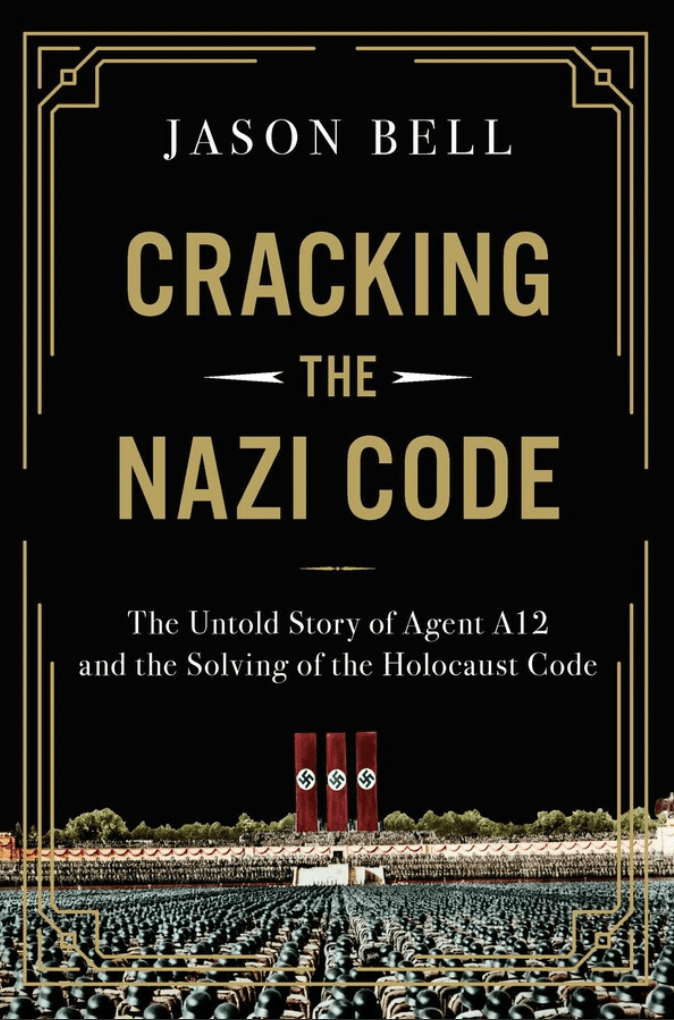

‘Cracking the Nazi Code’: The Canadian Who Warned the World

Cracking the Nazi Code: The Untold Story of Canada’s Greatest Spy

By Jason Bell

Harper Collins/September 2023

Reviewed by Robin V. Sears

December 31, 2023

One of the stalest cliches about Canadian culture is that it sits suspended somewhere between Europe and America. Overused it may be, but it is more than a little bit true. Still, there are a number of areas where we resemble almost no one else on the planet. One is in our near-complete disinterest in, and deep misunderstanding of, the nature and value of intelligence — its role, its ability to help manage future risks, and its unique international policy guidance.

We don’t like spying, we don’t care if our intelligence agencies are any good, and we would be indifferent, if not inwardly proud, if any politician were to warn that our intelligence gathering, analysis and policy role were by far the worst in the G7. Like almost every other Canadian, I never knew that Global Affairs had launched its own internal spy agency — the Global Security Reporting Program — until they were revealed as unhelpful players in the Two Michaels case.

So, here’s a head-spinning revelation for you.

Did you know that it was a Canadian spying for MI6 who first revealed to the world Adolf Hitler’s plan for the Holocaust 20 years before it was diabolically implemented? His name was Winthrop Bell, he was known as agent A12, and the list of his intelligence and political coups is simply extraordinary. Even if his pointed 1919 warning to his intelligence and political superiors about the gathering miasma of Nazism more than a decade before the Nazis called themselves Nazis went catastrophically un-heeded, Winthrop Bell’s role in defending democracy from Hitler’s orgy of vindictive domination remains a stunning series of operational accomplishments.

Winthrop Bell, undated/Mount Allison University archives

Winthrop Bell, undated/Mount Allison University archives

Bell, the son of a Nova Scotia fish processing family, studied and taught at the University of Göttingen, spoke fluent German and had broad and deep networks in the country. A progressive in the Canadian sense, he abhorred what he saw as the German aristocracy beginning to privately fund anti-Semitic gangs only months after the end of World War I. He devoted much of his intelligence career to attempting, over several decades, to crush the Nazis.

