which they live”.

A noble undertaking to be sure and one that resonates poignantly today as we and our allies confront new threats to global peace.

At Quebec City in 1943, and again in 1944, Churchill met with Roosevelt and their respective chiefs of staff to plot the path to victory and give life to the Atlantic Charter and formation of the U.N.

One reason why his remarkable life remains so poignant is that we hear more about dysfunction in democratic government these days than about achievement.

Britain did not stand alone against Nazi Germany. On September 10, 1939, one week following Britain – and two years before America – Canada’s Parliament declared war on Germany. Australia, New Zealand and South Africa joined as well. That was Canada’s first, independent declaration of war and the beginning of the largest combined national effort in our history.

We may not have been directly engaged in shaping the war strategy as our Prime Minister at the time – Mackenzie King – was as cautious and ambiguous as Churchill was bold and decisive, but our contribution and our sacrifice was substantial. From a population of 11 million, over 1 million Canadians – mostly volunteers – served in uniform. Canada fielded the fourth largest air force and the fifth largest naval fleet in the world. We suffered some 100,000 casualties, half of whom were killed in action.

The compellingly unforgettable radio voice of Winston Churchill – tinged with courage and sacrifice and heroism – rang out across the 5,000 windswept miles of a young but pulsating Canada and became a clarion call to all to join the battle and they did so in record numbers.

These were farm boys from the wheat fields of Saskatchewan, coal miners from the pits in Alberta and Nova Scotia, factory and paper mill workers from Ontario and Quebec; doctors, teachers, lawyers, nurses and tradesmen from all parts of Canada – men and women, most of whom had seldom ventured beyond their local community, let alone across a vast ocean. They reflected the rich, regional, ethnic and religious diversity of Canada – our most enduring asset – and they went off to war having heard from Churchill the noblest call of all – Freedom.

Canada was the primary location for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, the largest air force training programme in history. More than 140,000 personnel, including 50,000 pilots were trained, more than half of whom were Canadians who served in the RCAF and the RAF. One out of six RAF Bomber Command groups flying in Europe was Canadian.

Canadian service men and women matured quickly under fire. Their valour and their sacrifices paid dividends in the Battle of Britain, the Atlantic convoys, the invasion of Italy, the D-Day landings in Normandy and in the liberations of France, Belgium and Holland.

Canada’s economic generosity throughout the war and well into the peace was unprecedented. With a population only one-twelfth that of the US, Canada’s financial gifts were one quarter of the total Lend Lease aid from the US. That means they were more than three times greater on a per capita basis. The proportion of defence expenditures given away in terms of free supplies was higher from Canada than from any other country in the world.

In fact “transforming leadership” – leadership that makes a significant difference in the life of a nation – recognizes that political capital is acquired to be spent in great causes for one’s country. That is precisely the lesson from Churchill.

Canada was proud to contribute to this, the noblest cause of all.

Canada heard the voice of Churchill, knew of the hardship and sorrow visited upon his brave island homeland, and responded for King and country with a passion, courage and generosity, replicated only very infrequently in the golden history of great industrialized nations.

After the war, our Prime Minister at the time, Louis St.-Laurent, had welcomed Churchill thus:

“Your voice was the voice of human freedom and became the symbol of the unconquerable spirit of free men and women facing terrific odds. No man living has done more to bring about an association of hearts and minds between your father’s and your mother’s native lands”.

Responding to a toast in Canada in June, 1952, Churchill offered this tribute to Canada: “There is no more spacious and splendid domain open to the activity and genius of free men, with one hand clasping in enduring friendship the US, the other spread across the ocean to Britain and France.

Leadership is not something learned in school. It is innate, an indelible mark of character steeped in integrity, courage, conviction, underscored by the moral imperative to do the right thing. There are many theories of course but what stands out are the lessons from real life – the skills, the choices and the accomplishments of leaders like Churchill whose singular example shines brightly to this day.

One reason why his remarkable life remains so poignant is that we hear more about dysfunction in democratic government these days than about achievement.

But, when you succumb to a gloomy outlook of where we might be heading, keep in mind the rousing oratory and the exceptional talents displayed by Churchill at a time when there were overwhelming grounds for despondency.

The essential attribute for optimism and success now, as before, will be strong, confident, political leadership – that ineffable and sometimes magical quality that sets some men and women apart so that millions will follow as they chart new visions and inspire their citizens to dream big and exciting dreams.

As a contemporary observer noted some years ago: “In a nation ruled by polls and ratings, where even newspapers hire focus groups to see what kind of news readers want, we are losing sight of something we should have learned as teenagers: Just because something is popular doesn’t mean it’s right.”

In fact “transforming leadership” – leadership that makes a significant difference in the life of a nation – recognizes that political capital is acquired to be spent in great causes for one’s country. That is precisely the lesson from Churchill.

If all of us remember that freedom and liberty are the very pillars of our national democracy, we can collectively made a contribution to the wellbeing of mankind that will bring honour, peace and prosperity to all our citizens.

Brian Mulroney, Prime Minister of Canada from 1984-93, spoke to the Churchill Society for the Advancement of Democracy in Toronto, November 30, 2021.