Ding Dong, Inflation’s Dead?

Douglas Porter

November 17, 2023

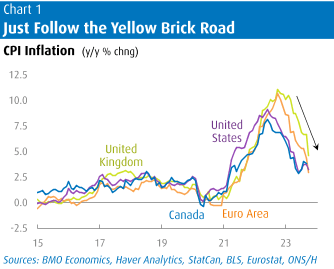

Markets were back in rally mode this week after the briefest of lulls, finding fresh fuel from a series of favourable inflation results. The topper was the mild U.S. October CPI reading, with the flat headline the second-softest result of the past three years, and low enough to carve the annual inflation rate by half a point to 3.2%—the lowest since March 2021. Core is still stubborn at 4.0% but, even there, the six-month trend has calmed to a manageable 3.2% annualized pace. Even Britain, which has had the stickiest prices, saw its rate slashed by more than 2 ppts to 4.6%, while the Euro Area confirmed its October result of a mild 2.9% pace. All of these headline inflation rates are now down by 6 percentage points or more from the multi-decade highs reached last year. Canada’s October CPI report on Tuesday is also expected to see a minimal monthly rise and a hefty drop in the headline to just above 3%, down 5 ppts from last year’s peak.

Suffice it to say that in the post-war era, the advanced economies have never before been able to cut inflation so heavily and so quickly in the absence of a full-blown recession. Meantime, the renewed drop in oil prices to around $75 and a near-two-year low on wholesale gasoline prices points to further near-term relief. Combined with some softer U.S. economic data this week—a dip in October retail sales, a back-up in jobless claims, and a sag in industrial production—and yields took a big step down, with 2s and 10s falling nearly 20 bps, and 5s dropping even further. This fired up equities, with the MSCI World index now up 8% from the lows reached just three weeks ago, and up almost 13% for all of 2023.

Suffice it to say that in the post-war era, the advanced economies have never before been able to cut inflation so heavily and so quickly in the absence of a full-blown recession. Meantime, the renewed drop in oil prices to around $75 and a near-two-year low on wholesale gasoline prices points to further near-term relief. Combined with some softer U.S. economic data this week—a dip in October retail sales, a back-up in jobless claims, and a sag in industrial production—and yields took a big step down, with 2s and 10s falling nearly 20 bps, and 5s dropping even further. This fired up equities, with the MSCI World index now up 8% from the lows reached just three weeks ago, and up almost 13% for all of 2023.

What has caused this seeming immaculate disinflation? And, perhaps more importantly, can it continue so that inflation is back within central banks’ comfort zones? To address those crucial questions, we turn to the deep and enduring wisdom of the Wizard of Oz, 84 years young this year:

“I’m melting”: Supply chain snarls were widely cited as one of the main causes of the initial burst of inflation, with a wide variety of durable goods prices flaring higher in 2021/22. Notably, vehicles, furniture, appliances, and electronics were all impacted by the chip shortage or other snags. We have long argued that the supply chain issues were as much a case of over-stimulated demand as a supply story, but whatever the cause, the issue has melted away. The New York Fed’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index was at its lowest level in its 26-year history in November, a complete reversal from its peak of exactly two years ago. On cue, there is now no inflation in goods prices—U.S. core goods were unchanged from a year ago, versus double-digit readings as recently as early 2022.

“Surrender OPEC”: Energy prices were another major early source of the burst of inflation, with OPEC’s disciplined production cuts and the war in Ukraine adding to the upswing in oil & gas. However, concerns over global demand along with a full recovery in U.S. oil production (to a new all-time high of over 13 million bpd) have tamed energy costs. At their fiercest, U.S. gasoline prices were up almost 60% y/y in mid-2022; now, they’re down about 10% from a year ago. Meantime, natural gas prices seem to have settled in around $3/mmbtu, or less than half of last year’s average. While we are anticipating moderately firmer prices for both oil and gas next year, the point is that energy isn’t a major inflation driver at this point—despite the best efforts of OPEC+.

“We’re not in Kansas anymore”: Food inflation was the third leg of the stool in the initial inflation burst, and it had the longest tail. However, there is increasing evidence that food inflation is finally calming, if not set to go into outright reverse. Even with an ongoing drought in the North American plains (yes, including the key wheat growing state of Kansas), this year’s global grain crop looks to be a bit better than average. Major indices of agricultural commodity prices are back to pre-Ukraine invasion levels. After peaking at 13.5% y/y in August 2022, U.S. grocery price inflation has eased all the way to a quiet 2.1%. In Canada, food manufacturers have increased prices by just 1.3% in the past year, the slowest since 2019; these costs act as an excellent early indicator of future grocery prices, with a roughly six-month lead time. While we don’t look for an outright decline in food prices, groceries will be much less of a driver of inflation in 2024.

“Somewhere, over the rainbow”: Inflation also found a spark from the re-opening and revenge travel—as it turned out, it was the revenge of endless lines and higher costs. For countries that were shut down a bit longer, such as Canada, the pent-up demand was even more ferocious and led to even bigger initial spikes in travel costs. For example, at one point in the summer of 2022, when inflation was truly raging, Canadian airfares were up 58% y/y and hotel rates were up 50% y/y. The latter have eased somewhat to a (still-hot) 10% y/y clip, while airfares are reportedly down more than 20% y/y. (Enquiring minds would like to know: Which airline is StatCan flying on?) Yet even the U.S. also reports a 13% drop in airfares, following a 40% burst last fall.

“There’s no place like home”: Shelter costs were a bit of a late-comer to the inflation parade, at least in the U.S. case, but they weighed in heavily by early this year. However, even here there are encouraging signs amid cooler house prices. After peaking at just above 8% y/y this spring, U.S. shelter costs have dipped below 7% and short-term trends are milder. Home price trends suggest OER will moderate substantially in 2024. But rents look to be one area that could be stickier than most, leaving underlying inflation higher than normal and keeping the Fed on edge. This is even more so the case in Canada, where rapid rent inflation—now at a 40-year high of 7.3%—shows no sign of braking amid torrid population growth. While home prices have turned down again in recent months in Canada’s biggest cities, mortgage interest costs are up 30.6% y/y, and will only relent when rates start slipping—i.e., likely the second half of 2024.

“Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain”: Underlying much of the moderation in a broad swath of prices is the fact that demand has cooled considerably in almost all major economies. And, of course, that’s largely due to the sustained tightening in monetary policy across the industrialized world, save Japan. Led by the Fed’s 525 bps of rate hikes, yields have swept higher almost around the world. Even with the recent pullback, 10-year Treasury yields of nearly 4.5% are still up 300 bps from where they stood just two short years ago. Thirty-year mortgage rates have jumped even further, rising 430 bps over that period (to 7.61% in the latest week). At these levels, rates will further blunt spending and chill housing markets, ultimately further dampening core inflation.

Markets have now turned their attention, in laser-like fashion, to when the Fed and other central banks may start cutting rates. While we are now more optimistic that inflation can be quelled without severe damage, we continue to believe that the Fed and others will err on the tight side. Accordingly, even with the much better recent inflation news, we look for rate cuts to only begin in the second half of next year. For those looking for much earlier relief, we would never stoop to quoting Scarecrow one more time when he suggested that “some people without brains do an awful amount of talking, don’t they?”

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.