Israelis, Palestinians and Democratic Peace Theory

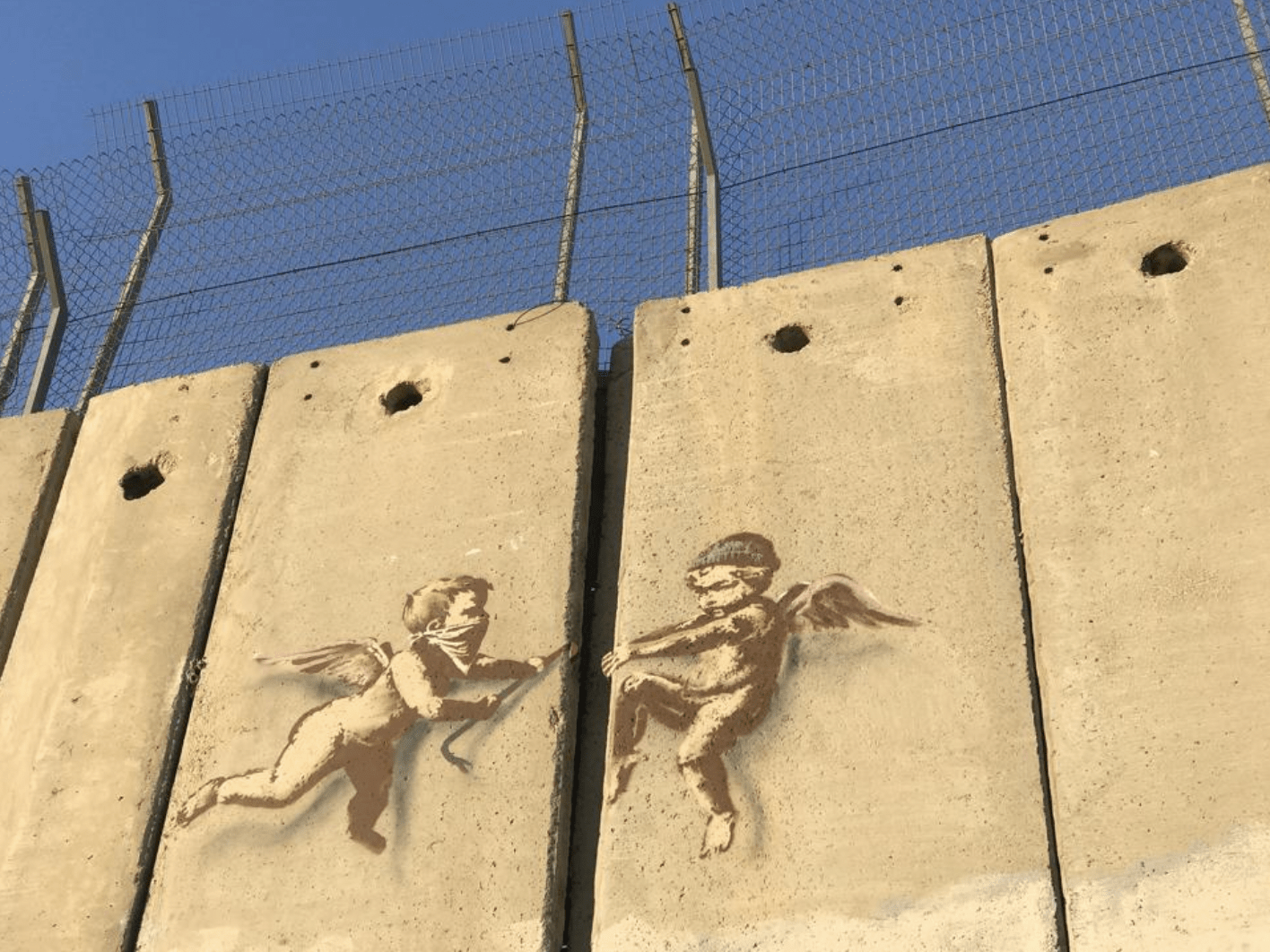

Banksy’s Bethlehem artwork/Forbes

Banksy’s Bethlehem artwork/Forbes

By Lisa Van Dusen

November 29th, 2023

Years ago, I worked for a Middle East peace building NGO during the post-Oslo, pre-Hamas period of disappointment and hope. It was an experience graced by regular reminders that the people on both sides of the conflict shared so much more than the political headlines ever betrayed. There were times in meetings when, if you’d just walked in and started listening, you wouldn’t have known whether the speaker was Israeli or Palestinian.

