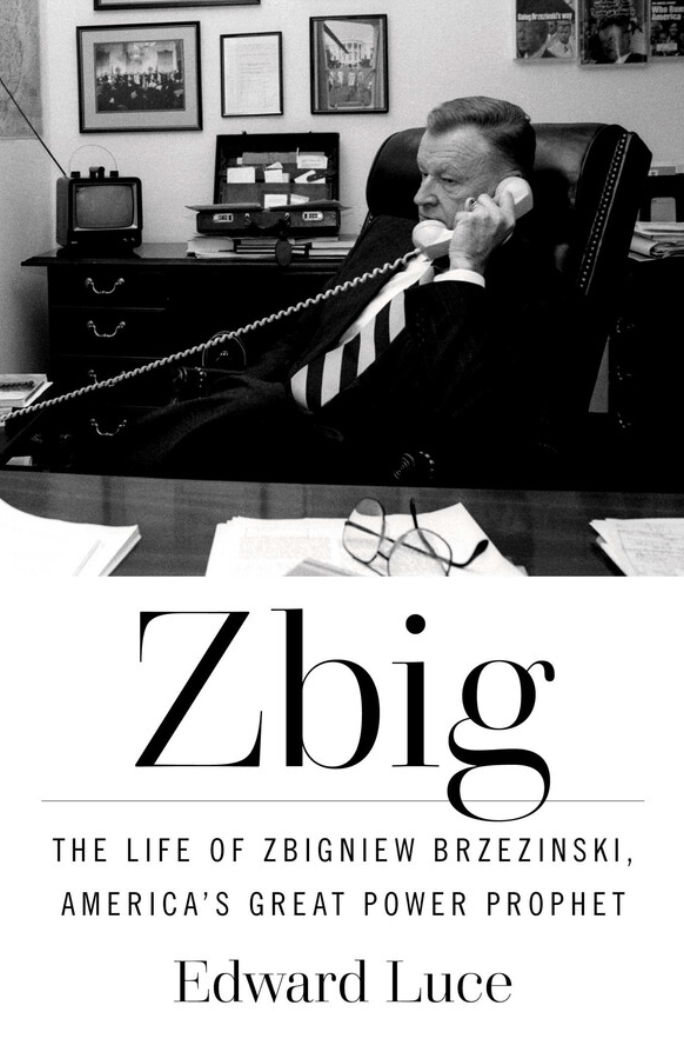

Ed Luce’s ‘Zbig’: Brzezinski Finally Gets His Due

Zbig: The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America’s Great Power Prophet

By Edward Luce

Simon & Schuster/2025

Reviewed by Colin Robertson

June 9, 2025

“I was aware” wrote the 17-year-old Zbigniew Brzezinski as the crowds in Montreal celebrated VE-Day on May 8, 1945, “that half of Europe was in the hands of another menacing dictatorship just as brutal as Hitlerism.”

This fierce sense of the hard realities of geopolitics and its implications for people and nations would guide Brzezinski for the rest of his long life.

Zbig: The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America’s Great Power Prophet by Edward Luce, the accomplished Financial Times US national editor and columnist, draws on Luce’s conversations with Brzezinski before he died in 2017 at age 89, on Brzezinski’s personal diaries, and on his vast output as a scholar and public intellectual. It also draws on interviews with those who knew the formidable former national security advisor, including his foreign policy and career rival, Henry Kissinger.

