‘How Will It Play in Drumheller?’ Brian Mulroney and Free Trade

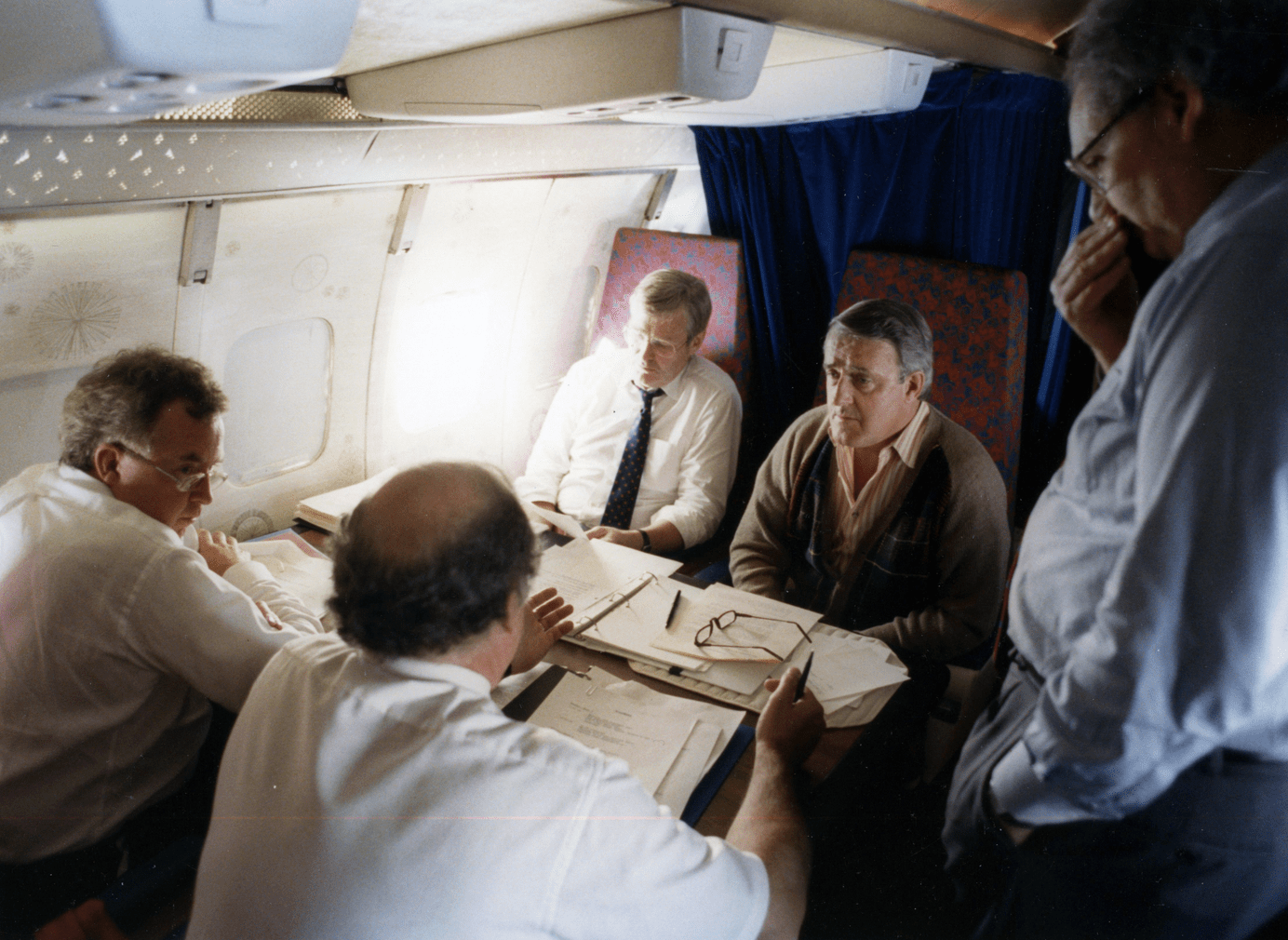

Derek Burney advising Prime Minister Brian Mulroney during a flight in 1988, the year a federal election was fought and won on free trade with the United States. Clockwise: Finance Minister Michael Wilson, the prime minister, Chief of Staff Stanley Hartt (standing), Burney and External Affairs Minister Joe Clark/Bill McCarthy

