‘Hope is a Woman’s Name’: Leading Between the Lines

Hachette/March 2022

Review by Gray MacDonald

October 24, 2022

Being a teacher is never easy. Being a teacher at a grade school in an unrecognized Palestinian village in Israel during the roller-coaster years of the Oslo process is a whole other level of stress. So, after losing her position – in part for having told her students how to stand up for their rights – Amal Elsana-Alh’jooj expected the call from her former boss to be about her being a troublemaker.

She wasn’t quite expecting him to offer to write her a letter of recommendation for university. But as the late civil rights icon John Lewis never tired of reminding us, there’s a difference between bad trouble and good trouble. The letter helped her secure a social work fellowship in Canada.

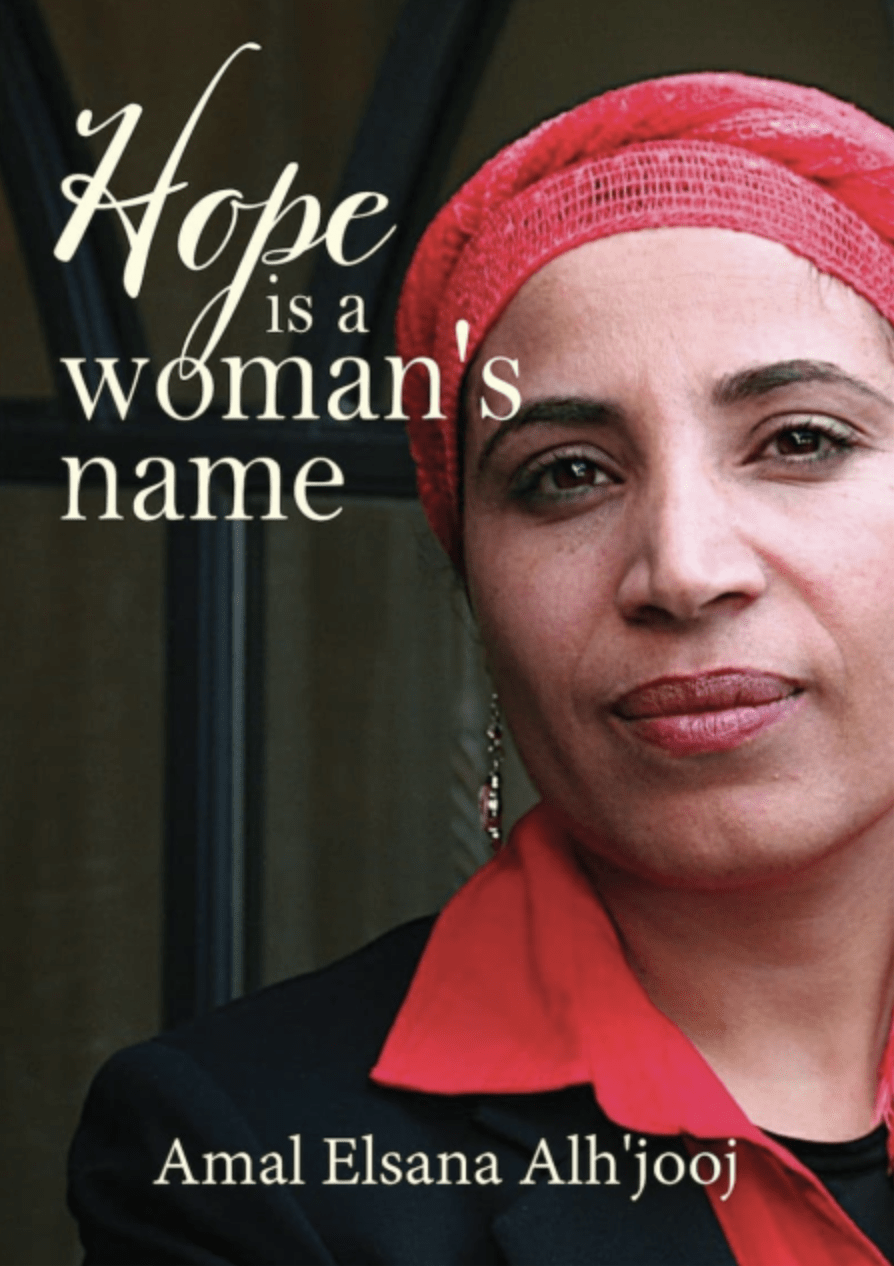

Elsana-Alh’jooj — the first name Amal means “hope” in Arabic, hence the book’s title — has a talent for using examples from her own life to illustrate a point, and she seems to have infinite fodder for these. Elsana-Alh’jooj has managed to pack several lifetimes worth of challenges, emotions, and social impact into one book, Hope is a Woman’s Name.

The memoir is made up of vignettes; anecdotes strung together in roughly chronological order to paint a picture of an entire life. As human beings, we’re made up of all the instances that have left the greatest impression on our psyches, and Elsana-Alh’jooj has mapped out those moments for the reader as a guest along a journey. As with the archetypal literary tourist, Dante, there are as many ups as there are downs. Also as with Dante, sometimes you offend someone in a position of power and get exiled; or, in Elsana-Alh’jooj’s case, have your car set aflame.

As it turned out, having her car torched was just one of the things that didn’t stop Elsana-Alh’jooj from pursuing a life defined by her refusal to be defined — by borders, by gender, by stereotypes of any kind or by other people’s expectations.

The book covers a journey that has taken her from a childhood herding sheep in her own Bedouin village in the Negev desert to a life of international activism for peacemaking and minority rights.

In the interest of full disclosure, I work for Elsana-Alh’jooj as a social media editor and writer at PLEDJ, the NGO she heads as the successor program to the McGill Middle East Program in Civil Society and Peace Building that first brought her to Montreal in 1997, and ICAN (International Community Action Network), which evolved from the MMEP.

