Getting Really Real

Douglas Porter

August 18, 2023

Where are the serious economic and/or financial cracks going to first emerge? Some version of that has been the most common question we have fielded since the Fed and other central banks embarked on the intense tightening campaign of the past 18 months. Could the answer be China? It certainly felt that way this week, as deepening property woes and another raft of disappointing economic data from the world’s second biggest economy sent shudders through global financial markets. It was nearly a full-on risk-off week, as the S&P 500 fell more than 2% (now down almost 5% for August), the U.S. dollar neared its high for the year, oil fell to around $80, and even bitcoin took a big step back in a tough week for financial markets.

One major market did not follow the risk-off script—government bonds. Instead of rallying in the face of stress, as they so often do, bonds joined in the selling parade, taking a variety of yields to multi-year highs. In fact, it may well be that the relentless back-up in long-term yields itself is the root cause of the market’s recent angst, moreso than China concerns. The benchmark 10-year Treasury yield pierced the 4.3% threshold this week, and saw its highest close—at that level—since November 2007. As recently as April, it was probing 3.3% in the wake of the regional banking squall. This abrupt rate rise has spilled over into mortgages, where the 30-year rate broke above 7% in the latest week, threatening to add a new down-leg to housing.

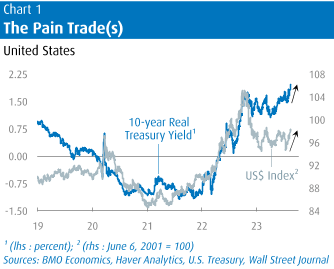

Perhaps of most concern for markets is what’s driving the steady rise in long-term yields. It’s not higher inflation expectations, as the 10-year breakeven rate has been locked in a relatively narrow range around 2.3% for a year now. Instead, the sell-off has been keyed by real interest rates, which are forging higher across the board. The real 10-year Treasury yield is now on the cusp of hitting 2% for the first time since 2009, while all other major maturities have long since broken through that threshold. To put today’s levels in perspective, the 10-year real yield was basically at zero just before the pandemic, and promptly dropped deeply negative for the next two years—at least until the Fed started tightening and engaging in QT.

Why are real yields on the march? The ball really got rolling in early 2022, when central banks and markets collectively realized how far policy had fallen behind the inflation curve, and tightening commenced. Instead of buying bonds, central banks are now busily reducing their massive holdings. Piling on has been Fitch’s downgrade (on Aug. 1) and a tidal wave of supply, juiced by a doubling of the U.S. budget deficit to more than $2 trillion in the short space of a year. Geopolitics may be playing a small role, as Russia has essentially cut its holdings of Treasuries to nil and China is seemingly headed in that direction, steadily reducing its holdings by $265 billion since the first quarter of 2021 to $835 billion now (a 24% slice). Even Japan, again the largest holder of Treasuries, has trimmed its exposure by 10% in the past year to $1.1 trillion, as domestic JGBs now offer a semi-respectable 0.63% 10-year yield.

The rise in real yields back to levels that were pretty much the norm prior to the Global Financial Crisis may be a clear signal that the long-term rate outlook has truly shifted. A return to solid positive real yields has a variety of important implications, and some are less than pleasant:

- Gone are the easy days for public finances. Negative real rates were a godsend for governments, especially during the pandemic, allowing them to borrow heavily without sustaining serious damage to long-term finances. Positive real rates will ultimately impose much more discipline, a reality that perhaps not all policymakers have cottoned onto yet.

- Household borrowers also had access to historically cheap credit for more than a decade, and saw persistent windfalls through renewals into lower mortgage rates. The latter will instead be a meaningful headwind for what looks like years to come.

- Asset valuations will ultimately need to readjust to a different world for real interest rates—real estate (yes, including housing), equities (which arguably have already partially adjusted through last year’s bear market), and more speculative assets.

- On the positive side of the ledger, the return to robust real rates is a boon for pension plans, as the long-term liabilities are much more heavily discounted. It’s also good news for savers, who have been punished mercilessly for more than a decade of extremely low and even negative after-inflation rates.

Of course, if the economic outlook was particularly weak, real yields would likely not be making the upward move of the past few months. But adding to the advance has been a drumbeat of upward revisions to the near-term U.S. outlook by a wide variety of analysts—present company included. Perhaps most eye-popping is the early read on Q3 GDP growth by the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow of a towering 5.8%, which, you know, is a pretty long way from recession. The result popped higher on upside surprises in retail sales and industrial production, the latter of which revealed U.S. auto production was at its highest since pre-pandemic days.

Amid the steep rise in yields, all eyes and ears will turn to next Friday’s sermon from the Teton Mountains by Jay Powell (10 am, from Jackson Hole). Recall that last year’s effort was a terse “there will be pain” lecture, presaging the 300 bps of additional tightening in the past year. Expectations are running high that the Chair may revisit the issue of the neutral or natural rate of interest (aka r-star), a topic he delved deeply into in 2018’s speech, when real rates were still mired well below 1%. This is ultimately a much more important issue than whether the Fed will hike one more time this cycle—we and the market lean “no”—or when rate trims may commence. The bevy of solid data and the latest rise in yields suggest that day may be even further away than our call of late next spring.

Canada was certainly not left out of the selling pressure in bonds or stocks. In fact, the TSX had its worst day of the year on Tuesday, was down 3% on the week, and is now just hanging onto a slender gain for all of 2023. A high-side CPI result for July added to the sour mix—the 3.3% reading leaves Canada’s inflation rate above that of the U.S. for the first time since pre-pandemic days in 2019. This put some additional pressure on domestic yields and nudged up the chances that the Bank of Canada goes back to the tightening well one more time. While market pricing doesn’t yet see a move in September, it has almost fully baked in one more by year-end.

In turn, the key five-year bond yield has vaulted well above the 4% threshold for the first time since late 2007. Barely three months ago, that important yield was still below 3%, a nasty turn of events for the housing market. Our view is that these higher yields will thus do some of the dirty work for the Bank, and, along with a weakening job market, suggest that further rate hikes won’t be necessary. However, keeping rates steady will mean the Bank will have to grit through what’s likely to be another nasty rise in headline inflation next month to above 3½%.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.