Derek Burney advising Prime Minister Brian Mulroney during a flight in 1988, the year a federal election was fought and won on free trade with the United States. Clockwise: Finance Minister Michael Wilson, the prime minister, Chief of Staff Stanley Hartt (standing), Burney and External Affairs Minister Joe Clark/Bill McCarthy

By Derek Burney

March 12, 2024

Among the many achievements that made Brian Mulroney our most consequential prime minister in the last century was his bold move to conclude a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the United States, followed by NAFTA, which brought Mexico into the pact. The mere concept of free trade with the US was a political bogeyman for many, especially English Canadians who were fearful that their culture and their economy would be swamped irreparably. Decades of branch-plant manufacturing did not help, cossetting industrial parts of Canada from the dynamism of competition while simultaneously stunting our growth prospects.

When he first ran for the P.C. leadership in 1976, Brian Mulroney was firmly opposed to free trade with the US, in line with his party’s history. The Liberals were generally more favourable to the idea than Conservatives.

I was often asked why Mr. Mulroney changed his mind on such a potentially divisive issue. I did not discuss his reasoning explicitly with him, but I was sure there were several compelling factors. First, the economy was sputtering in the early 1980’s with low investment and even less technological innovation, causing the Trudeau government to launch a Royal Commission on Canada’s economic prospects, headed by former Finance Minister, Donald Macdonald. The study released in the fall of 1984 proposed that Canada take a “leap of faith” on free trade as a dramatic way to shake the cobwebs out of the Canadian economy. The Commission provided the analytical underpinnings for the initiative and Macdonald’s name gave it bipartisan political gloss.

Simon Reisman, a prominent Canadian trade negotiator who had served as deputy minister of Finance to Opposition leader John Turner, added his own imprimatur in what some called the “best job description ever” with a crisp, 10-page memo to the prime minister outlining why and how a free-trade negotiation should be advanced. He got the job.

Finally, Ronald Reagan was known as an ardent free trader and, as such, was seen as a partner with whom Canada could do business.

Following the Shamrock Summit decision to launch negotiations in March 1985, Canada made substantial structural moves for a major trade negotiation. Simon Reisman headed the new Trade Negotiation Office (TNO) reporting to a special cabinet committee headed by the Deputy Prime Minister, Don Mazankowski. This was intended to cut through bureaucratic resistance or inertia.

There was by no means universal support for the initiative in many departments. Reisman envisioned a big agreement. He recruited Gordon Ritchie – a tough and seasoned individual ideally suited to subduing bureaucratic infighting — as his deputy. Top trade negotiating talent was also recruited from the departments of External Affairs and Finance.

Unfortunately, the Americans did not respond in kind. They set up an ad hoc interdepartmental committee from various departments headed by a second-level official from United States Trade Representative (USTR), who had limited political access or influence and focused essentially on a laundry list of American irritants with Canada.

As the negotiations plodded slowly for months with minimal progress, frustration mounted in Ottawa. As PMO chief of staff, I prodded my counterpart in the White House, Howard Baker, to inject some political oversight into the effort, noting that our prime minister was investing considerable political capital in the initiative. The prime minister prodded Ronald Reagan tactfully every time they met but to no avail.

Ultimately, with full cabinet support, Simon declared, near the end of September, 1987, that the negotiations were suspended because the Americans declined to consider Canada’s bottom- line position. We wanted a binding dispute settlement mechanism to protect us from arbitrary US “trade remedy” actions – our bête noireon trade with the US and to temper the economic and political power imbalance between the two countries.

