Inflation, Politics and Economic Resilience

Kevin Page with Alexandra Ducharme

November 26, 2021

The Speech from the Throne (SFT) for the First Session of the 44th Parliament of Canada was delivered on November 23rd. The title was Building a Resilient Economy. Economic resilience is commonly defined as the capacity of the economy to resist a particular shock and recover. Can the Canadian economy resist and recover from the inflationary impacts stemming from the COVID-19 global pandemic policy response?

Yes, but it will take policy discipline from both our central bank and federal government to anchor inflation expectations. We need both the governing and opposition parties to raise their policy game for Canadians. The economic stakes are high.

Management experts tell us that managing risk is different in practice than managing strategy. Inflation needs risk management that focuses on negative possibilities. Public policy priorities highlighted in the SFT need managing strategies that focus on positive possibilities – a carbon neutral economy, greater inclusion, safe communities, and reconciliation for First Nations people and true well-being for their children.

Financial stability and stable inflation are important means to an end. The policy objectives (or ends) are sustainable growth, inclusion and resilience. High and rising inflation rates have the potential to undermine and de-stabilize growth. If wages fall behind price growth, improvements in standards of living of workers will slow. If inflation rates spike, our central bank could be forced to raise interest rates significantly which will disrupt economic recovery. High and rising inflation creates uncertainty that can slow business investment necessary for future growth and transition to a carbon neutral economy.

It will take policy discipline from both our central bank and federal government to anchor inflation expectations. We need both the governing and opposition parties to raise their policy game for Canadians. The economic stakes are high.

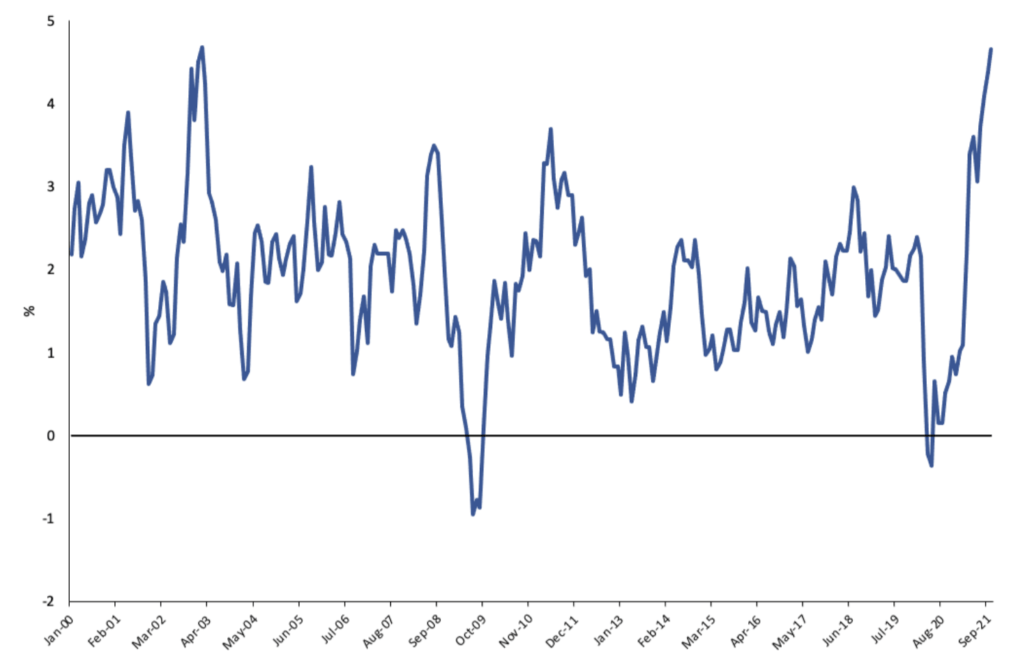

Consumer price inflation is on the rise (Chart 1). The consumer price index (CPI) was up 4.7 percent on a year-over-year basis. The increase in the year-over-year rate of increase has been quite steep since last summer. This is not the first time over the past 20 years we have seen inflation spike above the Bank of Canada’s 1 to 3 percent range but the trajectory and level is waking up policymakers. Google searches about inflation in Canada have risen dramatically, highlighting broad based attention and concern.

