Continental Divide

By Douglas Porter

April 05, 2024

We have been going on, and on, for nearly a year about the growing divergence between the North American economies—a surprising/amazingly resilient U.S. set against a struggling Canada. Just as there were some indications the gap may be narrowing in early 2024, the March employment reports put an exclamation point on the wedge. Last month saw the U.S. churn out yet another chart-topping payroll gain of 303,000, clipping the unemployment rate to 3.8%. In the meantime, Canada saw a full eclipse of the jobs, with a 2,200 drop, sending the unemployment rate up 3 ticks to 6.1%. That 2.3 ppt divide between the jobless rates is at the very upper end of the range over the past twenty years, aside from the madness of the pandemic. This simply reinforces our conviction that the Bank of Canada will be leading the Fed on the rate-cut front, just as it led on the way up the hill two years ago.

Markets have been steadily reeling back expectations of Fed rate cuts almost since the year began, and this week’s events pulled the string a bit further. While Chair Powell sent soothing tones in a Wednesday speech, suggesting the bigger picture had not changed, the freshly converted uber-hawk Kashkari opined that perhaps no rate cuts were needed at all this year. With job growth still chugging along, GDP on track for at least a 2% advance in Q1, the factory PMI pushing back above 50, and now oil prices at $87 threatening to lift headline inflation again, it’s not obvious that he’s out of line. We remain entirely comfortable with our call that the Fed will wait until July to start the rate cuts. After bravely staring down fading prospects of rate relief through Q1, equities showed a flicker of concern this week, with the S&P 500 dropping roughly 1% from last Thursday’s record high.

It is a very different post-jobs conversation in Canada. Full disclosure, there has been some wavering on our call for a June cut by the Bank of Canada, especially in light of a run of surprisingly sturdy GDP growth to start 2024, as well as solid financial markets, a stabilizing housing market, and fading Fed rate cut prospects. Standing against that, the two main pillars of support for our relatively dovish call on the BoC were low inflation and rising unemployment. The past two CPI reports have been stunningly helpful, with ex-shelter inflation dropping to a mere 1.3% y/y. But the snapback in oil and sticky wage growth of around 5% could frustrate further progress, and threaten to keep inflation expectations firm.

Against that backdrop, the steep rise in the unemployment rate last month is an important development, as it suggests that wage trends will eventually ebb. In fact, with the jobless rate pushing above 6%, one can make the case that the labour market is no longer tight in Canada. One rule of thumb we watch is the year-over-year change in the number of unemployed people. Over the past 40 years, in both Canada and the U.S., any time it has risen by 25% or more, the economy has been in recession (Chart 1). (Note that Canada didn’t quite get there in the 2000/01 cycle, and that period was not judged to be a recession by the semi-official arbiters of such.) The back-up in March left the number of unemployed Canadians up 23% y/y, right at the edge. In stark contrast, the same metric shows a rise of less than 10% for the U.S. economy, reinforcing North America’s wide divergence. A rather obvious rejoinder is that the surge in Canada is driven by smoking population trends, and can’t be readily compared with the past.

We won’t need to wait long to find out exactly how the Bank of Canada views these conflicting trends, with the rate decision and MPR next Wednesday. While there’s not much debate that the Bank will hold rates steady again at 5%, there’s a lot of debate over just how dovish they will sound. Even with a moderate upgrade in the 2024 growth outlook (the BoC was previously at 0.8%, we’re now at 1.2%), inflation is nicely tracking below their estimate of 3.2% for Q1 (likely 2.9%), so we look for the Bank to open the door a crack for coming rate cuts.

Just prior to the BoC announcement, the U.S. CPI is likely to flag a small warning on the impact of higher oil prices, with headline inflation rising a couple ticks to 3.4%, even as core is expected to dip to 3.7% (both on monthly increases of 0.3%). That energy-led uptick could be mirrored in Canada’s CPI the following week, albeit holding below 3%. For both the job market and inflation, Canada is showing some separation from the U.S., and we suspect that will drive a small separation between BoC and Fed rate policy in coming months.

Besides sticky wages, one possible reason for the Bank of Canada to hold off on rate cuts a little longer is a fear of stoking a smoldering housing fire. The early read on March home sales and prices from the larger cities pointed to stability and a rough balance in many markets, but there is a widespread sense that there is plenty of pent-up demand. This week brought a slew of announcements to support building, but these supply measures will take years to bear fruit. Meantime, CMHC expects new building to actually fade for a third year in a row to below 225,000 units in 2024 (we’re at 240,000), and for prices to start heading higher in the next few years.

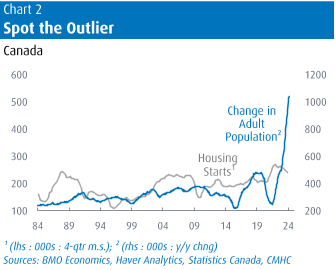

The minor fade in new construction reflects the reality of a softer market in the past few years, defying the widespread calls for a dramatic increase in supply—which was simply never going to happen. Residential construction already consumes almost 8% of nominal GDP, versus a long-run average of 6%, and now almost as much as business investment in M&E and structures, which is now 8.5% versus a long-run norm of 10.6%. Yet, the demand for more, more, more supply is never-ending. Even The Economist magazine got into the act this week, by suggesting that the core of the housing affordability problem is “decades of sluggish housing construction”. To that hogwash, we submit Chart 2, which shows that starts were for decades actually pretty much right in line with adult population growth (on a roughly 1 for 2 basis, with a little bit of extra starts). What changed radically in recent years, completely upsetting the fine balance?

Only now armed with the knowledge that the adult population was going to spike by more than 2 million people in the space of three years could anyone reasonably suggest that building had been sluggish “for decades”. Recall, that just ten years ago, the conventional wisdom was that Canada, and specifically Toronto, was headed for a housing crash due to rampant overbuilding.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.