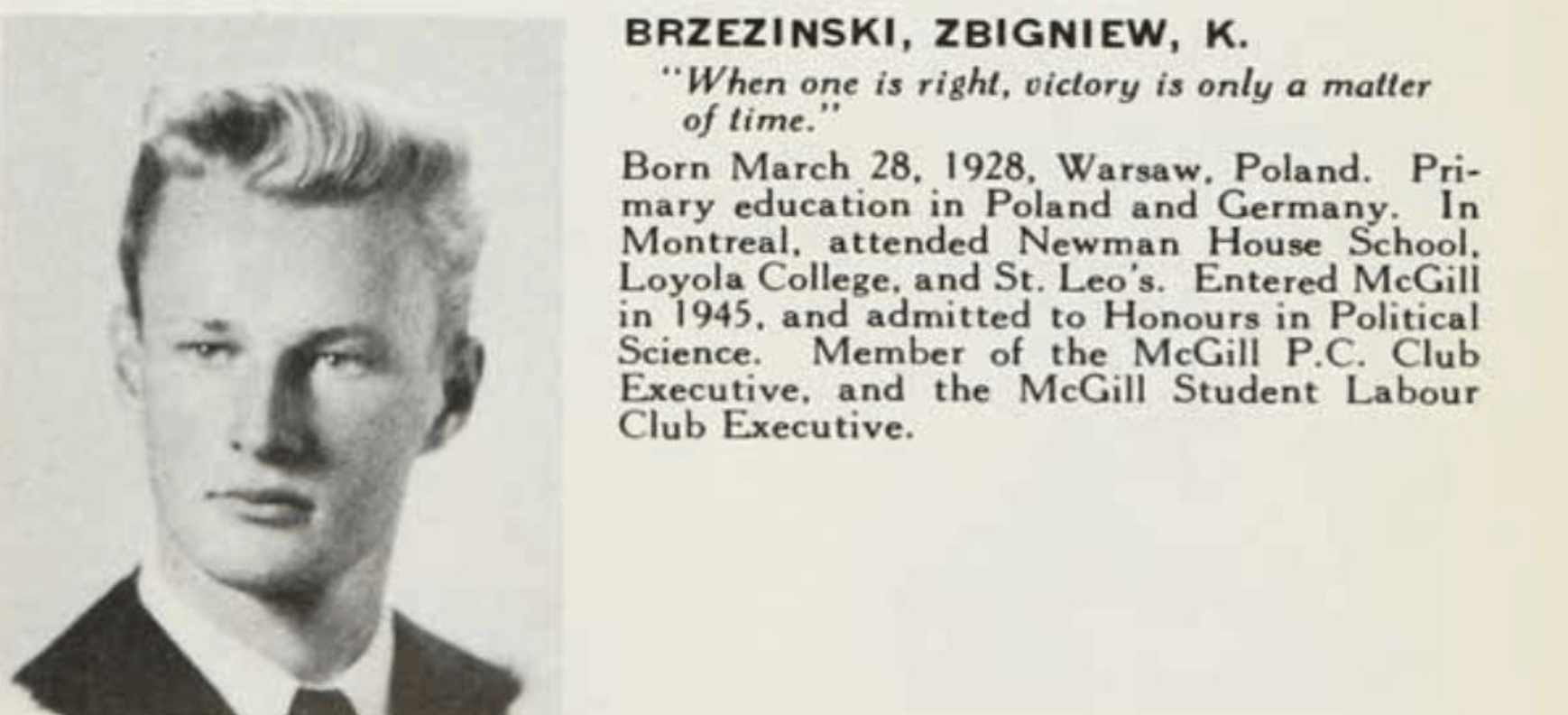

Brzezinski was born into the Polish gentry in March 1928, with his father, Tadeusz, serving as a diplomat in Germany during Zbigniew’s early childhood as the Nazis were rising to power. Zbig begins with his early years in the interwar life of what we used to call Mitteleuropa, followed by his family’s move to Montreal when he was ten. His father served as the Polish consul general in the city throughout the war years, with Brzezinski graduating from Loyola and McGill before moving to Harvard to do his PhD, then to teaching at Columbia University during the 60s.

He provided advice to Republican and Democratic politicians, including President John F. Kennedy and President Lyndon Johnson. Working with David Rockefeller, he was instrumental in setting up the Trilateral Commission.

Zbig befriended and tutored a longshot Democratic candidate for the 1976 presidential nomination; former naval officer, peanut farmer, and Georgia governor Jimmy Carter. Carter beat Gerald Ford and Brzezinski became his national security advisor.

Zbigniew Brzezinski, right, playing chess with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin at Camp David, September 1978/White House photo

Zbigniew Brzezinski, right, playing chess with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin at Camp David, September 1978/White House photo

Luce writes that Brzezinski soon eclipsed Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, as the administration jockeyed through the 12-day Israel-Egypt Camp David negotiations, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, diplomatic recognition of the People’s Republic of China, the fall of the Shah of Iran and the 444-day Iranian hostage crisis. After Carter’s loss to Ronald Reagan, Brzezinski returned to academe as a professor, first at Columbia University and then at Johns Hopkins SAIS, securing his reputation as a writer and as a public intellectual.