In nearly every situation, her strategy is to get her own boots on the ground and ask the people involved what they need. Her approach is based on the idea that all human beings have the same rights, and the best action to be taken is in educating them about how to access those rights. This concept is at the core of everything that Amal does.

Because she is often described as a “force of nature”, working for her has been an adventure in piecing together a remarkable life from colourful digressions and generous, teachable asides squeezed in between work. So, I particularly appreciate Hope is a Woman’s Name for giving me context for many of the experiences I knew had informed her activism and her ambition for women, for Bedouin culture, and for peace. For the record, that time her car was set on fire happened because she married the man she wanted to marry — one of several times her vehicle was attacked as a signal that she should step back into line. A book has the space a conversation doesn’t. So, now I know how frightening it was every time, and the toll it took on her and her family.

Among my favourite stories in the book is the tale of the two lines. When she was a young girl, her grandmother passed on a lesson in how to navigate the world as a woman. She took Amal’s notebook and drew a line, saying that it was “the border of tradition”. Then she drew another next to it; that was “God’s border”. The space between the two was too narrow to easily walk, so as her sister puzzled, Amal drew two new ones, slightly farther apart. “There,” she said. “I made you new lines. Now you can walk between them easily.”

Though it was never quite that simple, Amal has spent her life finding a path between the existing lines and the ones she makes herself, sometimes through trial and error. In a particularly timely section of the book given both Quebec’s Bill 21 and the ongoing protests in Iran for women’s rights, much time is devoted to her eventual decision to wear a headscarf and all the considerations and events that influenced her final choice.

As an activist who had to navigate the political, religious and cultural minefield of Israeli-Palestinian and Israeli-Bedouin relations, she’s capable of a delicate balancing act when it comes to addressing deep-cut issues. Throughout the book, as in her TEDx talks, Amal gracefully tackles topics such as traditional cousin marriage without judgment or condemnation.