For a century, his name was not prominent in Canadian histories, and there are no monuments to his achievements at his alma mater, Mount Allison in New Brunswick. But it was Mt. Al that, after years of refusal, finally opened the door to Bell’s extensive papers, which were held in its archives.

The man who finally overcame their resistance is a fellow New Brunswick academic, Jason Bell (no relation). With the help of British and German sources and building on what he discovered in Winthrop Bell’s papers — which were replete with letters, memos, and accounts of his exceedingly risky adventures — Jason Bell assembled the puzzle of the spy who might have been branded “intrepid” two decades before Winnipeg-born William Stevenson established the wartime British Security Coordination spy service. Prof. Bell then produced Cracking the Nazi Code: The Untold Story of Canada’s Greatest Spy. As an intelligence-history junkie, I have consumed dozens of similar tell-all bios and memoirs of spies and their agencies. They are often underwhelming as they have had little access to source materials.

Cracking the Nazi Code is full of detailed accounts, often written by Winthrop Bell himself. And Jason Bell’s great ability as a storyteller, as well as his skill at threading distant people and events into a compelling narrative, are what make this such a fine book. I would describe it as one of the best ever written on the intelligence history of the first half of the 20th century, and without doubt the finest on Canadian intelligence history, though that is admittedly a low bar.

Winthrop Bell’s role in defending democracy from Hitler’s orgy of vindictive domination remains a stunning series of operational accomplishments.

The author is so good at slowly building tension around the unfolding of events that it reads like a spy thriller. While I’m sparing with spoilers, here is just one covert achievement that Winthrop Bell was credited with by leaders of the secret world in the UK and the U.S.:

The disastrous Treaty of Versailles, which Margaret MacMillan so magisterially dissected in Paris 1919, almost collapsed several times over its many months of squabbling. One of the final intractable issues to be resolved was the dispute between Germany and Poland over the city of Danzig (now Gdansk) in Upper Silesia.

