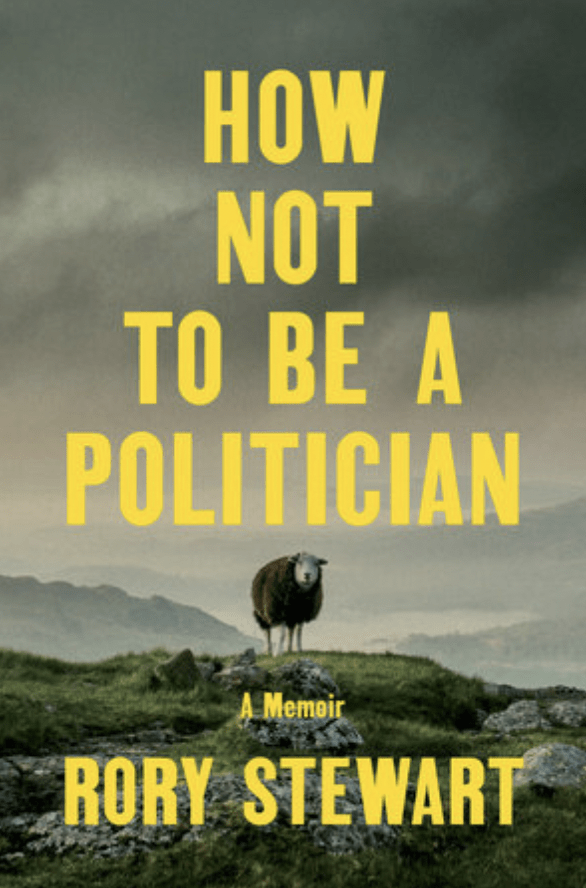

‘How Not to Be a Politician’: Rory Stewart’s Notes from the Trenches of SW1A

How Not to be a Politician: A Memoir

By Rory Stewart

Penguin Random House/2023

Reviewed by Peter M. Boehm

January 14, 2024

“We are trapped by the rigidity and shallowness of our political parties, the many weaknesses in our Civil Service, and the lack of seriousness in our political culture. We are trapeze artists, stretching for holds, on rusty equipment over fatal depths. A slip is easy.” Canada? No, the United Kingdom.

These are the words of Rory Stewart, four times a Conservative cabinet minister, once a failed prime ministerial candidate, a former diplomat, soldier and acclaimed writer known for recounting his walk across Afghanistan and his time as a provincial governor in Iraq. In telling us his story of an unconventional entry into politics from his essentially classic Eton/Oxford civil service background, Stewart accurately and compellingly describes the tense symbiosis between ministers and the civil service and the particular demands of constituency politics.

His remote former riding of Penrith and the Border — closer to Edinburgh than to London — is isolated and sparsely populated (he spent months walking his way through every hamlet in it). Stewart’s highly readable and often amusing journey of self-discovery exposes what he sees as incompetence, lying and outright nasty treachery — and that just within his own Conservative party. But the memoir also teems with policy analysis, ranging from international development (where Stewart and I connected in earlier incarnations), broadband infrastructure issues, to the British correctional service system, and of course Brexit.

In How Not to be a Politician: A Memoir, Stewart vividly chronicles turning the corner from his international life as a diplomat, Harvard professor, nomad and bestselling author to Tory backbencher: his efforts to secure the riding nomination, handling the barbs of the grizzled, ultra-partisan veteran MPs as a newbie and dealing with a very public profile, whereby he suffered the slings and arrows of social media that his friend Michael Ignatieff has attributed to “the digital disinhibition that turns people into vipers.”

He writes of his time not being his own, of voting in the House of Commons late at night, including the important “three-line whips” (a special term for Westminster aficionados meaning an order to show up and vote the party line or risk excommunication), being at the mercy of an always dubious if not cynical media and of ritualistic ministerial briefings from taciturn officials who calmly demonstrate their “learned helplessness”. He reflects on his work establishing and leading an NGO dedicated to restoration, education and health in Kabul as having been more satisfying than “the gripping of hands and putting on shit-eating smiles” that characterize active politics. Yet he persisted as an MP for over nine years, a minister for about half of that time, determined to do politics differently, to give back (as we all in the business righteously say), even when accused by pundits of being the archetypal politician.