Chart 1 – Consumer Price Index Since 2000, Year-over-year percent change

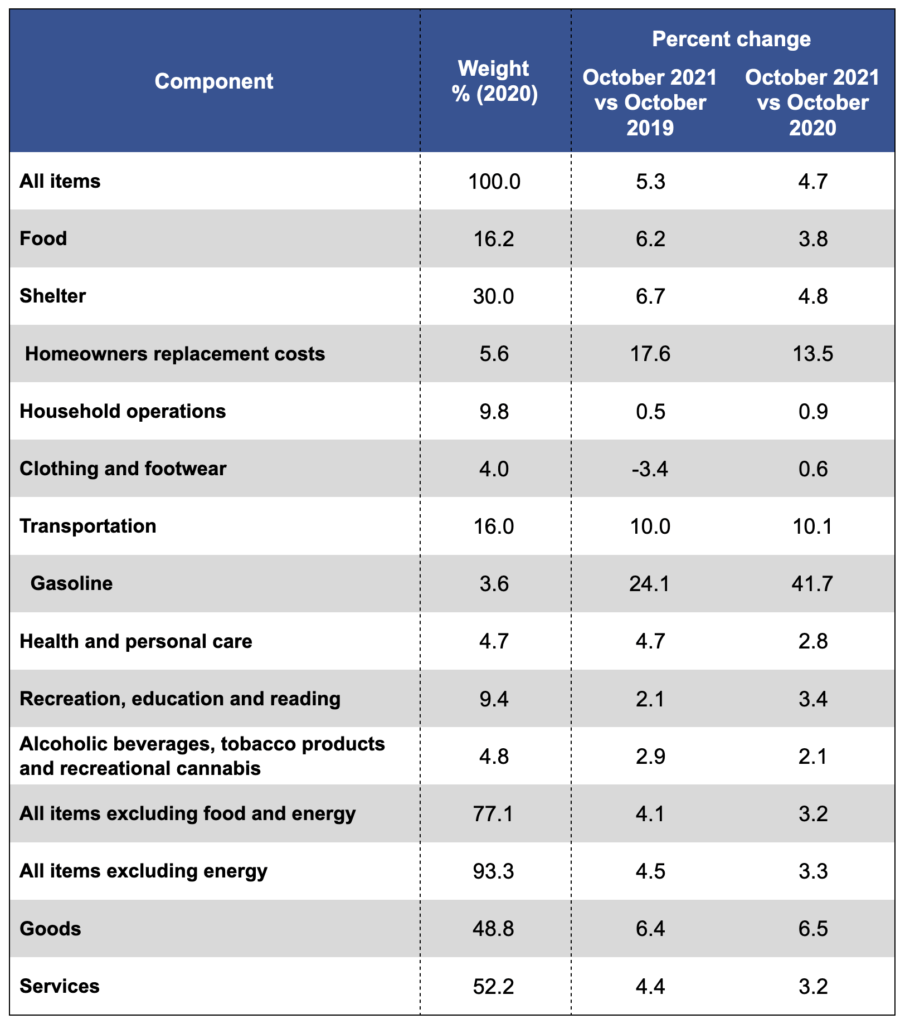

Table 1 indicates that the rise in the CPI over the past year has been largely driven by two components – shelter (particularly homeowners replacement cost; up 13.5 percent) and transportation (particularly gasoline; up 41.7 percent).

The cumulative increase in the price level over two years is 5.3 percent. This is an average of little more than 2.5 percent which would lie within the Bank of Canada target range of 1 to 3 percent per annum. This metric helps smooth the fluctuations of price deflation during the economic lockdown in the spring of 2020. The two- year metric also picks up the surge in food prices in 2020.

Table 1 – Consumer Price Index Since 2019

The policy concern that the current spike in the CPI inflation rate may be more persistent than transitory largely comes from other price inflation metrics. The Industry Price Index was up 14.9 percent in September on a year-over-year basis. The Bank of Canada Commodity Price Index was up 56.8 percent in October on a year-over-year basis. The increases in both of these indices reflect higher energy and non-energy prices and raise concern of further price pass through in the year ahead to the consumer.

