Fighting the Fed… and the BoC

December 2, 2022

Douglas Porter

Inflation fears dominated the market narrative for the first ten months of the year, powering global yields dramatically higher, flinging the U.S. dollar forward, and pounding equity valuations. Yet, as we rapidly approach the end of 2022, the market is engaged in an aggressive counter-trend move almost across the board. Commodities turned first, with broad price measures peaking all the way back in early June, and oil prices now bouncing around their lowest level of the year. Then each of the dollar, yields, and stocks turned the corner in October. While today’s moderate high-side surprise in the PPI has at least temporarily stalled the move, the bigger picture is that since the autumn extremes:

- The trade-weighted U.S. dollar is down 7%

- Ten-year Treasury yields are down more than 70 bps (and 5-year GoCs have plunged more than 80 bps)

- U.S. retail gasoline prices are down 34% (since June), and

- Broad stock indices are up 11%.

The late-year reversal reinforces the point that financial markets have handled a suite of challenging events with remarkable resilience. The re-pricing to a significantly higher interest rate reality has been painful for most portfolios, yet still quite orderly, with no obvious stress fractures. But this generally resilient market performance ironically makes the Fed’s job that much more challenging. A step down to a 50 bp rate hike is all but locked in for next week’s FOMC meeting (after a string of four consecutive 75 bp hikes), and we look for two more 25 bp moves in the first two meetings of 2023. The risk to this call is that the Fed may need to do even more, to more forcefully soften overall financial conditions and ensure that underlying inflation is squashed.

Our broad macro view can be summarized as a little more downbeat than the consensus on growth, but more concerned about the persistence of core inflation in 2023. For example, the latest consensus (survey conducted just this week) expects U.S. GDP growth of 0.2% next year, while we are at 0.0%; and average CPI inflation of 4.1%, while we are at 4.8%. It’s a broadly similar picture for the core PCE deflator, where the consensus looks for a cooldown to 3.7% next year, while we are at 4.2%. Sidebar: The consensus call on growth and inflation have been largely unchanged in the past three months, after a stream of downward revisions to growth and upward revisions to inflation in the prior six months.

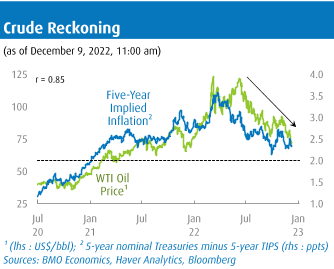

One important development that could swing our forecast more in line with the average call is the ongoing slide in oil prices. It is quite telling that crude slid roughly 10% this week to around US$71 in the wake of a wave of cross currents. In short order, oil had to digest the OPEC+ meeting (production was held steady), the EU’s $60 price cap on Russian oil, China’s baby reopening steps, and a Keystone pipeline spill. Likely overriding those fundamental factors has been the macro backdrop, with markets pricing in a deeper global slowdown in 2023. With oil and U.S. gasoline prices now probing their lowest level of the year, this clearly takes the edge off headline inflation and inflation expectations, and will also provide some immediate relief for consumers. The University of Michigan’s latest survey found that consumer short-term expectations of inflation are easing somewhat (one-year at 4.6%), although the five-year view is holding steady at 3.0%.

Just ahead of the FOMC meeting, the U.S. November CPI report will provide an ample appetizer on Tuesday. Expectations for the figure are toggling around a non-descript headline rise of 0.3%, which would clip the annual inflation rate to roughly 7.3%; the risk is for a slightly meatier core result of 0.4%, which would only shave the annual pace a tick to 6.2%. Given a mild high-side surprise on the PPI, markets would likely readily digest this outcome, and move on to the Fed the next day. However, the past two years have certainly taught us to never take the CPI for granted. With high-side surprises the norm since early 2021, it would be an important development if the U.S. managed a second consecutive low-end result. Suffice it to say, we doubt that will be the case, especially for core.

Canada’s calendar is lighter next week after the showpiece Bank of Canada decision this past Wednesday. The semi-aggressive 50 bp hike reasserted the Bank’s position as the world’s top hiker in 2022 (at least until the Fed weighs in next week), with a cumulative 400 bps of rate increases and a top overnight rate of 4.25% (tied with the RBNZ). But market reaction was muted to the minor surprise on the rate hike size due to a mild message—after months of flatly stating that rates needed to rise further, the Bank said they would now debate whether that was still the case. We continue to expect that the answer will be “yes” one more time, with a 25 bp hike anticipated for January, to a terminal rate of 4.50%.

Arguably, the Bank has an even bigger challenge on its hands with recent financial market moves. While equities slipped this week, the TSX is still down by little more than 5% YTD. Even with some recovery in recent weeks, the Canadian dollar is still down 7% y/y, keeping pressure on import costs. But, most importantly, the bond market is absolutely fighting the BoC, with long-term issues rallying furiously in the past two months. While there is intense focus on the deep yield curve inversion in Treasuries, the GoC market is even more extreme. To pick but one example, the overnight rate is now a towering 140 bps above the 10-year yield. That gap is at a 30-year extreme and has almost never been wider than 50 bps in that period.

Essentially, the market is assuming that the Bank will be slashing rates by the second half of next year as—presumably—inflation melts away. This is where we distinctly deviate from the consensus and the markets. Similar to the U.S. outlook, our call on Canada for 2023 can be characterized as a wee bit lower on real GDP (consensus is now 0.4%, we are 0.0%) and higher on inflation (consensus is for average CPI of 3.8%, we are 4.6%). Our call would leave no leeway for rate reductions in 2023.

The reason why this divergence in views is so important is that if the Bank is indeed cutting rates by the second half of 2023, this could help resuscitate the housing market in relatively short order. Next week’s national housing data for November are expected to show a near-40% y/y drop in existing sales and a 4% y/y decline in prices on the MLS HPI metric. But, if anything, the market’s fundamentals may show stabilization amid a pullback in listings. Both potential sellers and heavily indebted owners are likely holding on, waiting for rates to ultimately recede. And the steep drop in the key five-year GoC yield from the late-October peak of 3.86% to 3.05% now will simply feed that narrative. In a word, that pullback in yields just means that the Bank will need to keep short-term rates higher for longer as a counterweight. You can fight the BoC, or the Fed, but you can’t win.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.