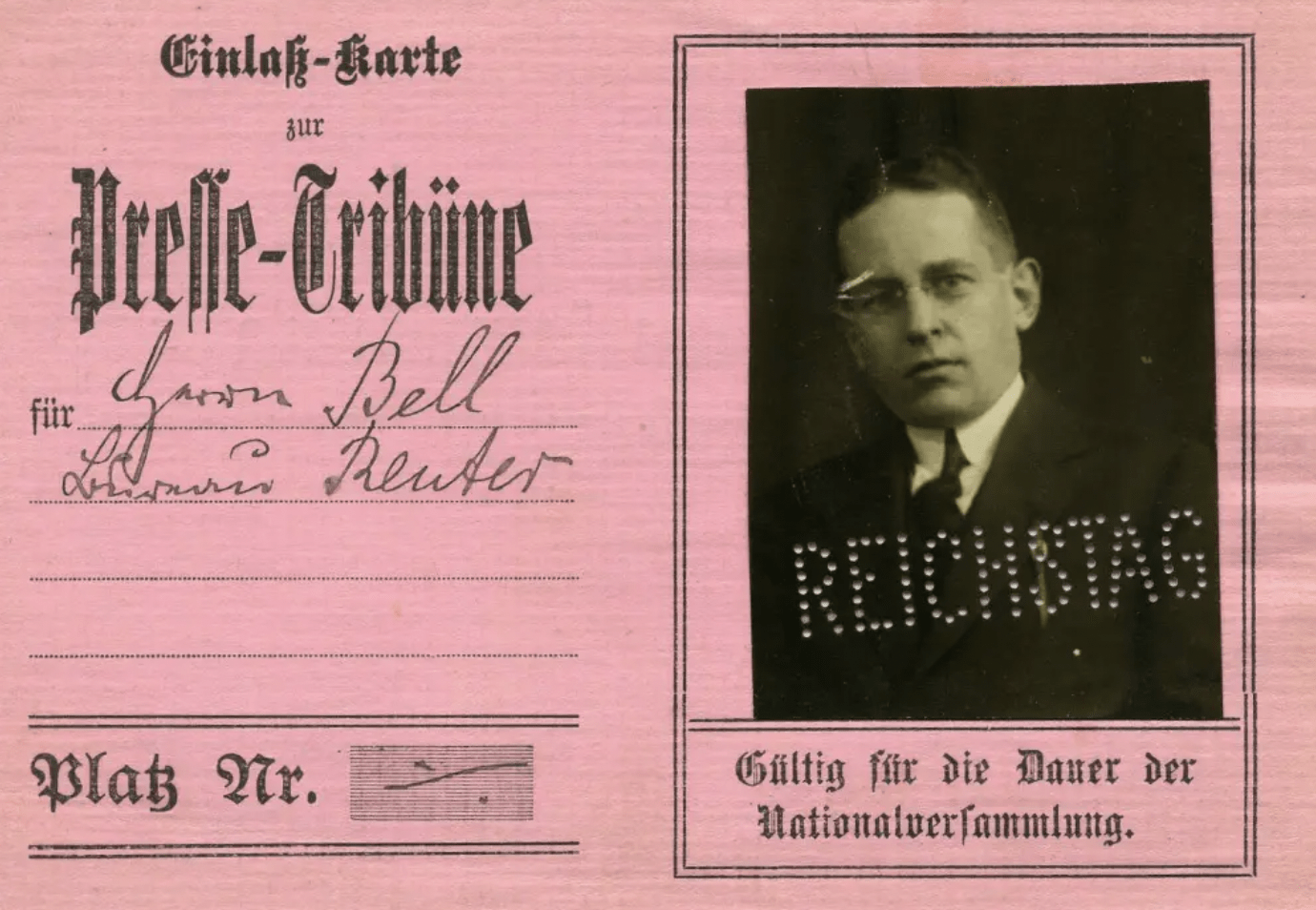

Gdansk — including the shipyard that made it and the Solidarność trade union movement famous six decades later — was a key trading port, strategically located. It had been in several hands over its centuries, but most recently as of 1919 had been part of Poland for more than a century. Our master spy knew several of the players, knew how deep was their obduracy, but accepted being handed the file under cover as a Reuters correspondent to persuade the two sides to come to a compromise. He was, surprisingly, asked to appeal to the British public in a series of newspaper opinion pieces. He did. He eloquently and passionately argued that giving Danzig to the Poles would violate the Treaty’s commitment to national self-determination and probably re-ignite conflict on the shared border.

Winthrop Bell’s 1919 Reichstag press credentials/Mount Allison University

Winthrop Bell’s 1919 Reichstag press credentials/Mount Allison University

Meanwhile, an increasingly bloody conflict was already breaking out between gangs from either side. Bell travelled to meet with the German High Command in Silesia. They warned that they were quickly losing their ability to control vigilante violence.

Bell, as the author details, then sat “just offstage”, whispering compromise counsel, in Versailles, in London, and to the two hostile nations. Out of these secret contacts, and his shared intelligence, emerged the agreement to admit Germany to the League of Nations, allowing the League to be named as the supervisor of a peace in Upper Silesia, later known as the Polish or Danzig Corridor. His was the key that unlocked Germany’s resistance to signing.

The details of the occupational hazards of Bell’s endeavour — managing so many relationships, keeping them secret from each other, keeping track of what you heard from whom and to whom you’d shared it with under very heavy time pressures, never putting a foot wrong or being uncovered — are mind-boggling. Successfully planting the seeds of a peace that would last two decades — equally breathtaking. While not giving the story away, permit me to simply cite the gist of two more extraordinary contributions: The 1919 projection, with details, names and dates of the Holocaust to come, and the Marshall Plan.

Finishing and reflecting on the amazing revelations that Jason Bell was able to document one is left with sad “What ifs?” What if the Allied powers had listened to Agent A12, and his description of the slide to fascism beginning with the near-starvation the victors had imposed on Germany? What if his political bosses had taken on advisement the importance of a group of rich German families bankrolling Hitler as far back as the early 1920s?

And the saddest missed opportunity of all was, of course, not listening to — and believing — A12 on the Adolf Hitler’s determination to begin not just the elimination of Jews around the world, but later those of other races and ethnicities. Perhaps today’s timid response to the explosion of anti-Semitism gives us a clue: too many leaders were unwilling to spend any political capital defending the Jewish people, either then or now, with predictable results for the world.

Policy Contributing Writer Robin V. Sears is a longtime political strategist and former diplomat.