Some Americans interpreted Simon’s move to be a bluff. Howard Baker called me and urged us to return to the table. I said that there was no point reconvening if there was nothing on the table that responded to our principal demand. We sensed that the Americans seemed convinced that Canada would accept virtually anything – a deal focused on tariff reduction – ours being generally higher than theirs. We had to disabuse them of that notion.

The October 3 deadline on which the administration needed to gain “Fast Track” negotiating power from Congress — i.e. for a vote up or down and with no amendments — was fast approaching.

I had carefully rehearsed my message with the prime minister at the airport before we left. What I said, in effect, was ‘the deal we want, we do not see, and the deal we see, we do not want.’

It really seemed that the negotiations were over, and on October 1, I was dispatched by the prime minister, along with Finance Minister Mike Wilson and Trade Minister Pat Carney, to confirm formal termination face-to-face with the political level in Washington and to plan a salvage effort.

Mr. Mulroney had instructed me to lead our trio and I had carefully rehearsed my message with the prime minister at the airport before we left. What I said, in effect, was “The deal we want, we do not see, and the deal we see, we do not want.” It fell short of what we wanted in terms of relief from negative US trade remedy action. Experience with shakes and shingles, softwood lumber and steel in the early 1980s had driven this lesson home to us in spades.

Improved productivity by Canadian firms was seen as an essential by-product of trade liberalization and there was confidence that Canadian industry and exporters could compete effectively in the US. market if the ground rules were clear and fairly administered. We needed to ensure that Canada’s position as a magnet for investment was competitive with that of the US. With increased investment would come increased production in Canada and new technologies to provide good, market-driven jobs not based on government subsidies.

Our basic belief was that, if Canadian companies expected to succeed more broadly in global markets, they had to first compete in markets next door.

Much effort had been expended trying to draft rules that would enshrine the interrelated issues of dispute settlement and trade remedy relief. None had passed muster. The main problem was that Canada was far more dependent on trade than the US, which relied on its own huge market for much of its economic growth. Any imaginable formula on “trade-distorting” subsidies would hit Canada harder than the US.

Congressman Sam Gibbons, a Democrat from Florida and chair of the House Ways and Means Subcommittee was an ardent free-trader and well-disposed to Canada. He suggested that the two countries develop a bi-national dispute settlement mechanism to ensure that implementation of each sides’ existing trade rules were being respected on their merits. It fell short of agreed rules on competition and government subsidies but would at least temper the application of discriminatory trade remedies. The existence of impartial referees should inhibit capricious behaviour. Gibbons’ concept rapidly became the kernel of a solution.

Secretary of the Treasury James Baker, who had taken charge in Washington, took soundings on Capitol Hill, notably with Chicago Democrat Dan Rostenkowski, chair of the Ways and Means Committee, which had jurisdiction over trade agreements. Baker called me to say the US. was prepared to consider “something like the Sam Gibbons formula” if that would bring us back to the negotiation.

I relayed that exchange to the prime minister, who invited me to brief the cabinet on the pluses and minuses of the agreement we might get. The ensuing debate was anything but unanimous. After hearing a litany of discordant views, the prime minister concluded, saying in effect, “Derek, you know where matters stand.” I then went into a marathon session with Simon and his TNO team to get a complete account of where the negotiations had ended.

We met in Washington on October 2, heard reports of the state of play from both sides and determined whether and how to deal with outstanding elements. Some differences were set aside for more work; others were resolved at the table.

There were flashes of fire and frustration from Baker at Mike Wilson over financial services, and from me to all the Americans over intellectual property (patents for pharmaceuticals).

Despite the occasional theatrics, we made good progress on most items, but Dispute Settlement remained elusive. I met Secretary Baker alone on the morning of October 3, signaled our willingness to move on financial services – restrictions on US investments in Canada (his priority) – but only if the dispute settlement issue, which was a sine qua non for Canada, was resolved to our satisfaction. Baker was facing significant protest from his legal advisors that such a mechanism would intrude on US sovereignty.

