Policy Dispatch: Cité U, the International Student Oasis in the Heart of Paris

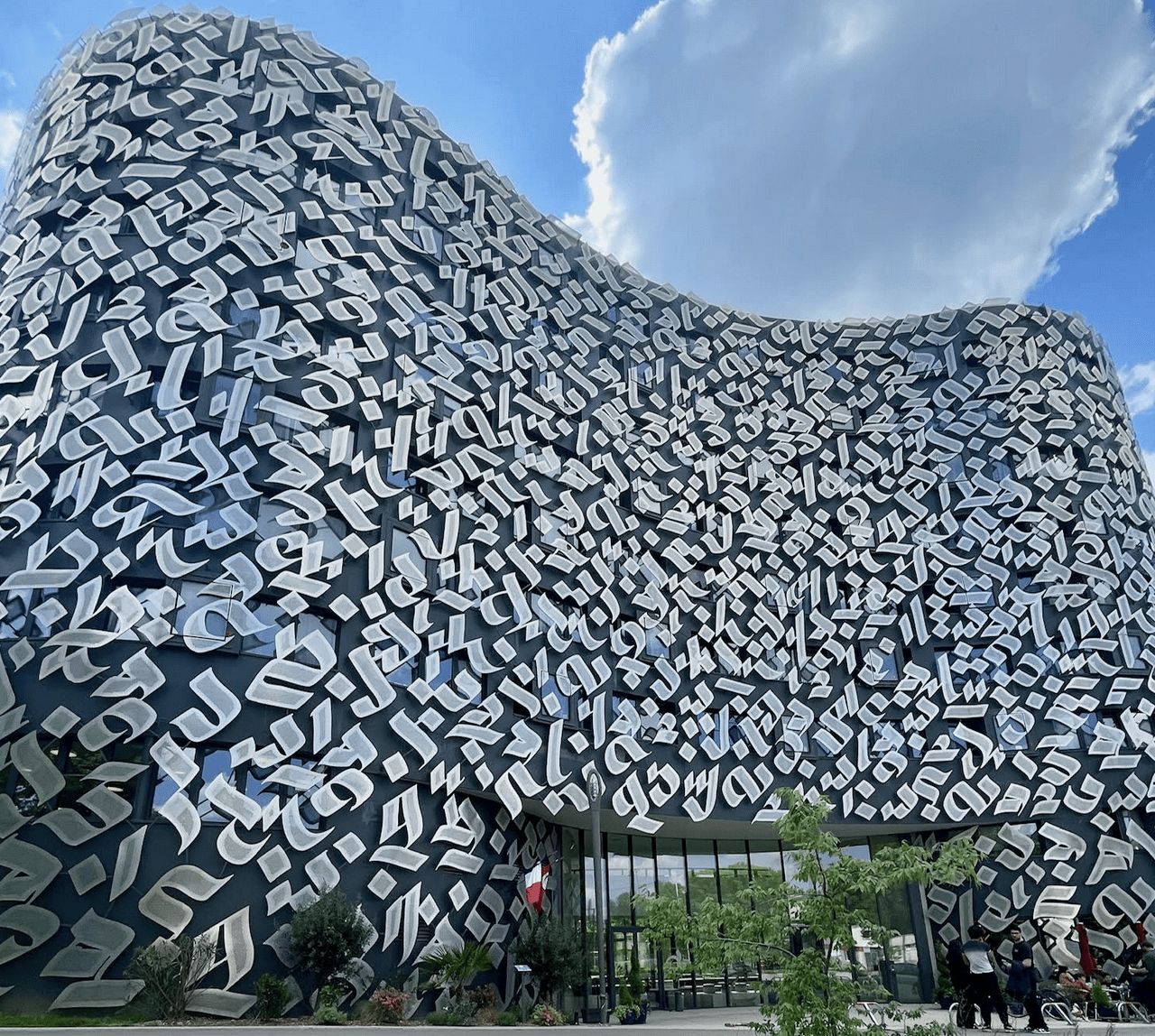

The Maison internationale of the CIUP/Daniel Béland

The Maison internationale of the CIUP/Daniel Béland

By Daniel Béland

May 21, 2025

Three decades ago, I flew to Paris to start my doctoral studies at École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS). I had completed my master’s in sociology at l’Université du Québec à Montréal, and decided to move to Paris to work on the historical development of social policy with Pierre Rosanvallon, a well-known historian, political theorist, and public intellectual.

The Maison de étudiants canadiens at CIUP/Daniel Béland

Instead of staying in a tiny chambre de bonne (maid’s room) or a flat I couldn’t afford, I moved to the Maison des étudiants canadiens (MEC), which is part of the Cité internationale universitaire de Paris (CIUP).

The CIUP, or Cité U was founded in 1925 as an international university campus to foster tolerance and understanding through student exchanges. As early as 1919, André Honnorat, one of the CIUP’s founders, expressed the desire to create “a place where young people from all countries could, at the age where we form lasting friendships, have contacts that allowed them to get to know and appreciate each other.” In a way, when it was created in 1925, the CIUP became some sort of League of Nations for university students enrolled in Parisian universities.

