Kissinger on Leadership: A Realist in Surreal Times

Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy

By Henry Kissinger

Penguin Random House/July 2022

Reviewed by Lisa Van Dusen

August 3, 2022

It says something about how the human brain sorts information that when I think of Henry Kissinger, I don’t think first of his role in America’s Vietnam policy or of the protracted, pre-Silicon Valley nerd stampede into politics propelled by his pronouncement from the front lines of peripatetic playboyism that power is an aphrodisiac. When I think of Henry Kissinger, I immediately think of the time, while I was living in Manhattan, that I saw him twice in one day — once on the Upper West Side and once on the Upper East Side. It was like that scene in The Thomas Crown Affair — not the classic Jewison version, the stylish McTiernan re-boot — when the Metropolitan Museum of Art is overrun by Magritte Bowler Hat Men, only in this case a Kissinger around every corner.

For more than half a century, Henry Kissinger has indeed been everywhere. From his early role as a consultant to the Kennedy White House to his recent — still lucid at 99 — controversial statements on Russia’s endgame in Ukraine, Kissinger has been a voice on foreign policy always audible above the din. That influence has been nurtured far beyond his most prominent official roles as Richard Nixon’s national security adviser and then secretary of state to both Nixon and Gerald Ford, through the cyclical publication of bestselling books on timely subjects from diplomacy to China to the societal implications of artificial intelligence.

Kissinger’s latest book, Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy, is both a little mistitled and a little less timely. As a collection of leadership portraits — of Nixon, of postwar German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, postwar French President Charles de Gaulle, transformational Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Singaporean statesman Lee Kuan Yew and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher — the book is less an exploration of the psychology of leadership than a chronology of policy choices, many of which involved the author. And because the choices chronicled were all made before the turn of the millennium, when geopolitics was dramatically altered by the diplomacy, security and intelligence-revolutionizing arrival of the internet, their value to readers may be more academic and nostalgic than practical.

But Leadership is full of the sort of anecdotal colour that only Kissinger, who was in so many rooms where it happened for so long, can still provide about events to which most other witnesses have long since departed. That value strikes the reader gradually, until it is punched home 50 pages in, when de Gaulle asks Kissinger in a pull-aside during Nixon’s first visit to the Élysée in 1969, “Why don’t you leave Vietnam?” to which Kissinger replies, “Because a sudden withdrawal would damage American international credibility.”

For critics of realism, the approach to international relations most closely identified with Kissinger, that quote — previously reported and dissected — may be the rhetorical Exhibit A in the case against his role in a war that saw a further 20,000 soldiers killed between the moment he uttered it and the fall of Saigon in 1975. As a schema for statecraft that places national interest above all other considerations, with national interest defined in sometimes brutal terms, realism permeates Kissinger’s choice architecture so thoroughly that it seems less like a strategic approach than a character trait.

Indeed, his realist reflexes may have enabled the apparent meeting of minds that defined his relationship with Nixon, to the extent that they overlapped with the president’s natural bloodlessness. If you recoil at the prospect of reading 80 pages of revisionist hagiography on Nixonian foreign policy, you’ll get over it in short order thanks to the surprisingly entertaining parade of euphemisms Kissinger marshals to re-cast Nixon’s fatal flaws as, if not strengths, navigable idiosyncrasies. “Nixon’s immediate entourage learned that sweeping statements were not necessarily intended to result in explicit actions,” Kissinger writes of the president’s men. In other words, he was a little crazy before he was a lot crazy. Eyes were rolled and accommodations were made. Or, as former Eisenhower aide Bryce Harlow quipped of Watergate, per the author’s citation: “Some damn fool got into the Oval Office and did what he was told.”

The author refers unironically to Nixon’s ‘creative leadership’, to his ‘imagination for tactical boldness’ and to the conspiracy that stands as a testament to those and other qualities as ‘the Watergate tragedy’, as though it was something that befell Nixon as opposed to a spectacular downfall of his own making.

Leadership is often more about Kissinger and his role in events than about the leadership qualities of the leaders in question — not unique to this book in the genre — and it sometimes shrinks Watergate to what seems to be, if you didn’t know better, a routine scandal. The author refers unironically to Nixon’s “creative leadership”, to his “imagination for tactical boldness” and to the conspiracy that stands as a testament to those and other qualities as “the Watergate tragedy”, as though it was something that befell Nixon as opposed to a spectacular downfall of his own making. That Kissinger continues to compartmentalize it, half a century later, beyond his judgment on Nixon’s status as a statesman does both the credulity of his readers and the credibility of his other judgments in this book a disservice.

It’s interesting to look back now at Kissinger’s cultural footprint during that tumultuous time. More than an éminence grise, he was a figure of pop-culture fascination as the rumoured Edgar Bergen behind Nixon long before Karl Rove made “Bush’s brain” a chyron ID. Kissinger has spent decades countering this trope, including in this book, by exhaustively portraying Nixon as his own man on foreign policy.

