Grief as Defiance: How Muscovites Mourned Navalny

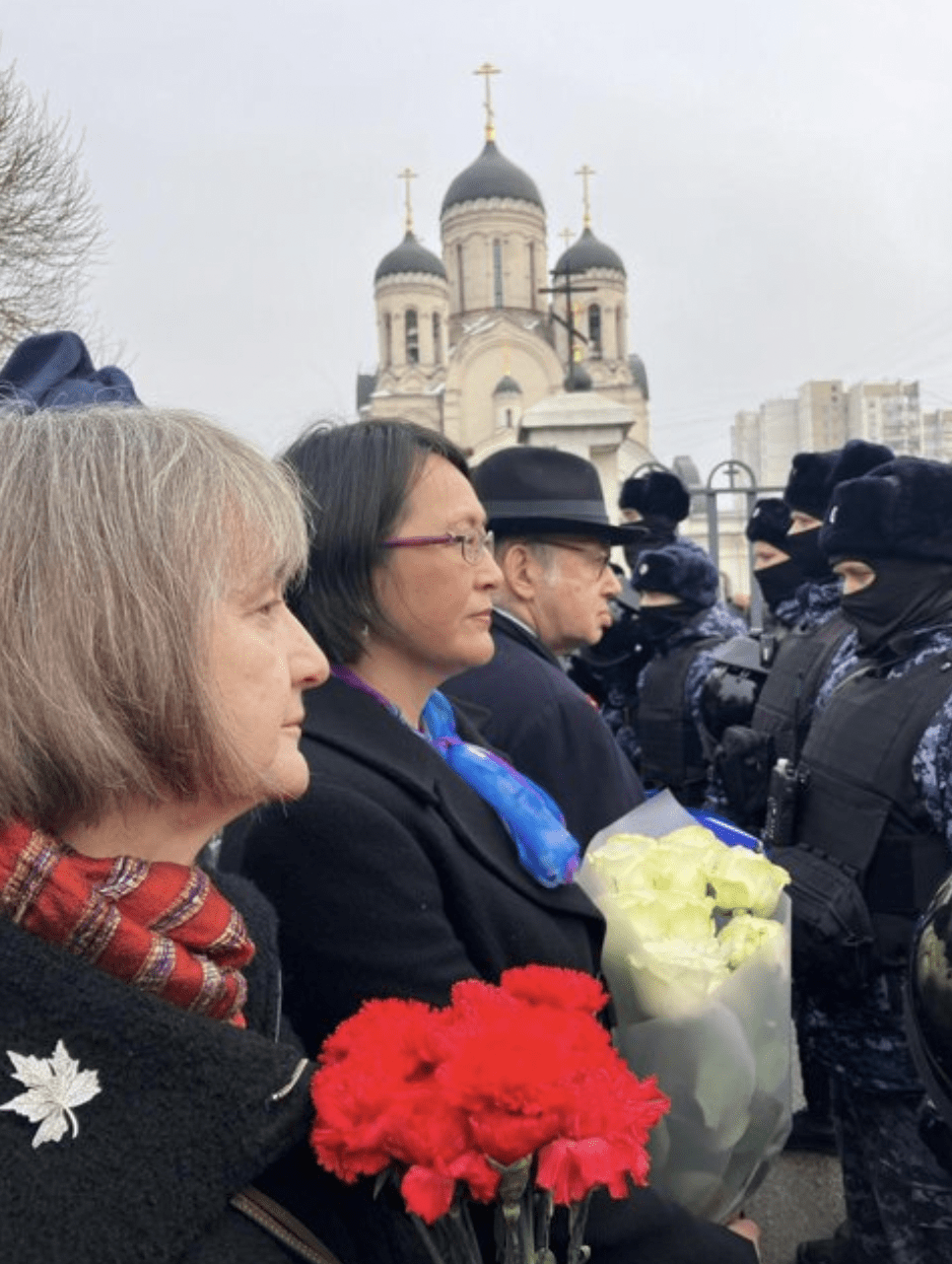

Paying respects: Ambassador Sarah Taylor attends Alexei Navalny’s funeral/Sarah Taylor X

Paying respects: Ambassador Sarah Taylor attends Alexei Navalny’s funeral/Sarah Taylor X

By Sarah Taylor

March 15, 2024

On the first Friday in March, two weeks after the death of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny in an Arctic penal colony, I stood outside the Quench My Sorrows church in the Maryino district of suburban Moscow where his funeral was being held.

Facing me and fellow ambassadors was a line of riot police in full gear. Behind us, across the church entranceway, stood another line of riot police. Behind them were thousands of Russian citizens who had come to say goodbye.