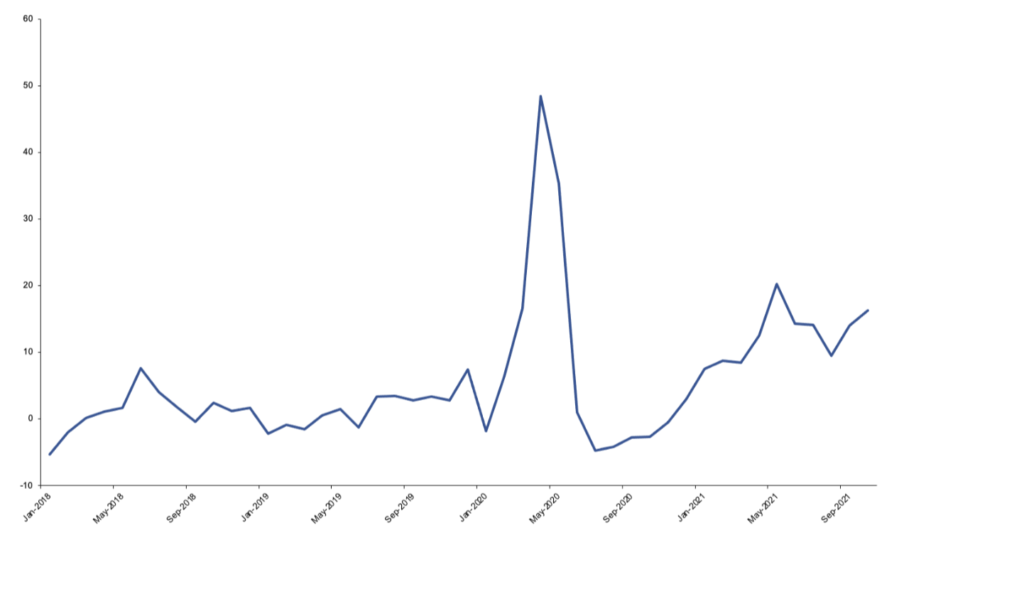

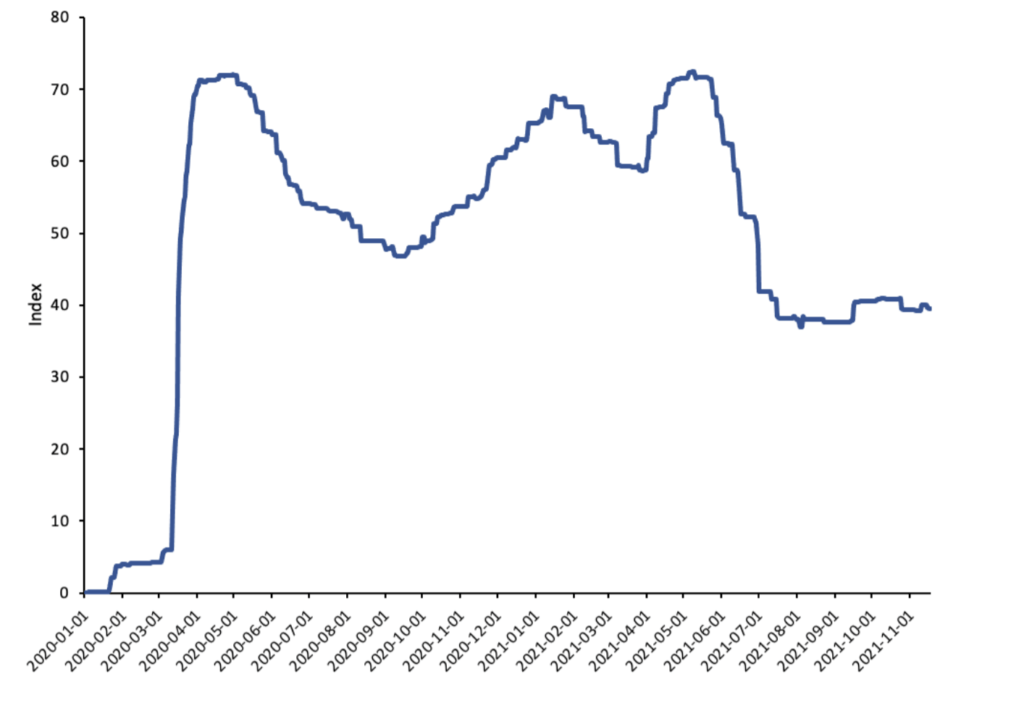

The underlying dynamics of the increase in price inflation are related to three factors – supply-demand adjustments in energy markets after the global lockdown, global supply disruption (Chart 2); and the demand pull of an economy opening up (Chart 3) with vaccination progress and relatively healthy household balance sheets (Chart 4) thanks to historic federal government transfers.

Chart 2 – ISM US Managers Purchasing Managers Index (PMI): Supply Disruption Index

Note: Supply disruption index is measured as the difference between supply deliveries to manufacturers and production. Suppliers to manufacturing industries reporting ongoing supplier hiring challenges, extended raw materials lead times for all tiers, increasing levels of input material shortages, stubbornly high prices and inconsistent transportation availability.

Chart 3 – Bank of Canada COVID-19 Stringency Index