Stewart’s highly readable and often amusing journey of self-discovery exposes what he sees as incompetence, lying and outright nasty treachery — and that just within his own Conservative party.

Mustering support quickly to be elected chair of the prestigious Defence Select Committee (highly unusual for a first-term MP but with significant support from Labour and the Liberal Democrats against some more recalcitrant ex-military Tories), Stewart led on reports calling for greater defence spending and more preparedness on European security following the Russian takeover of Crimea in 2014. He then moved on to junior ministerial roles as his aptly titled “Red Box” chapter indicates.

This period is characterized by endless briefings, budgetary cuts and shortfalls, anemic media strategies, the perpetual commissioning of studies and attempts by his alarmed civil servants, per the No-Minister reality of such dynamics, to restrain his urges to be a more “operational” minister. His varied portfolios allowed him to learn about the impact of climate change on flooding and agriculture in the UK, the apportioning of £13 billion in international development assistance, the prevention of drone deliveries of drugs into prisons — to name but a few issues — all while answering to parliament at the dispatch box in the House of Commons. Transitions between ministerial roles came overnight, policy and procedural learning curves were steep; officials always wary of their new minister, even when he had once been one of them.

Readers, like me, interested in international development will find Stewart’s description of his role and the activities of the UK Department for International Development (DfID) fascinating, particularly with respect to innovative approaches to official development assistance (ODA) occasioned by a tremendous legislated budgetary increase that committed the UK to 0.7 percent ODA to Gross National Income (GNI). During my time as deputy minister of international development I came to see DfiD as the global thought leader on trends, no doubt influenced by talented senior civil servants and enlightened ministers like Rory Stewart. Since his departure, the funding commitment legislation has been repealed and the department itself amalgamated into the Foreign Office.

Into all of this political activity the Brexit referendum bomb of June 2016 dropped. While Stewart had accurately forecast a 52/48 percent result in favour of the UK exiting the European Union, he was a devout remainer. With the resignation of Prime Minister David Cameron, Stewart became a stalwart supporter of his successor, Theresa May’s, approach to a negotiated deal and favoured a customs union as a way to handle the vexing “Irish backstop” problem as opposed to a “no deal” solution. With May eventually resigning over the defeat of her negotiated plan in parliament, Stewart emerged as a convincing and articulate purveyor of a realistic negotiated approach with the Europeans. At the same time, the power struggle for the Tory leadership allowed internecine rivalry to boil, with Stewart emerging as a strong succession candidate. Although Boris Johnson eventually grasped the brass ring, Stewart was, in contrast, a serious and principled contender. His chapter on the televised leadership debate, replete with arguments and counterarguments, including his selfless assessment of how and why he failed, makes for fascinating reading.

The book, like a Shakespearean play, includes a dramatis personae section. This is important because Stewart takes careful aim in mercilessly describing friends, colleagues and adversaries, some of whom — typically of politics — simultaneously fall into all three categories. His skewering of the more prominent Conservatives: David Cameron (“I divide the world between team players and wankers”), Liz Truss (“never be interesting, Rory”), Priti Patel (“among the word-flurries, her body remained preternaturally still”) is daring and funny. But he saves his best for Boris Johnson: “This air of roguish solidity, however, was undermined by the furtive cunning of his eyes, which made it seem as though an alien creature had possessed his reassuring body and was squinting out of the sockets.” With descriptions like these and many others, it is unclear to me whether Stewart could or would want to make a political comeback, regardless of his youth and the popularity of his books and podcast, The Rest is Politics, co-hosted with Blairite comms guru and former journalist Alastair Campbell.

What is clear throughout the book is Stewart’s love of his country (including Scotland), its institutions and its place in the world. He has written a riveting and stylistically brilliant memoir that explores politics from the perspective of a very human practitioner. Would that we were all more like him.

Sen. Peter M. Boehm is a former career diplomat and deputy minister. He chairs the Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade.