Is Neutral Nearly Enough?

Douglas Porter

April 15, 2022

The phony war on inflation ended with a bang this week, as central banks began rolling out the big guns. After a few opening 25 bp salvos last month, this week saw the first 50 bp hikes by an advanced-economy central bank—first from New Zealand, and then hours later from Canada. From our records, these were the first such half-point hikes by any major central bank in twenty years, and were essentially an admission that conditions had been left far too loose for far too long. These will likely not be the last 50 bp moves this tightening cycle from these two banks, and they are almost certainly not going to be the only ones in the half-point pool. To wit, markets are almost fully priced for a 50 bp move by the Fed on May 4, a step reconciled by even long-term doves.

The need for speed became even clearer this week amid another flurry of super-sized inflation readings from near and far. U.K. inflation hit 7% in March, and nearly 12% at the producer level. Sweden’s CPI rose 1.8% in a month. Not to be out-done, Germany confirmed consumer prices soared 2.5% m/m, lifting the annual inflation rate to a towering 7.6%, in a nation where inflation averaged 1.4% in the prior 25 years. U.S. headline CPI famously hit a 40-year high 8.5% y/y pace last month, and producer prices clocked in at a furious 11.2% y/y clip. Those meaty results made few market waves, as core CPI rose “only” 0.3% m/m, in what passes for good inflation news these days. It’s probably impolite to point out that the “low” reading was flattered by a 4% drop in used car prices, and that the rest of core rose 0.55% (or a 6.8% annual rate).

So, forgive us for not seeing a 6.5% y/y pace for core CPI as a reason for Fed relief. Still, the U.S. core read was enough to temporarily take some steam out of rate hike views—two-year Treasury yields dipped 7 bps this week, helping re-steepen the curve as 10s hit 2.80%. After the frenzy of concern around the temporary inversion two weeks ago, the 2s10s spread fattened out to 37 bps by Thursday, well out of the danger zone for the economic outlook. Canada’s curve pulled a similar trick, with two-year yields nudging lower this week (even with the 50 bp hike) and 10s stepping higher, widening the gap to above 30 bps.

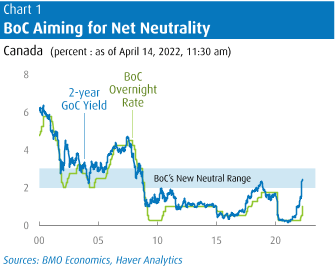

The lull in two-year bond yields does nothing to detract from the bigger picture—the pressing need for central banks to get policy rates back to neutral as quickly as possible. That is, as fast as financial markets and the economy can manage. For the Bank of Canada, that means pulling the rate up from 1% now to their new neutral range of 2.0%-to-3.0% (freshly revised up by 0.25% on both ends). The Fed is a little less explicit, but the mean estimate of the long-run rate from the dot plot is just above 2.4%, so remarkably similar to the BoC’s mid-point estimate. At a bare minimum, this implies another 100 bps of tightening by the BoC in short order, and about 150 bps from the Fed, just to get to the very low end of the range. In both cases, two-year yields are already essentially at the neutral mid-point (Chart 1).

But this raises two pressing questions: 1) As per the title, will that be enough to do the job of controlling inflation? And, 2) can the economy handle such a rate hike fusillade?

On the first question, we suspect the answer is “not quite enough, no”. At this point, we are expecting that rates will need to ultimately go a little above the mid-point of neutral to bring inflation to heel. That also means that they will need to go above the peaks of the prior tightening cycle. But, still, overnight rates of just under 3% may look insubstantial when stacked up against consumer price increases rising at triple that pace. However, there are at least four reasons to believe that this may be just enough to do the job:

- The rate hikes will be much faster than previous cycles.

- They will be twinned with aggressive QT.

- Fiscal policy (in both the U.S. and Canada) will go from a sprint to a walk.

- Supply chain issues will improve, supported by a shift back to services spending.

That is not to say we are at all relaxed on the inflation outlook—we remain at the very high end of consensus on the CPI forecast over the next year. Bubbling wage pressures, a shifting inflation mindset among consumers, and still-strong commodity prices suggest stickiness. But even we expect that these combined forces should carve underlying inflation back toward 3.5% in both economies by next year. We are also coming around to the view that—barring another serious spike in oil prices—March may indeed mark the peak for inflation in this cycle. (Canada’s CPI is the main event next week, and it is expected to lurch up 1% m/m, boosting the annual rate to 6.2%.)

But that brings us to question 2—will the economy withstand the rapid blast of rate hikes required to tame inflation? That is an issue that can’t be fully addressed in the short space on offer here, but our short answer would be “just so”. Notably, the Bank of Canada seems in no doubt that growth can readily hold up to a wave of tightening—the Bank actually boosted its GDP estimate for 2022 in its latest quarterly forecast to 4.2% this year (from 4.0%; we are at 3.5%). The BoC may well be the only major central bank in the world that has revised its growth outlook up in the wake of the Ukraine invasion. The Bank’s MPR methodically went through the additions and subtractions to growth from the conflict, and found it to be a net neutral for Canada; the upside revision reflects the fact that the economy weathered the Omicron storm better than expected in Q1. However, at the same time, the Bank also trimmed its call on 2023 growth to 3.2% (from 3.5%) and has initially pegged 2024 at a mild 2.2% pace, both of which may reflect more rate hikes than previously expected.

The BoC has a generally more upbeat view on things than we do for 2022/23, but the main point is even relatively cautious forecasters are still penciling in above-average growth this year and next. The challenges are clear—a chillier and more volatile global growth backdrop, a housing market coming off the boil, less forceful fiscal support, and wages trailing fiery inflation. But recall that there are also two special factors which are likely to provide strong underlying support:

- There is still a deep well of pent-up demand, for travel, entertainment, and other services, as well as for some big-ticket items that simply could not yet be secured (e.g., vehicles).

- There is still a deep well of pandemic savings to be drawn upon to fund this pent-up demand, even if the price tag has gone up mightily.

The many moving parts for the economy in the past two years have humbled forecasters, so we can only say growth will likely prove resilient in the face of rate hikes. There’s also the reality that central bank hikes may be somewhat less fierce if the economy struggles—i.e., their bark may yet prove to be worse than their bite. But the barking is very noisy indeed.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.