In a nod to her peacebuilding principles, the book begins with a note any student of the Middle East will appreciate — about “inconsistent” spellings, as most names in the region have at least two variants: Arabic and Hebrew. This inadvertently encapsulates the spirit of the book, the idea that differences don’t matter so long as you’re understood. The vocab lessons are fascinating: anything not asterisked was easily found online, and I found myself enjoying the hunt; the discovery of a new word for a concept I already knew or something brand new.

And regardless of potential linguistic barriers for the reader (or perhaps because of them) the prose frequently borders on poetry. The descriptions of locations and the emotions inspired both by and within them are so visceral that without having ever been to her village in an-Naqab, or the Negev desert, there are times when Amal’s descriptions are so vivid, you can feel the sand on your skin.

There are multiple recurring themes, but one thing that keeps popping up (in the book and in reality) is the cycle of oppression; the way that those who have been oppressed enforce those same barriers for others with less power. Hurt people hurt people, on every scale. From the perpetual cycle of conflict between Palestinians and Israelis, to the feedback loop of actions and expectations within patriarchal society. Amal herself admits to perpetuating misogyny by trying to toughen up her brother: “I wanted to protect him,” she writes, “to present him as having the kind of strength that our community associated with manliness so that he could survive a system that wasn’t kind to boys who were sensitive rather than senseless.”

She proposes a solution here, and it’s a more radical one in today’s world than it seems: talking to people. While it doesn’t always solve things overnight, and certainly not every issue, nearly every story in Hope affirms that it works. One especially heart-wrenching segment describes how Amal first discovered, after years of living on one side of the wall of disinformation between the Arab and Jewish peoples of the region, that the abstract enemy, the collective “other” is made up of human beings. While serving a field placement at a nursing home in a suburb of Be’er Sheva, she asked an elderly woman about her siblings. This slowly opened the floodgates to the Shoah survivor sharing her story. “It was my first encounter with someone who had survived the Holocaust,” Amal writes, “and it changed me, or rather, I should say, it opened me up to change.”

Hope is a Woman’s Name contains real, actionable lessons about how to approach community work, and goes above and beyond by presenting them in a way that’s not only interesting but beautiful.

As a personal memoir, the segments about Amal’s husband Anwar stand out: A running metaphor throughout is that of Amal putting her heart away in a jar in order to focus on her social work without the distraction of romance. When she first sees Anwar after years abroad but in secret communication, the sight of him in jeans and a long ponytail has her heart “dancing out of that jar”. There’s just as much love flowing from every paragraph about her twin children, her parents, her siblings, and every member of her family and tribe; even when she was making things difficult for them or vice versa. There’s also a tale about starting a sports day at a school in the desert, and the description of the donkeys all dressed up in their finery for a children’s race still prompts a smile.

Amal underscores throughout the book that she’s not the only character in this story, or even the protagonist. Her ideas could not have been translated into action without her drive, but nothing gets done without collaboration. The women in small villages who showed up to literacy classes, the young Bedouin men recruited from university coffee shops who showed up for protests, the other community volunteers and workers at outreach programs, and many others. Amal gives us her perspective because it’s the only one that she can, since, as she says, she learned long ago not to speak for or over others.

Hope is a Woman’s Name contains real, actionable lessons about how to approach community work, and goes above and beyond by presenting them in a way that’s not only interesting but beautiful.

Despite being steeped in the atmosphere and culture of the places our guide has walked through, the words are genuinely universal. One of the early pieces of wisdom shared with Amal is that the requirements for a person to be free are a saj, a tent, and a donkey. A saj, as the book explains, is a style of griddle for baking bread over a fire; a tent over her head, and a donkey for transport. The lesson is that food, shelter, and movement are not needs exclusive to the Bedouin or the Negev.

“We need more women like you.” Amal was once told, and it was and continues to be true. But perhaps a larger issue is that we already have plenty of women like Amal, whose stories aren’t told because they’re quashed: either the narratives, or the women themselves. Many are missing a happy ending simply because the focal character is still going. They need to be treasured and shared as much as possible.

You can learn more about PLEDJ here, and donate here.

Gray MacDonald is social media editor for Policy Magazine and for PLEDJ.