Note: Measures the severity of government containment policies and public information campaigns in Canada

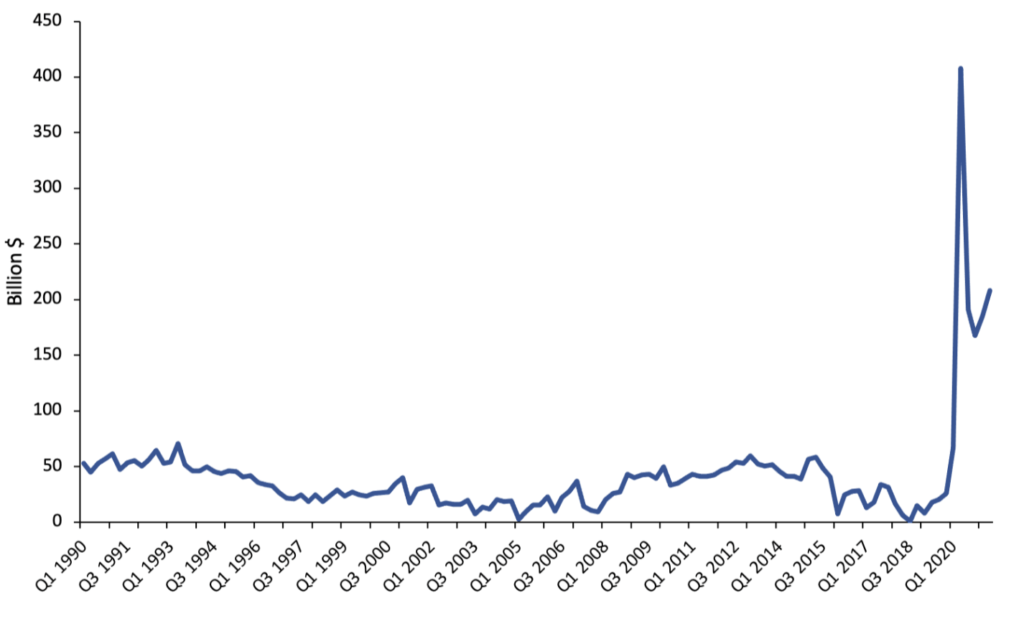

Chart 4 – Household Net Savings, National Income Accounts

It is worthy of note that notwithstanding the steep rise in the inflation rate in 2021, most indicators on the health of household balance sheets are in better shape relative to levels prior to the COVID-19 pandemic including consumer credit and mortgage liabilities relative to disposable income and household savings rates. This positive outcome reflects low interest rates, historic increases in government transfers and a cut back in spending during the lockdowns.

While policymakers take comfort in the strength of household balance sheets after a drawn out and ongoing public health crisis, there is the concern that pent up demand will push up prices further in the months ahead with ongoing supply bottlenecks.