Although only about 60 people were allowed into the church, by one estimate over 16,000 people waited outside the church and at Borisovskoye Cemetery to pay their respects to Navalny. They called out his name and threw flowers at the hearse as it drove by. They walked for 30 minutes from the church to the cemetery and waited hours in the cold, kettled by police and crash barriers through the narrow gate to leave flowers at the graveside.

Prison authorities initially refused to release Navalny’s body to his mother. She bravely persisted, making the funeral in Moscow possible. Standing in the crowd outside the cemetery, I understood what the authorities were afraid of. In addition to Navalny’s name, cries of “No to war!” and “Ukrainians are good people!” were heard from the crowd. The Kremlin’s narrative of unified support for the “special military operation”, and of near-universal support for Putin’s re-election as president on 17 March, was contradicted.

This is despite the Kremlin’s efforts to make life in Moscow, as much as possible, like life in a bubble. The New Year’s lights still twinkle brightly on the streets and bridges, the cafés and restaurants are full, and you can still shop for Max Mara and Prada in luxury department stores. Only the patriotic signs urging readers to join the military, support heroes and love Russia remind you of the war – and, of course, if you turn on the television, the extreme nationalist rhetoric on the talk shows.

In addition to Navalny’s name, cries of ‘No to war!’ and ‘Ukrainians are good people!’ were heard from the crowd.

Mainly, though, the government has been trying hard to convince Muscovites, after their initial shock in February 2022, that life continues as usual despite the “special military operation”.

Announced in a court press release by the prison service on February 16, Navalny’s death was given only a brief mention on the television news – but word spread fast, nonetheless. Despite his flaws of ego and nationalism, Navalny was the face of opposition to Putin’s Russia.

Standing with France and New Zealand/Sarah Taylor X

Instinctively, people knew where to go and how to respond. When I went the next day to lay flowers in memory of Navalny at the Solovetsky Stone, a memorial outside the former KGB headquarters to the victims of the gulags, a small but steady flow of people were already lined up to do the same. Although not arresting anyone at that point, as happened later and elsewhere, police were checking IDs and taking photos, but they did not stop the mourners. Over the course of Saturday afternoon, the pile of flowers grew to close to a metre in height.

Some commentators suggested initially that only a small and dwindling number of urban intellectuals cared about Navalny. The turnout before, during and after his funeral — mourners were still laying flowers at the cemetery nine days later — says otherwise. In addition, close to 150,000 signed the nomination papers for a would-be presidential candidate who opposed the war; signing was an act of bravery in and of itself.

Moscow today is essentially late Soviet-era Moscow, but with better public transport, restaurants, and shopping.

The public response to Navalny’s death shows that Russians’ support for the war is not as unanimous as the Kremlin would have us (and its own people) believe. We must be wary of portrayals of Russia as a political monolith. Of course, there are many in Russia who support and participate in the war; hardly surprising when they are bombarded with official propaganda and cut off from most other sources of information.

If they manage to see through this fog of disinformation and are courageous enough, and outraged enough, to protest, they face harsh repression. To give just a few examples, veteran human rights activist Oleg Orlov — longtime head of the banned Nobel Prize-winning NGO Memorial — was just given a sentence of 2.5 years for saying that Russia has become a fascist state. Academics must report and explain their contacts with foreign diplomats. Middle-of-the-road media outlets have moved abroad because of the restrictions on them if they stay. Single protesters holding signs quoting the Russian constitution are arrested. By some estimates, the number of political prisoners in Russia now equals those of the USSR under Khrushchev and Brezhnev. Moscow today is essentially late Soviet-era Moscow, but with better public transport, restaurants, and shopping.

In the privileged centres of Moscow and St. Petersburg, the impact of the war is mainly felt in inconveniences at this stage. The longer-term prospects, however, look much gloomier. War casualties and the flight of young Russians abroad are only worsening aging demographics. Military spending is going towards equipment that is being left to rust on the battlefields of Ukraine, and has fueled inflation. Structural problems in the Russian economy, notably the corruption against which Navalny’s movement fought, remain unaddressed. Chinese imports are now propping up that economy. While the lights are bright in Moscow now, the future is much less so.

It is not easy being the representative of an “unfriendly country”, as we are deemed by the Russian government, these days. We have little access to government officials, and when we speak, those conversations tend to be difficult. But I am inspired by the small number of brave Russians I have met who are continuing to speak their mind, to observe elections, to help migrants and to memorialize victims of past and current repression.

Canada’s support for Ukraine, and our condemnation of Putin’s brutal invasion, remain steadfast. On an otherwise tragic day in Moscow, I was heartened to see that there are many Russians who also want to see an end to the war, and a better future.

Sarah Taylor is Canada’s Ambassador to Russia.