Lucky Jim: From ‘Gutsy Little Guy’ to the Senate of Canada

Two years after retiring from the Senate, Jim Munson reflects on his nearly half-century journey from scrappy reporter to prime ministerial advisor to activist Senator.

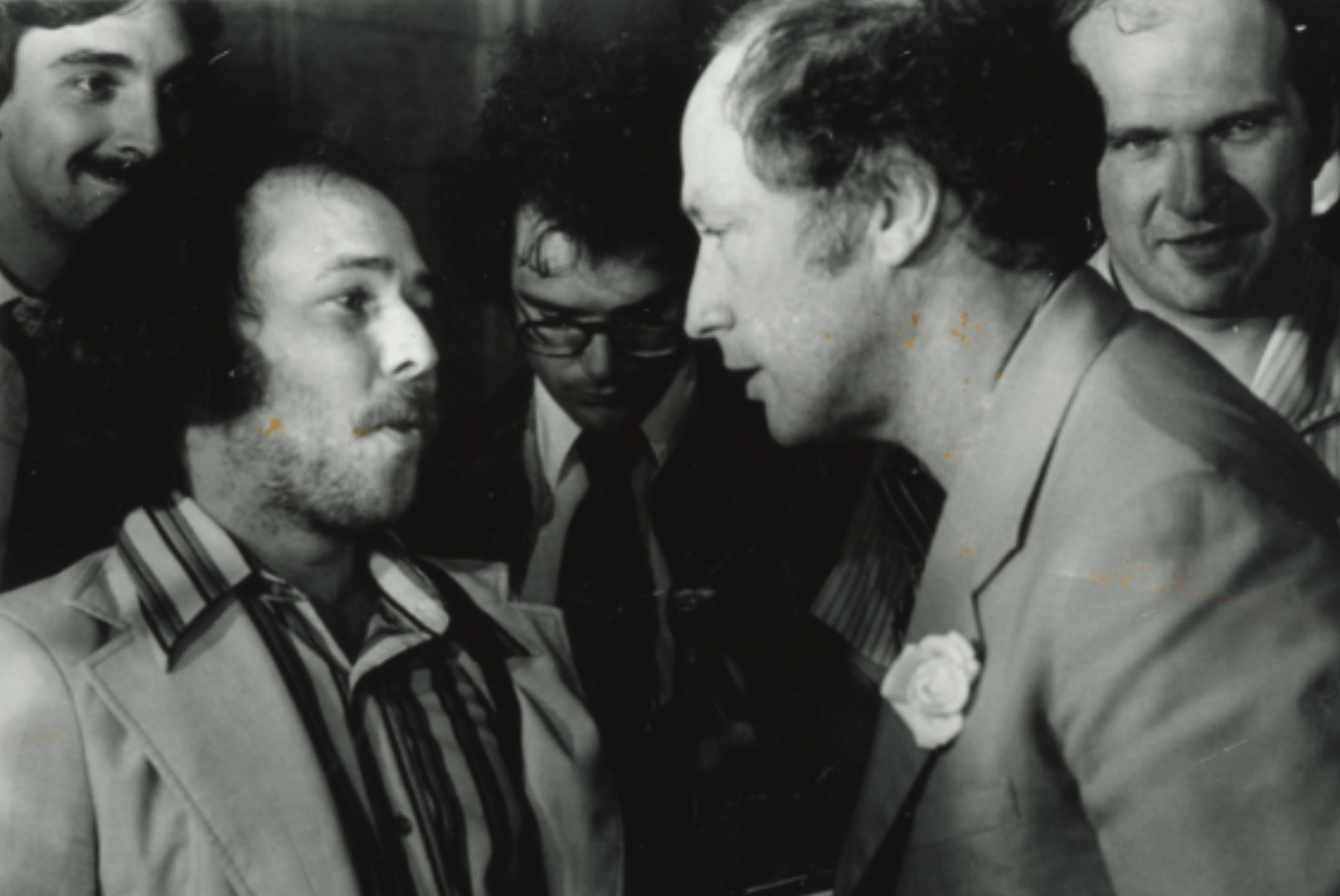

You started it: Jim Munson vs. Pierre Trudeau/Courtesy Jim Munson

You started it: Jim Munson vs. Pierre Trudeau/Courtesy Jim Munson

By Jim Munson

October 22, 2023

“I am never going over to the dark side,’’ declared a fellow journalist walking beside me along Ottawa’s Wellington Street, across from Parliament Hill. It was 1975, and for the uninitiated, “the dark side” was ironic shorthand for the murky world across the great divide between the media and the politicians they cover.

Was the vow inspired by a cold-sweat workplace nightmare? Another hangover from yet another raucous night at the National Press Club? An argument with an overly protective press aide? Perhaps all those things and more.

