Cracks in the Foundation

Douglas Porter

April 6, 2023

The biggest economic theme so far in 2023 is one of surprising resiliency among most of the major regions, even in the face of a variety of emerging threats and the rapid reset in interest rates from a year ago. For example, even as the IMF warns about the potential cost of “friend-shoring”, it is still looking for 2.9% global growth this year, an upgrade from last fall’s view. Our call for GDP growth in both the U.S. and Canada for this year has been bumped up to 1% from zero at the start of 2023, mostly owing to a sturdy first quarter performance. But perhaps the biggest upgrade has been in the European economies, where mild weather and sliding energy prices helped avert the worst-case scenario; we are now looking for modest 0.6% growth in the Euro Area this year versus earlier expectations in late 2022 of an outright decline. And the persistent growth has kept job markets tight and central banks mostly in tightening mode.

In fact, economies had held up so well this year that some were openly pondering the possibility of not just a soft landing but no landing whatsoever. The banking sector stress of the past month silenced such talk for a while. And, in more recent days, the early batch of data for March is beginning to flash some clearer signs of underlying cooling, especially in the U.S.. (Obligatory disclaimer: Statutory holiday deadlines dictate that this is penned a day before the payroll report, which could send a very different signal. But the weight of evidence ahead of that key release is pointing weaker.) Prior to payrolls, some of the most notable signs of softer activity this week included:

- The ISM releases took a much bigger step down last month than expected, with both manufacturing (46.3) and services (51.2) at levels bordering on respective recession terrain.

- Job openings finally dropped below the 10 million mark in the prior month.

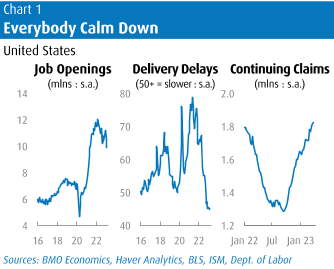

- The trend in jobless claims is now rising, especially after some big upward revisions (Chart 1).

- The ADP saw a notable cooling in job growth (145,000).

- Auto sales took a step back to below 15 million units.

- Construction and factory orders dipped in February, while the trade deficit widened.

- Mortgage applications fell 4.1% in the latest week, and remain at a low ebb despite the steep drop in mortgage rates in the past month.

- Arguably, even OPEC+’s surprise decision to cut oil production by more than 1 million bpd can be construed as a sign of weakness—demand has been softer than expected, prompting the defensive measure to shore up crude.

Markets have taken this inch of bad news for growth and run with it for a mile, further slicing yields across the curve to levels not seen since late last summer. Two-year Treasury yields fell almost 30 bps this week in the lead-up to jobs to just below 3.8%, or down more than 130 bps from their highs of a month ago. The rally at the longer end was nearly as ferocious, with 10s falling almost 20 bps in four days to below 3.3%, the lowest since around Labour Day and down 80 bps in a month. What was a bit different amid this batch of economic softness and furious bond rally was that stocks did not enjoy the ride. Put another way, bad economic news actually was treated as bad news for equities. Bigger picture, stocks have recovered nicely from the bank squall, but sagged slightly on the week amid gathering signs of softer growth.

Markets have taken this inch of bad news for growth and run with it for a mile, further slicing yields across the curve to levels not seen since late last summer. Two-year Treasury yields fell almost 30 bps this week in the lead-up to jobs to just below 3.8%, or down more than 130 bps from their highs of a month ago. The rally at the longer end was nearly as ferocious, with 10s falling almost 20 bps in four days to below 3.3%, the lowest since around Labour Day and down 80 bps in a month. What was a bit different amid this batch of economic softness and furious bond rally was that stocks did not enjoy the ride. Put another way, bad economic news actually was treated as bad news for equities. Bigger picture, stocks have recovered nicely from the bank squall, but sagged slightly on the week amid gathering signs of softer growth.

But before concluding that all slowing road signs lead directly to recession, we would make a few points. First, some of the cooling in March represents a natural pullback from shocking and likely weather-related strength in the first two months of the year. Second, any signs of weakness in durable goods—whether it’s factory production, spending, or orders—must be put in the context of the extraordinary strength in this space during the pandemic. We are now seeing the natural swing back to spending on services and away from goods. A great example of this divergence between goods and services is courtesy of China, where the private sector PMI for factories sagged to just 50.0 in March, even as the services index hit a 2.5-year high of 57.8.

As a sidebar, this also helps explain the dramatic improvement in supply chains (see middle panel in the Chart as a prime example), which we always believed was more an issue of a tidal wave of demand for goods, and less so an actual supply problem. One wrench in the argument that much of the weakness we are now seeing is due to the goods-to-services transition was the surprisingly soft U.S. services ISM. But even it can be partly explained by a huge drop in supplier delivery delays, which account for a quarter of the index. The important business activity and employment sub-components were still sturdy in March.

Having duly defended the economy’s honour, we are left with the reality that our official call is for U.S. GDP to stumble in Q2 into a small decline after 2.0% growth in Q1. Some inevitable tightening in credit, along with the full weight of the 475 bps of rate hikes in the past year, will more fully dig into activity in coming months. And the sag in March is likely a prelude to that chillier growth backdrop. A key question is whether that significant slowing will be so readily apparent by the Fed’s next meeting in early May, thereby pushing them to pause. We lean to the answer being no (i.e., one more 25 bp hike to cap off the cycle), but markets still see it as a coin flip.

There’s much less drama over the Bank of Canada’s intentions. Having led the way to the sidelines, the widespread view is that the global banking sector strains will have locked them there. And a pair of much milder than expected CPI releases to start the year have reinforced the conviction that the Bank is done tightening for the cycle. Yet the economy has a nasty habit of intruding on that neat story with persistent signs of strength. While Canada did not see quite the same volume of early data for March this week, it made up for it in quality. Top of the deck was yet another show of strength from employment, including a 34,700 job gain, another 5.0% jobless rate, and a 0.4% rise in total hours worked (the latter rose at a 5% annualized pace for all of Q1). The rollicking job gains suggest that our upsized estimate for Q1 GDP of 2.5% may still be on the light side of reality.

Given Canada’s fiery population growth, the Bank of Canada is probably more than willing to swallow strong job increases. After all, the unemployment rate has basically held steady since last June. But two items this week may cause them a bit more angst on the inflation outlook. First, wage growth held at uncomfortably strong levels in March at 5.3%, which is likely to be well north of inflation for that month (we have pencilled in something in the low 4% range). Second, there are signs that the housing sector may be stirring after the past year’s pounding. Sales and prices look to have nudged up from weak levels in some of the major cities in March, or exactly when the Bank moved to the sidelines. Make no mistake, activity is still lacklustre, but if even the most interest-sensitive component of the economy is now showing a brave face, just how tight is policy really?

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.