Those moments were brought back recently, on a day when the truce between Israel and Hamas in the latest, most horrifying, explosion in the conflict stopped the killing and saw the return of Israeli hostages and Palestinian prisoners to their families. Both sides were dancing in the streets, on the same day — a first in recent memory.

Democratic peace theory holds that democracies are less likely to go to war with each other. As a widely accepted precept of international relations whose origins date to Immanuel Kant’s 1795 work, Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch, the notion that democracies are less aggressive, especially toward other democracies, has stood the test of time despite the rare, infinitely argued exceptions that prove the rule.

(The fact that the US Civil War is cited as one of those exceptions says more about the enduring denial of slavery as a glaring asterisk to democracy than it does about the validity of the exceptions).

In the case of Israel’s war on Hamas, the theory is nuanced by three factors.

First, the democratic status of the two belligerents is not what it would have been if the experiment in Palestinian democracy that began in 1996 had not produced the 2006 Hamas victory in Gaza. That result divided the Palestinian leadership between Hamas in the strip and Fatah in the West Bank, and provided Israeli hawks with a convincing rationale for mothballing the peace process aimed at a two-state solution.

Second, the democratic status of the two belligerents is not what it would have been if Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had not spent the 15 years since he returned to the job a decade after he lost it in 1999 undermining Israeli democracy through an unprecedented tactical siege of the office against all competitors, judicial threats and electoral conventions. That power consolidation campaign had produced the most sustained popular backlash against any Israeli prime minister since the country’s founding when the nightmarish events of October 7th drastically disrupted the region’s political narrative.

Third, except for a tentative respite during the mid-90s before the progress of Oslo was blown-up by Camp David II and the Second Intifada, Israel and the Palestinians have been in a permanent, default state of conflict since 1948. Within that context, the eruption of generational, border-altering wars, intermittent military operations and sustained terrorist attacks between the two parties has trumped their systemic status for 75 years.

But the reason democracies generally don’t go to war with each other — a proposition endlessly argued in survey courses but essentially sound, with the absence of war between democratic states recognized as all-but empirical law in international relations — isn’t a mystery.

Among other shared characteristics, Israelis and Palestinians have become more adaptable, more resilient and stronger than any human beings should ever have to be.

Democratically secured and ratified political power depends on the will of the people, and people generally don’t approve of infant decapitation, rampaging medieval massacre, the targeting of hospitals, hostage taking, the murder of children and the blockading of food and water as weapons of war. As Michael Ignatieff, former Liberal leader and founder of the Carr Center for Human Rights at Harvard, wrote in a piece on the Geneva Conventions for The Atlantic published October 27th, Israel “has always distinguished itself from adversaries by its status as a democracy,” which situates its comportment in war within the accountability of democracy, even in prosecuting a legitimate casus belli.

It would be tempting to minimize the precedents above based on the propaganda-fed delusion that they no longer matter in a world where it now seems anything is possible. That delusion has served the interests currently degrading democracy worldwide more efficiently than just about any other narrative warfare weapon. In reality, Israelis and Palestinians are now living through an extreme version of a role they’ve been playing for decades — that of teaching the world how to live amid perpetual conflict and violence, especially when intractability becomes a bilateral political commodity.

The truism that Palestinians and Israelis share a genetic provenance may be less pertinent than the shared epigenetic skills that human beings on both sides have developed via nurture rather than nature over nearly eight decades of constant stress, constant loss, constant fear, perpetually elevated cortisol levels, politically leveraged moral complexity and parallel existential uncertainty. Among other shared characteristics, Israelis and Palestinians have become more adaptable, more resilient and stronger than any human beings should ever have to be.

Those qualities, which the world has witnessed among Israelis since the Hamas atrocities of October 7th and among Palestinians since the Israeli military’s scorched-earth retaliation operation started, have provided — as always, at incalculable cost — yet another shared experience belying the manufactured divisions, physical and otherwise, that have defined their inextricably enmeshed political drama. When this war ends, or better yet before then, UNESCO should add Palestinian and Israeli fortitude to its Intangible Cultural Heritage list.

As neighbours now both living through democratic deficits with predictable kinetic results, Israelis and Palestinians have shared both the horror of war and the joy — if fleeting — of peace. Their leaders more than owe it to them to prove they know which one is better.

Policy Magazine Editor and Publisher Lisa Van Dusen was a Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington. She also served as director of communications for the McGill Middle East Program in Civil Society and Peace Building.