In 1972, in an interview with the formidable Oriana Fallaci that was so monumentally ill-advised it was the sole subject of an interview-about-the-interview that Fallaci later did with Dick Cavett, Kissinger famously fed the perception that Nixon was a supporting actor in his own ambition drama with this Alan Ladd-as-Shane evocation as to the source of his own mystique: “The main point arises from the fact that I’ve always acted alone. Americans like that immensely. Americans like the cowboy who leads the wagon train by riding ahead alone on his horse, the cowboy who rides all alone into the town, the village, with his horse and nothing else.” Nixon, reportedly, was furious. But not furious enough to dispel the myth by firing him.

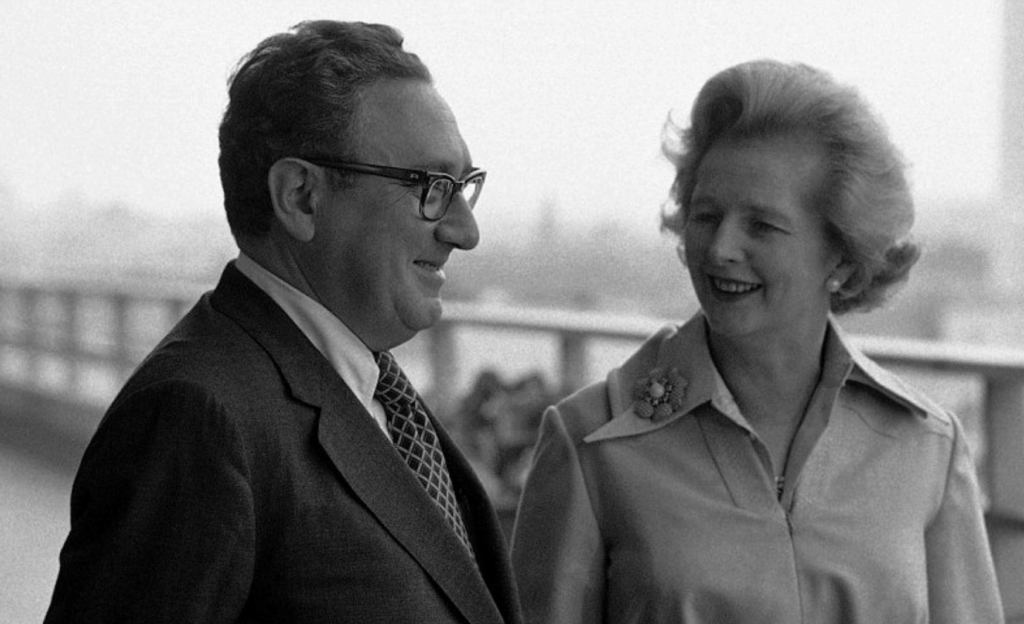

Henry Kissinger and Margaret Thatcher in Washington, 1975/AP

Henry Kissinger and Margaret Thatcher in Washington, 1975/AP

For critics of Realpolitik — the more Machiavellian branch of realism Kissinger has eschewed as a label and that liberals and idealists see as a sort of extreme intellectualization in theory and extreme means-to-an-endism in practice — the consistent abstractions of the consequences of power vis-à-vis any apparent consideration of how the lives of human beings are enhanced or destroyed in these choice chronologies does little to dispel that perception. The notable exception, interestingly, is Thatcher, who wept over the losses of UK servicemen during the Falklands War.

She also succumbed to Kissinger’s core argument on the future of Hong Kong over the course of late 1982, including during a key dinner at Number 10 that November while Kissinger, as a private citizen, was acting as back-channel between the Chinese and UK leadership. Thatcher was adamantly opposed to ceding Hong Kong based on plausible recourse to international law in protecting the financial centre’s democracy from the separate treaty obligation to revert the New Territories to Chinese rule by 1997. Kissinger argued that position had to be abandoned in the face of the — hyper-realist — warning that China could simply take the island by force. Over months of pressure, Thatcher reneged on her vow to never give up Hong Kong and in 1984 signed the Sino-British declaration, sealing Hong Kong’s fate.

Whether these six leaders fall into the cometh the hour, cometh the man category (Adenauer, de Gaulle) or the power-of-personality bucket (Nixon, Sadat, Lee, Thatcher) they tend to be assessed by the author based on the degree to which they were able to impose their singular will against great odds — not always, as history has repeatedly shown, the healthiest quality in a leader. Perhaps the most useful section of the book is its conclusion, in which Kissinger views the current state of the world, especially the under-explored role and impact of technology, through the lens of leadership. His views on China, Russia, Ukraine and other major files currently confounding leaders are well worth processing because — not in spite — of the predispositions and biases made clear in the previous 400 pages.

As leadership portraits go, Leadership in Turbulent Times by Doris Kearns Goodwin provides what is arguably a more complete study of leadership because it includes analysis of how the four presidents the author has profiled — Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson — related to their fellow citizens, to their moral obligations to those citizens and to America beyond its status as an instrument of power.

It may also be more relevant to our Manichean moment, bedeviled as it is by the cavalcade of unreal, irreal and surreal elements of so many of today’s power games. Which makes this either the worst or best time to be a realist, depending on your perspective.

Policy Magazine Associate Editor Lisa Van Dusen was a senior writer at Maclean’s, Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.