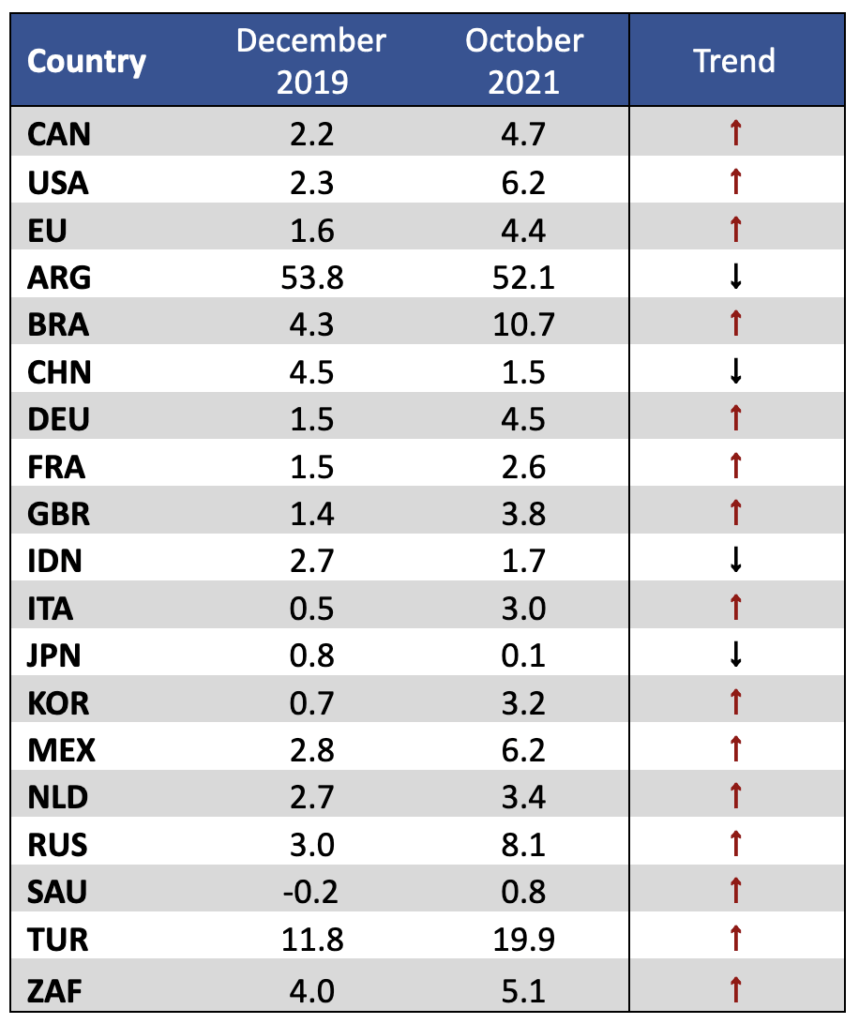

Canada is not alone with respect to higher price inflation. Data from the OECD indicate that almost all advanced countries have experienced doubling of year-over-year inflation rates since the start of the pandemic (Chart 5). Countries like the US and Canada that have had relatively large fiscal supports during the COVID-19 period have experienced relatively higher year-over-year inflation rates.

Chart 5 – International Comparison of CPI Inflation Rates, Year-over-year percent change

Is Canada at a pivot point with respect to the trajectory of inflation? Over the past 20 years (Chart 1), when we have seen the CPI rate of inflation go above the Bank of Canada 1 to 3 percent target range, we have seen special factors unwind because of adjustments in global markets for energy and/or changes in government monetary and fiscal policy (i.e., less accommodative or stimulative policies).

