The COP26 Deal: President Sharma Rolls the Dice

Elizabeth May

November 13, 2021

Brinkmanship. I can think of no better word for the way UK COP26 President Alok Sharma played the endgame. Back in January 2020, Sharma was designated by Prime Minister Boris Johnson to run COP26 – in a year that stretched to two due to the COVID pandemic.

Earlier this week, when asked if he was going to play a high-stakes endgame, Sharma demurred, “I am known as ‘no drama Sharma’.”

Not quite.

I maintain that the success of these climate negotiations is very much determined by the character and skill set of the president. Stéphane Dion was uncommonly good at negotiating a successful COP11 at Montreal in 2005. Superb and heroic work was done by Mexico’s Patricia Espinosa at COP16 – rescuing the multilateral process after the train wreck of Copenhagen in 2009. And Copenhagen’s disaster was largely due (in my opinion) to the ham-fisted insensitivity to United Nations consensus-based process from Denmark’s then prime minister, Lars Rasmussen.

I am certain that had the negotiations in 2009 not been held in Copenhagen with that woeful presidency and instead had taken place in Paris with the inspirational leadership of former French prime minister Laurent Fabius, we could have had the success of Paris back at COP15 in 2009 and not have had to wait until 2015.

In Glasgow, Sharma departed from the tradition of successful presidents in being more like Rasmussen than Espinosa, Dion and Fabius. He led negotiations in ways that prompted complaints that the process was not sufficiently inclusive or transparent. He also stopped the normal practice of keeping negotiations continuing through the night — consensus by exhaustion — and sent negotiators off to have a good night’s sleep. At 8 am Saturday morning, the UNFCCC website had a new, longer and in many ways stronger text for the overarching decision of this meeting, called the Cover Decision.

The strong elements, the ones that may keep 1.5 degrees alive, are in the language of urgency, placing in the document the 2018 advice of the IPCC that to hold to 1.5 degrees steep cuts in GHG are required immediately. No one can claim that our goals from Paris are met by “net zero by 2050” when it is so clear that this is the decisive decade. The calls for urgent action for every nation to do more to improve their plans and targets are couched in language of deep concern and alarm. The mention of fossil fuels, even watered down, is an essential step.

As well, for the first time, the COP decision brings in the key role of “nature-based solutions” and the protection of biodiversity. While disappointed by the failure of wealthy nations to meet their decades-old commitment to climate finance, issues of adaptation, loss and damage and other aspects of financial support to developing nations made significant progress. At least enough for a package of measures that saved Glasgow and COP26 from flaming failure.

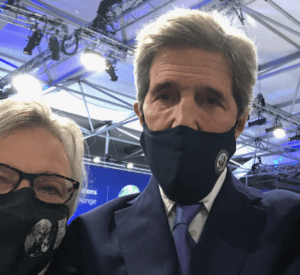

In terms of atmospherics, Sharma allowed a lot of milling about before starting the session. In fact, the room was a sea of people visiting, chatting, and sometimes in intense negotiation. I ran into US climate envoy John Kerry as I was making my way through the rows of chairs. Whether he really remembered me from Paris, hard to say of a skilled politician, but Kerry was ever so kind. He was very pleased that, as a Canadian MP, I expressed gratitude for the cancellation of the Keystone pipeline. My friend Lisa de Marco, climate lawyer and expert from Toronto, stepped up with her camera and there we were in selfie mode.

When we finally were called to order, for hours through Saturday afternoon, delegation after delegation expressed willingness to accept the package of decisions. Low-lying island states and developing countries, the EU and USA, expressed their willingness to accept an imperfect agreement.

The calls for urgent action for every nation to do more to improve their plans and targets are couched in language of deep concern and alarm. The mention of fossil fuels, even watered down, is an essential step.

As my friend James Shaw, minister of climate from New Zealand, also the co-leader of New Zealand Greens, put it, this set of agreements constitutes “the least-worst outcome … Is it enough to hold temperatures to 1.5C? I don’t think I can say it does.” But, he continued, it is preferable to accept this package now and get to work. The alternative, more talking and delay, was just unacceptable.

As the “disappointed but prepared to accept this package” statements continued, we were brought up short by India injecting that it could not accept paragraph 36, demanding that the language on phasing out coal power be removed.

China — which produced 50 percent of world’s coal power in 2020 as opposed to India’s eight percent — agreed, but less vehemently, ultimately joined by Venezuela, Iran, Nigeria, and South Africa.

For the rest of the afternoon, in polite diplomatic terms, delegations pleaded with India to compromise. Many spoke of their own children and that they were not prepared to go home and tell their own children they had failed in Glasgow. The minister from Tuvalu held up a photo of his three grandchildren for the whole time he spoke.

After hours of what was called an “informal stock-taking”, Sharma gaveled us to adjournment and said the final plenary would begin soon. This was not what I expected.

There was a huge gap and starting a final plenary seemed unwise. But, as ever, the huddles in the room continued. John Kerry of the US, with European Commission’s Vice President Frans Timmermans, over to Xie Zhenhua, China’s head of delegation. Sharma with his team in a huddle. Negotiators in small groupings, while incongruously, other groups of delegates who had worked on negotiating aspects of the agreements came forward for group photos at the front of the room. It began to feel like a high school graduation. The mood shifted from tense to ebullient.

It seemed a deal was being hatched. It certainly was the case that the deal-making was not the ideal approach of the United Nations multilateral process. As we reconvened for the final plenary, never having left the room, China and India asked for the floor to broach their compromise. They would accept the “phase-down” of coal, not the phase-out. While the logjam was broken, the nations that understand we have to keep the hope of holding to 1.5 alive complained bitterly. Switzerland, Marshall Islands and Fiji among many others complained about the non-transparent process and the setback in moving against coal.

Sharma then apologized for the way the process had unfolded. He appeared to express a genuine regret for his methods. And then he broke down – just a bit — in tears. Even as I joined in a standing ovation, I wondered if we were being played. He then gavelled through the key decision to cheers.

So much for “no drama Sharma,” but there is a deal.

And so, we leave Glasgow. It was not a great success, but it did not fail. We made progress, but we needed to do far more. The clock is ticking toward irreversible, unstoppable climate catastrophe. I have my parliamentary priorities clear. Canada must do more and move from the back of the pack to climate hero.

Contributing Writer Elizabeth May, MP for Saanich-Gulf Islands and former Leader of the Green Party of Canada, has been filing frequently for Policy Magazine from COP26 in Glasgow.