Hollywood’s Cry for Help in a Glutted Melodrama Market

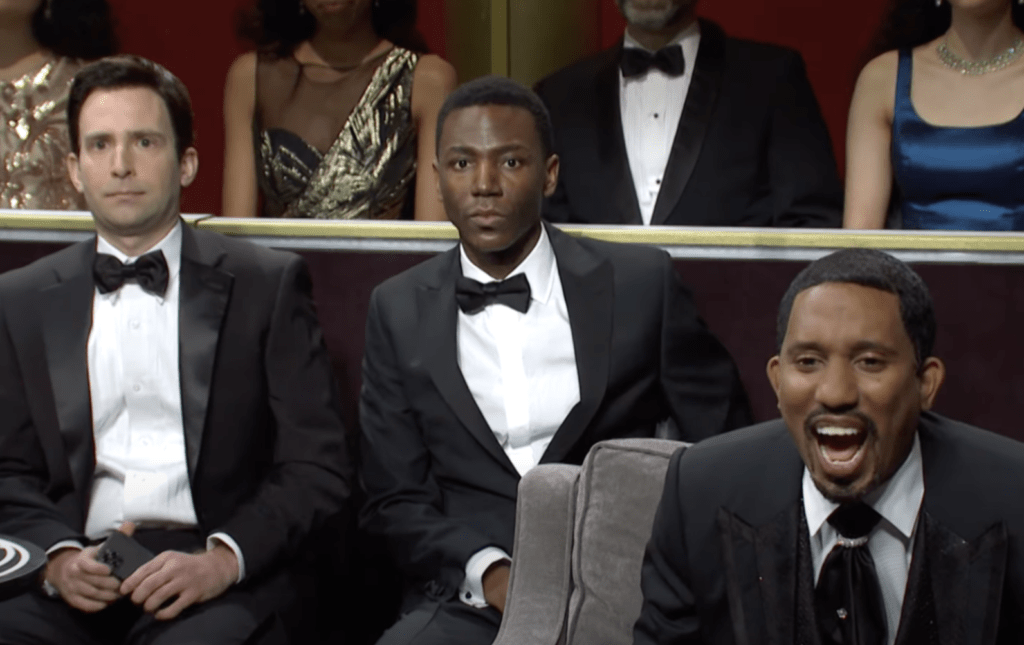

SNL’s take on Will Smith’s night at the Oscars/SNL

SNL’s take on Will Smith’s night at the Oscars/SNL

Lisa Van Dusen

April 2, 2022

Perhaps the most telling social anthropology angle of the moment when Will Smith slapped Chris Rock on the stage of the Dolby Theater in Los Angeles during the Oscars was that so many audience members in the room and around the world weren’t sure whether it was real.

Not that we weren’t sure that Will Smith’s hand had connected with Chris Rock’s face — that was obvious to the naked eye and captured for exhaustive replay, slo-mo and GIF posterity ad infinitum. It just took a few seconds for a species whose suspension of disbelief has been so fatefully recalibrated by propaganda, performative politics and “post-truth” untruthiness to discern whether the creative-on-creative, multimillionaire-on-multimillionaire assault they were witnessing in the middle of a traditionally assault-free Hollywood prom night was a misdemeanour under California Penal Code section 242 or just a bit.

What Will Smith did has been analyzed by comedians for its vocational infractions, by the police for its potential legal infractions, by Kareem Abdul Jabbar for its racial implications and by scores of contemplative observers on Twitter for its Rorschachian logrolling value. What most rational observers agree on is that walking onto the stage in the middle of the Oscars and slapping a presenter is not about the joke and it’s not about any backstory. In this as in so many human interactions and transactions, context is everything. If Will Smith had kept smiling and used his words on Twitter, Chris Rock would have been the one issuing an apology to Jada Pinkett Smith and alopecia sufferers everywhere the next day, along with a generous donation to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation.

As it was, the impact of Smith’s more kinetic choice on viewers across the world, on the Oscar winners and their families who, in many cases, had the biggest night of their lives hijacked by an act of utterly incongruous lunacy, and on the people in the room whose state of discombobulated shock was apparent in the standing ovation they volunteered for the scene within the hour was all duly noted by Smith in an apology issued after his adrenaline rush dissipated and the fallout began to register.

Among the truly interesting analyses of The Twenty Seconds That Ate the Oscars have been the takes invoking, of all people, Shakespeare. These include the theory that it was Chris Rock’s reckless disregard for the “curse of the Scottish play” when he said “Macbeth” out loud moments before he was smacked upside the head by a berserk best actor nominee, recalling that time when John Gielgud shanked Larry Olivier in a knife fight at the Baftas following a similar transgression.

New York Times legend Maureen Dowd has her own Shakespearean twist; that Smith succumbed to the hamartia, or tragic flaw, of his own self-destructive need for revenge in the moment. A classicist might refine that to the greatest hamartia of them all, hubris, in the form of excessive pride or inflated self-confidence that leads a tragic hero to deviate from reason and break moral law. Who the #&*$ knows?! One day, we may discover that a whole other set of subtextual variables, inducements and motivations were at play and that Judi Dench was just lucky she didn’t get coldcocked.

For now, perhaps we can blame it on existential angst. After years of economic embolization from streaming, cultural disempowerment from fragmentation, relentless upstaging from truth-is-stranger-than-fiction headlines, censorship pressure from totalitarian markets and unfair supply competition in the realm of melodrama from a steady parade of drama-queen amateurs including bachelorettes on the make, screwball politicians on the take, histrionic Supreme Court nominees and 12-year-old Tik Tok impresarios, Will Smith finally cracked for all of Hollywood and did the most preposterous, previously unthinkable thing he could think of. Hypercompetitive disorder as the new hubris.

On the upside, Chris Rock did the best thing he could have possibly done — personally and professionally — to salvage a moment that was showstopping for all the wrong reasons and for which there was no precedent and no script. Live. In front of 16.6 million people.

He shook it off and did his job.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine. She was Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.