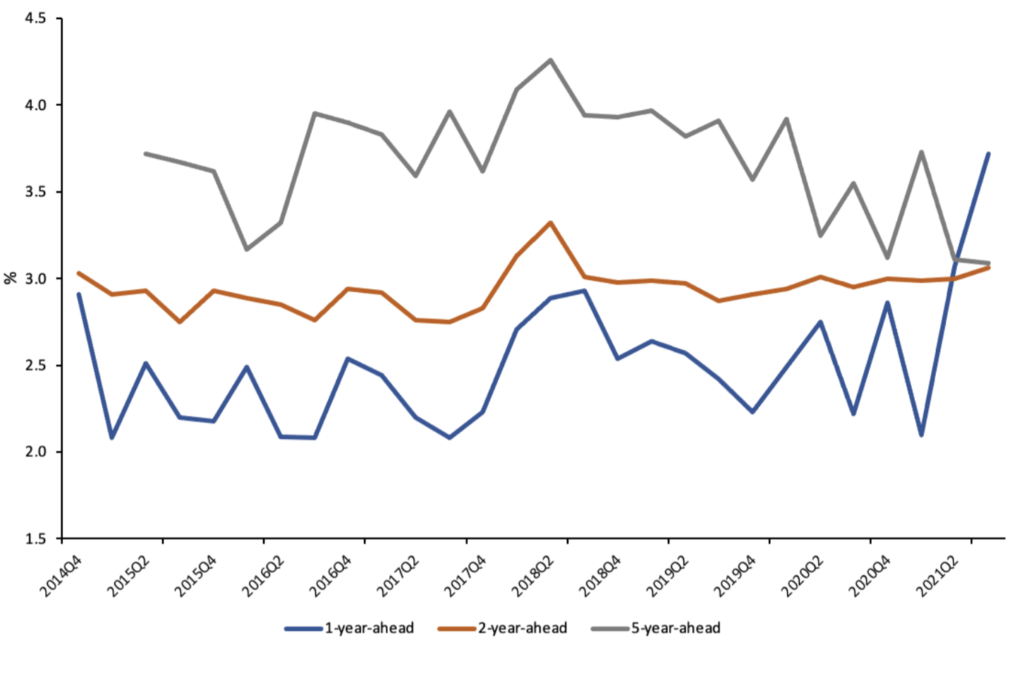

Bank of Canada surveys on consumer expectations of inflation (Chart 6) add support to the argument that we are at a crucial juncture with respect to anchoring inflation expectations. Consumers are locking in expectations for higher inflation over the short term. They have not yet adjusted their expectations for the medium to long term.

While policymakers take comfort in the strength of household balance sheets after a drawn out and ongoing public health crisis, there is the concern that pent up demand will push up prices further in the months ahead with ongoing supply bottlenecks.

If consumers and businesses do adjust their longer term expectations, the hope for a short term transient surge of inflation in a post COVID-19 recovery could be lost to a battle of increasing inflation rates with the risk of stagflation (higher inflation and weak employment) and potential economic destabilization as the central bank in Canada is forced to significantly raise interest rates to lower inflation.

Chart 6 – Bank of Canada Survey of Inflation Expectations, Consumer Price Index

We need to push our government and opposition parties to raise their game in the risk management of inflation.

The Government position reflected in the SFT is that the recent inflation surge is global in nature and that their policies to increase the affordable housing supply and make child care more affordable is sufficient.

The Official Opposition position that higher inflation is largely generated by the current government.

Neither position is satisfactory.

In a rising inflation rate environment stemming in large part from global supply disruptions but also large fiscal supports (which increased aggregated household net savings) it is very important that governments (and central banks) do their part in anchoring inflationary expectations. For the government, this includes fiscal rules like declining debt-to-GDP ratios; declining nominal budgetary balances, ample prudence reserves around budgetary balance projections and forward guidance on spending including targets for public sector wage compensation growth.

The government should reconsider fiscal guardrails on stimulus-style spending, as highlighted in the Fall 2020 Economic and Fiscal Update, so they have the appropriate budgetary stance both in size (relative to the economic cycle) and structure (between consumption and investment). This fiscal stance should be analyzed by the independent Parliamentary Budget Officer (i.e., short term impact on output growth and inflation; consistency with fiscal rules; long term fiscal sustainability) and discussed and debated in Parliament as is the practice in most European Union countries.

The Official Opposition has the opportunity and responsibility to ensure future spending promotes longer term growth through capital investment (physical, human and environmental) and the investments are supported with analysis such as a national infrastructure needs assessment as was highlighted by the government in Budget 2021 (but not in the SFT) and has been used in both the United Kingdom and Australia.

Contributing Writer Kevin Page is President and CEO of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa. He was previously Canada’s first Parliamentary Budget Officer.

Alexandra Ducharme is a fourth-year economics undergraduate student at the University of Ottawa.