When nothing materialized by about 7 pm, I phoned the prime minister and advised him that we still had no agreement on our key point. “So be it,” he replied. He instructed me to tell Baker that he wanted to telephone President Reagan; not to cajole, but to confirm that the negotiations were over. As the president was not available, Mulroney called Baker instead to register his astonishment that the US could conclude an arms control agreement with their ardent foe, the Soviet Union – but could not conclude a trade agreement with their neighbour and ally, Canada.

At about 8 pm, I called the prime minister again and he said he would leave Harrington Lake, head to the Langevin building and announce that the negotiations had failed.

One hour later, Baker burst into his anteroom (which we were using as our office), flung a piece of paper on the desk and declared, “All right, there is your goddamn dispute settlement mechanism. Now, can we send the report to Congress?” On reading his note, we nodded in agreement.

I called the prime minister and said, “I believe we have an agreement after all.” He was surprised and undoubtedly relieved. He asked whether we all concurred that the agreement met his basic objective – that Canada would be “significantly better off with it than without.” I polled my inner team of eight – Mike Wilson, Pat Carney, Simon Reisman, Allan Gotlieb, Gordon Ritchie, Stanley Hartt and Don Campbell – and the verdict was unanimously positive. (I had been adamant all along that no deal was better than a bad deal and had insisted each member of our core team approve or reject all key elements.)

With Brian Mulroney’s second majority win in 1988, the negative stigma associated with free trade in Canada mostly disappeared.

Then, Mr. Mulroney stumped me. “So, Derek, how will it play in Drumheller?” “Well,” I stammered, “it is good on energy and on red meat so I assume it will go down well in Drumheller.” “That’s great,” he said, and then conveyed his thanks to each team member individually.

The result was, as Jim Baker acknowledged in his memoir, a “near-run thing” but happened because political will was ultimately galvanized on both sides.

Much still needed to be done, but the term-sheet agreement broke the impasse, enabling the drafting of a full legal text and approval by our Parliament and the US Congress. Once this was done, the agreement was signed formally by the president and prime minister on January 2, 1988, setting the stage for a major political battle in Canada leading up to the November 21 election.

Prime Minister Mulroney took a major risk. He firmly believed that the agreement would be good for Canada and would be key to his attempt to refurbish relations with the US. He gave full authority to his negotiating team. He was remarkably sanguine about the prospect of failure, but his confidence and conviction provided the essential rudder during the ups and downs, the tensions and turmoil of the negotiations and the election campaign.

The positive trade results speak for themselves. In the first decade after the FTA, Canada’s exports to the US. more than doubled, as did US. exports to Canada. A real “win, win.” The Dispute Settlement Mechanism was emulated in NAFTA, at the WTO and in several other free trade agreements. But, most convincing of all, many of the most vehement critics of the agreement, including Liberals Brian Tobin and Sergio Marchi, openly acknowledged after the fact that they had been wrong.

With Brian Mulroney’s second majority win in 1988 – the first back-to-back majorities for a Conservative since John A. MacDonald – the negative stigma associated with free trade in Canada mostly disappeared.

When Donald Trump tried to dismantle the agreement’s successor – NAFTA – the government and Parliament united in their efforts to thwart his intent, abetted notably by Mr. Mulroney himself and key members of his negotiating team.

In my view, the free trade initiative was the consequential act of political courage by a prime minister who refused to be hobbled by history and was emboldened by his confidence in Canada’s future. He was tenacious in pursuing the initiative, withstood prolonged indifference from the US administration and furious, partisan, often irrational attacks at home.

Political leadership is not for the faint of heart.

Derek H. Burney was Chief of Staff to the Right Honourable Brian Mulroney from 1987-1989 and Ambassador to the United States from 1989 –1993.