Owned by the universities of Paris and located on a campus of 84 wooded acres in the city’s southern 14th arrondissement just inside the périphérique and adjacent to the Parc Montsouris, the CIUP includes 45 foundation-funded residences and national “houses” welcoming 12,000 students and academics. Its former residents include the filmmaker Costa-Gavras, the conductor Seiji Ozawa, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, who arrived as strangers and fatefully met at a study session on Leibniz in Sartre’s room in 1929. Canadians who have lived in the MEC residence include Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Jacques Parizeau, and Paul Émile Borduas.

In the MEC I encountered a mix of Canadian and, to a lesser extent, international residents. While most Canadians were francophones from Quebec, people from other parts of the country, both anglophones and francophones, were well represented. On the international side, I interacted with students from countries as different as Belgium, Mexico, and the UK. I also met students from other residences at cultural events and social activities and at the Resto U, the large cafeteria located in the splendid Maison internationale.

Habib Bourguiba Hall, one of two Tunisian student residences/Daniel Béland

Habib Bourguiba Hall, one of two Tunisian student residences/Daniel Béland

During a recent visit to Paris, I returned to the CIUP with an old Parisian friend to attend a chamber music concert at the Maison Heinrich Heine, Germany’s residence. Walking on the grounds of the CIUP is idyllic, not only because of its many green spaces, but because of the architectural diversity of its residences, some conceived by great architects like Le Corbusier, in the case of the Swiss pavilion, and in collaboration with the Brazilian architect Lucio Costa, the Maison du Brésil. Many residences also serve as cultural centres for the country they represent, as they organize talks, concerts, and art exhibits. It is a fascinating place to visit but it is also a great place to live for both French and international students who struggle to find a flat in one of the most expensive cities in Europe.

This year, as the CIUP celebrates its centennial, looking back at its history offers lessons for those in Canada and elsewhere who might want to address the urgent challenge of creating affordable housing spaces for students while freeing up space in other places for different segments of the population. Importantly, helping students find a place to stay in France’s crowded capital was only one of the three main objectives of the CIUP’s founders. By locating the student residences in a large green space freely accessible to everyone, they wanted to contribute to what was known at the time as “public hygiene” (i.e. public health). At the same time, while explicitly addressing housing and public health challenges, the CIUP was the product of a humanistic and pacifist attempt to foster dialogue and mutual understanding among young people from different countries not long after the end of World War I.

Although there is something utopian about the internationalist vision articulated by the CIUP’s founders a century ago, as someone who spent more than two years living there much more recently, I can say that it does bring students from different countries together in a way that helps them build lasting friendships, which is a great thing, both academically and socially. A philanthropic entity since its creation, the CIUP’s setting, design and mission fostered cross-cultural connection in an era long before the internet. That spirit has endured, making the physical CIUP campus a melting pot of nationalities, languages and cultures within a city whose residents also appreciate it as an urban oasis.

Montreal’s Royal Victoria Hospital legacy site/Jean Gagnon via Wikimedia

Can something like the CIUP be created in Canadian cities in the aftermath of an ongoing housing crisis that is creating major challenges for students, both domestic and foreign? In 2021, three Montreal colleagues ‑ Université de Montréal political scientist Frédéric Mérand, former Senate parliamentary affairs director Jérome Lussier and political consultant Nicolas-Dominic Audet ‑ presented a proposal citing the CIUP and other international university residential centres in Chicago and New York to support the creation of a similar a bilingual, international, and interuniversity Cité universitaire internationale de Montréal on the site of the old Royal Victoria hospital on Mount Royal.Time will tell whether their idea will become reality, but it would complement nicely McGill’s New Vic project.

Beyond Montreal, the CIUP could help inform similar ideas of international student residences in other large Canadian cities such as Toronto and Vancouver, in which the housing crisis is even more acute than in Quebec’s metropolis. Regardless of whether they would take a philanthropic, a public-private, or a purely public form, the multiplication of international student residences, which already exist on Canadian campuses like the University of Alberta, could help address the housing crisis while fostering global dialogue.

Considering that international students have sometimes become scapegoats for the housing crisis, such projects could also help our universities make a stronger case for the continued, significant presence of these students in Canada, a presence that is vital on several levels, including the strengthening of our economy, which is a key priority of both the federal and provincial governments. This is especially the case now that the policies and rhetoric of the second Trump administration are making our southern neighbour less attractive to international students and researchers, creating clear recruitment opportunities for Canadian universities and employers.

Earlier this spring, when I left the CIUP after a wonderful concert, I was not thinking about economic realities but about all the fellow students I had met there 30 years ago and who helped me better understand both the world and my place within it.

Although there is a strong economic rationale for welcoming international students to Canada and finding affordable places for them to stay, the humanist ideal of international dialogue the CIUP’s founders had in mind a century ago is also worth perpetuating, especially in an era when protectionism and xenophobia have become powerful tools in the hands of populist politicians who seek to “divide and conquer” instead of bringing people, especially young people, together.

Daniel Béland is professor of political science and director (on leave) of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada at McGill University.