While he was multidimensional when it came to great power strategy, Brzezinski’s one big idea, writes Luce, was on how to manage the Soviets. It was an idea informed by Brzezinski’s conviction that the Soviet Union was far weaker, in far more fundamental ways, than western conventional wisdom had grasped.

From the 1949 McGill University yearbook

In his McGill MA thesis, Brzezinski identified the “nationalities problem” as the Soviet Union’s “Achilles’ heel.” Non-Russians, he argued, whether inside the Soviet Union or the Warsaw Pact satellites, retained and quietly cherished their sense of national identity. For them, dislike of Russian imperialism transcended the false appeal of Marxist internationalism. Harnessing this resentment, Brzezinski argued, would hasten the demise of the Soviet bloc.

Brzezinski took a hard line on the SALT II arms talks that Reagan would build upon. He also ramped up soft power through vehicles like Radio Free Europe, cultural exchanges and applying the human rights provisions of the 1975 Helsinki Accords. He also collaborated with his fellow Pole, Pope John Paul II, united in their shared support for future Polish president Lech Wałęsa’s pro-democracy Solidarity movement as it arose from the Gdansk shipyards. With the pontiff’s number on speed dial labelled “P”, Brzezinski and the pope successfully deterred a Soviet invasion of their shared homeland in 1979.

Motivated less by ideology than anti-ideology and imbued with a strong Catholic faith that informed his bedrock support for human rights, Brzezinski got the biggest foreign policy question of his generation right, an insight that eluded the patrician establishment, including two secretaries of state, Vance and Kissinger.

I met Brzezinski at what was then the Paul Nitze School at Johns Hopkins — now the Johns Hopkins School for Advanced International Studies — on Embassy Row (as separate from the main Johns Hopkins campus in Baltimore) while posted at our Washington embassy. The once-scorned Cold War hawk was now venerated as a dove because he opposed the US intervention in Iraq, telling Congress it would “likely lead to a head-on conflict with Iran and with much of the world of Islam at large.” Famously flinty, when I asked Brzezinski about his time in Canada, he mellowed. He spoke warmly of the farm his father bought after the end of WWII in Morin Heights, north of Montreal, and of skiing in wintertime.

Like Bach, who composed concertos to masses, Kissinger developed extraordinary intellectual range from the Congress of Vienna to artificial intelligence. Like Chopin’s Grande Polonaise, Brzezinski never wavered from his one big idea.

Brzezinski never pulled his punches. He had no time for counter-culture protesters during the 60s. Luce writes that Zbig considered them “spoiled brats from suburban homes risking nothing”, describing their protests as “the death rattle of the historical irrelevants.”

When I asked a Beltway pundit about Brzezinski and Kissinger — whose tenure as secretary of state was the foreign policy prize that eluded Brzezinski — he compared them to the Salieri and Mozart of the 1984 Milos Forman film Amadeus. While which one you consider the Amadeus of the equation likely depends on your political views, I think a better comparison would be Kissinger as Bach and Brzezinski as Chopin. Like Bach, who composed concertos to masses, Kissinger developed extraordinary intellectual range from the Congress of Vienna to artificial intelligence. Like Chopin’s Grande Polonaise, Brzezinski never wavered from his one big idea.

In that sense, Brzezinski and Kissinger were the near-perfect embodiments of Isaiah Berlin’s hedgehog and fox: Brzezinski the hedgehog who knew one big thing and viewed the world through the lens of that idea — that the Cold War would not be won by communism as long as the West remianed resolute — and Kissinger as the fox whose knowledge was vast, whose principles were more fungible, and whose worldview could not be condensed into one overarching, immovable idea.

The German-born Kissinger was the more celebrated, better at cultivating the media and more subtly ruthless. Both trained at Harvard, Kissinger the international historian and Brzezinski the Sovietologist.

