Higher for Even Longer

Douglas Porter

June 30, 2023

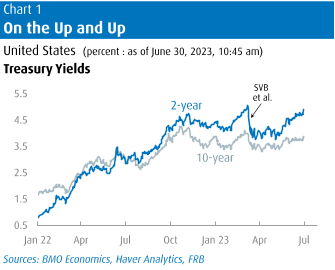

The key theme in markets as we approach this year’s half-way point is the renewed upward march in long-term interest rates. Having brushed aside the regional banking squall, and dispensed with the debt ceiling drama, investors are left with the realization that the underlying economy is much firmer than expected at the start of 2023. And, while headline inflation is dutifully coming down the mountain in most major economies—courtesy of $70 oil—core inflation is barely budging, as job markets remain taught and housing stabilizes. For markets, the combination of a resilient economy and sticky underlying inflation is a mixed blessing for equities, but a tough pill to swallow for bonds.

Treasury yields are again approaching the peaks hit in early March, just before they were so rudely interrupted by the collapse of SVB. Even with a small pullback on Friday, the 2-year yield is within reach of the 5% handle, and is now up more than 100 bps from the lows of just two months ago. In a similar vein, the 10-year yield is spying the 4% threshold and, at just over 3.8%, is up more than 50 bps from the spring nadir. Some tough talk by Chair Powell at this week’s confab in Portugal strengthened the view that Fed rate hikes will recommence next month after the briefest hiatus, reinforced by generally sturdy U.S. data this week. We are on board, but—like the market—we are not fully sold on a follow-up hike later this year. For now, we are sticking to the call that rates will stay at 5.25%-to-5.50% beyond July.

Arguably the centerpiece U.S. economic report this week was one that was barely mentioned ahead of time. After all, it’s not every day that a second revision to a quarterly GDP release will move any needles, but the large upgrade to Q1 was an eye-opener. Growth was bumped up 7 ticks to 2.0%, with notable strength in final sales. (We’re far too polite to mention that our initial forecast for the quarter way back in April was 2.0%, and that the statisticians have finally caught up with reality.) It’s true that real domestic income was much softer, actually dipping in the quarter. And, real consumer spending looks to be losing a bit of mojo, rising a modest 0.7% annualized in the three months to May. But the big picture is that the economy is grinding out modest growth, and is still a long way from recession.

Arguably the centerpiece U.S. economic report this week was one that was barely mentioned ahead of time. After all, it’s not every day that a second revision to a quarterly GDP release will move any needles, but the large upgrade to Q1 was an eye-opener. Growth was bumped up 7 ticks to 2.0%, with notable strength in final sales. (We’re far too polite to mention that our initial forecast for the quarter way back in April was 2.0%, and that the statisticians have finally caught up with reality.) It’s true that real domestic income was much softer, actually dipping in the quarter. And, real consumer spending looks to be losing a bit of mojo, rising a modest 0.7% annualized in the three months to May. But the big picture is that the economy is grinding out modest growth, and is still a long way from recession.

In fact, we nudged up our estimate of Q2 GDP to 1.5% (1.0% prior) in the wake of a string of sturdy U.S. economic releases, lifting the full-year estimate two ticks to 1.5%. For perspective, we had penciled in zero GDP growth at the start of the year, so it has been a steady and straight upward climb in the past six months. Still, we continue to pencil in small setbacks in GDP in the second half of the year, although our conviction on that call is admittedly low. We certainly would be reluctant to call it the R word… think more a “recessionette”.

The latest Blue Chip consensus survey, conducted just this week, finds that 54% of respondents believe that the U.S. economy will enter a recession in the next 12 months—almost a perfect 50/50 proposition. (Yet, an astonishing 100% believe the unemployment rate will be higher a year from now.) The bond market is clearly also having serious doubts about an outright downturn in the economy; note that the renewed back-up in yields has been almost entirely driven by rising real yields. Our fixed income strategists note that five-year real yields hit 2.0% this week, the first time at that threshold since 2008. Again, that upswing in real yields can be viewed as a quiet vote of confidence in the underlying strength of the economy.

Canadian yields have, if anything, seen an even bigger gallop higher from the spring lows. Even with a moderation this week, the two-year yield has been flirting with its highest level since 2001 at nearly 4.75% (and almost matching the overnight target). Canada is dealing with some very different dynamics than the U.S. economy, but the end result for the rate outlook is quite similar. Inflation has been consistently calmer in Canada, and it took a mighty step down in May to 3.4%, as expected. Core is also generally cooler, with the BoC’s main measures both a bit below 4%, while the Fed’s preferred PCE metric is now at 4.6%. Plus, the Bank’s latest Business Outlook Survey found easing of capacity pressures and signs that wage growth will moderate, which point to continued softening of inflation pressure in the months ahead.

Yet, despite that somewhat milder pricing backdrop, inflation expectations among consumers and businesses remain far too high for the Bank’s comfort. And, like the U.S., underlying growth is showing some steel. While April GDP was flat, the early read on May is for a rollicking 0.4% rise. Assuming the flash read on May is correct, this means that the Canadian economy has yet to see a single month of GDP decline this year, even as the consensus call at the start of 2023 was for a mild recession. Meantime, Canada’s population growth continues to power ahead, rising 0.7% in Q1 and up a towering 3.1% y/y, or the strongest year-on-year rise since the 1950s. It’s certainly fair to question whether such rapid population growth is optimal or sustainable, but there’s no question it adds to spending and flatters job tallies.

The bottom line is that we are also revising our Canadian GDP estimates higher for both Q2—to 1.5% from 0.8%—and for the year as a whole, also to 1.5% (from 1.3%). For reference, the BoC’s April calls are slightly below on both counts, as the Bank expected 1.0% growth in Q2 and 1.4% for the full year. That’s not enough to move the dial on the next rate decision, and the market sees it as a close call on the July 12 meeting. Early readings next week on home and auto sales for June will help inform the Bank on how the consumer is holding up. We have penciled in a final 25 bp hike, but it will likely come down to next week’s June employment report. Even if the Bank chooses not to hike further in July, the larger picture is that the risk remains for higher rates, for longer, and rate cuts are a 2024 story. For a final thought on that theme, we have long been of the view that central banks would begin trimming rates in early 2024 amid calmer inflation—we’re not changing that call, yet, but the risks are clearly tilting to a later start for rate cuts amid the resilient economic backdrop.

Having recently returned from the U.K., I can attest to the fact that if you think inflation and rising interest rates are a big deal on this side of the pond, it’s a different world over there. With the highest inflation in the G7 at 8.7% and core that just won’t quit at 7.1%, the U.K. has a very serious problem on its hands. While short-term bond yields are at their highest levels since 2008, that may not be high enough, given that two-year yields are still nearly 2 ppts below core inflation. While the debate in North America is whether rates need to go up another 25 bps or so, the question for the BoE is whether they need to go up another percentage point or so to quell inflation. The inflation/rate shock has taken on a much more political flavour than in Canada, and that’s with U.K. elections due next year. For now, the pound is taking the run of bad economic news in stride, supported by the prospect of even higher U.K. interest rates. But the U.K. economy looks closest to something akin to stagflation among the major economies, and that is in no way positive for the currency’s medium-term outlook.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.