Frenemies of long standing, they would regularly lunch together at the best restaurants in Washington. Both were profoundly influenced by what they witnessed before coming to North America. Kissinger, who would outlive Brzezinski, told Luce that, “As immigrants we knew about the fragility of societies and we had an instinct for the transitoriness of human perceptions,” adding, “The question is whether Americans can ever understand that they are living in a continuous experience that has no end and that you can never segment life into different problems… Europeans knew that we were living in a continuous history. It never comes to an end.” And for both, their formative years gave them an appreciation that despite best efforts, the possibility — indeed, the inevitability — of tragedy always lurked in the background.

Radek Sikorski, now Poland’s Foreign Minister, observes that if Kissinger brought a western European perspective to American strategic thinking, Brzezinski “infused it with the sensitivity of Europe’s captive East.”

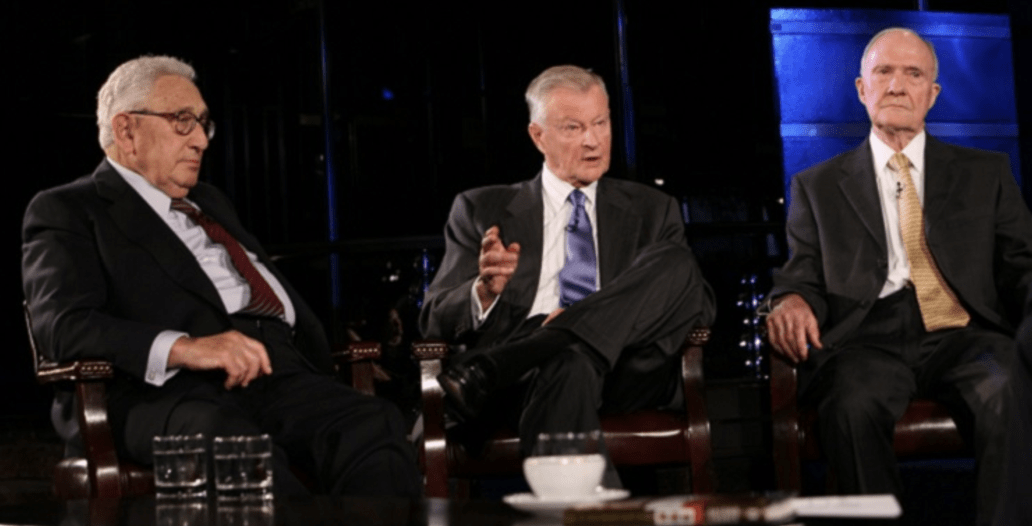

Henry Kissinger, Zbgniew Brzezinski, and Brent Scowcroft being interviewed by Charlie Rose at The Rainbow Room in 2007/Charlie Rose screencap

Brzezinski and Kissinger were both grand strategists of a mindset that the world, especially middle powers like Canada, need now more than ever. To get a sense of their breadth of vision, their uncanny prescience and their rivalry, watch Charlie Rose’s 2007 interview with Brzezinski, Kissinger and Brent Scowcroft at a Center for Strategic International Studies event (above).

Ever the contrarian, early in the post-Cold War period characterized by great triumphalism in America, Brzezinski warned in his book, Out of Control: Global Turmoil on the Eve of the 21st Century (1993) that hubris would lead to problems for a unipolar United States. Americans saw themselves at the top of the ladder. It was Fukuyama’s “end of history” but only a matter of time before others climbed up the ladder to challenge US supremacy. Brzezinski coined the phrase ‘Alliance of the Aggrieved’ to describe China, Russia, Iran and North Korea, countries that felt they were on the losing side of history.

Brzezinski died four months after Donald Trump became the 45th president. He had summed up his fears in his final tweet: “Sophisticated US leadership is the sine qua non of a stable world order. However, we lack the former while the latter is getting worse.” His ability to read geopolitics was exceptional to the end.

Luce’s story of Brzezinski and his times is narrative history at its best. It describes the kind of thinking that we need very much today especially as the West confronts a more muscular “Alliance of the Aggrieved”.

Required reading for all diplomats, Zbig is essential to anyone interested in strategy and its intersection with politics and public policy, and as a testament to the truth that men are not always shaped by the forces of history. Sometimes, it’s the other way around.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.