At 29, I was newly arrived on the beat, determined to infiltrate the obscure world of politics and shake things up on the Hill. There were stories to uncover in that dark side of the world, and there was nothing like being fuelled by a competitive spirit. I knew it all, or at least I thought I did. As a radio reporter, I wasn’t really interested in deep explorations of public policy. I was more interested in getting a sound bite to complement the story of the day. If I needed anybody to add context to a story, I could always find a knowledgeable expert or professor.

In the “hot room”, or smoke-filled third floor Centre Block press room, you could always find collaborators who stalked the same corridors looking to turn the political page upside down — after all we were covering the dark side, and bringing it to light by catching out politicians was a daily mission.

But in that tap-tap world of typewriters, watching the icons of journalism compete for a headline story, I also lived in awe and wonder. Was I really covering the dark side? Sitting in the House of Commons were politicians who were not playing for television and the nightly newscasts. There were no cameras in those days, which made for genuine political theatre as opposed to the performative kind. I couldn’t wait for question period to start. The galleries were full, both public and press. Down below, the real competition was about to begin. If you love politics and if you love people, then this was the arena where the great Canadian drama played out — the cut and thrust of rhetorical gamesmanship, the settling of political scores, the making and breaking of careers that went along with conducting the people’s business amid constant scrutiny. Characters like Lincoln Alexander, Ed Broadbent and Pierre Trudeau dominated the debate in those days.

I carved out a place for myself in the daily dance between the politicians and the press, less a Fred Astaire than a Tommy Burns — the only Canadian-born world heavyweight boxing champion in history, and, at 5’7’’, the shortest. I was fast, relentless and pugnacious — a kid from the Maritimes on a mission to ask the questions real Canadians would ask if only they could, and never taking “no comment” for an answer.

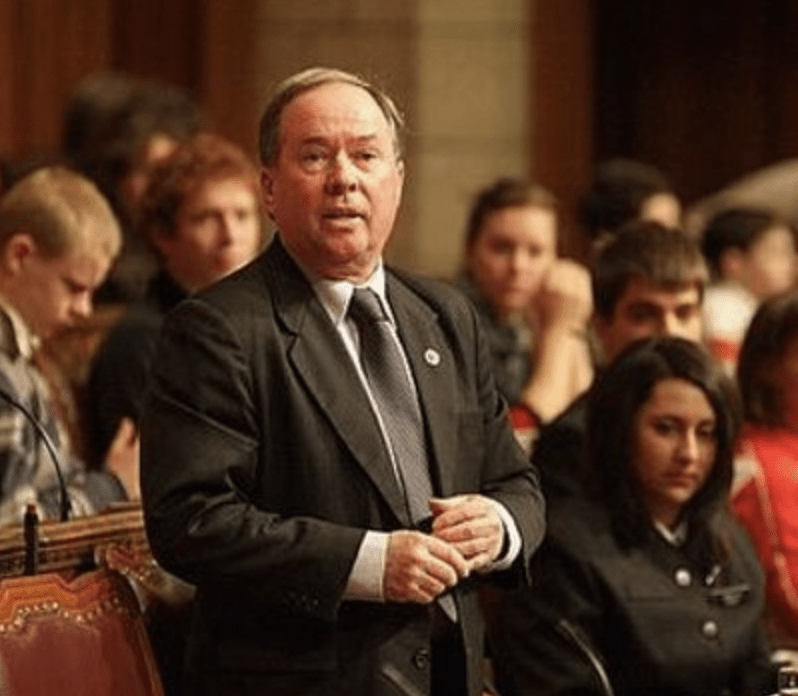

In the Red Chamber on National Child Day/Senate of Canada

Decades later, in 2016, sitting in my Senate seat in the ornate Red Chamber, I was asked discreetly by a fellow Senator: “Did you really get into a fistfight with Pierre Trudeau?” “Well,” I said, “It was more of a shoving match, but he pushed me first.” I can still see the shock on the face of that senator. Forty years had passed since the day in the summer of 1976 when the Prime Minister walked out of a cabinet meeting seeming flustered. The Olympic games were about to be held in Montreal and African nations were threatening to boycott over New Zealand’s sporting links to apartheid South Africa. I asked Trudeau what he was going to do about it. His answer: “Don’t push me”, as he proceeded to push me away. Instinct being what it is, I pushed back. A shoving match ensued.

Today, if my reporter son got into that sort of fracas with Trudeau’s prime-minister son (which would never happen because my son, James, is much less combative than I was and Justin, being an actual boxer, would likely knock him out regardless) he’d be tackled by the RCMP, and they would not care who started it. But this was 1976, and I think Mr. Trudeau had a soft spot for me. After all, in Richard Gwyn’s book, The Northern Magus, he called me “a gutsy little guy.” Indeed, it was a letter from Pierre Elliot Trudeau to my employer that saved my … job. In it, he said I was just doing my work, just like he was trying to do his work.

I am fully aware that when we reflect on this incident, it may seem an implausible leap to my subsequent two careers as a director of communications for another prime minister and as a senator. The word gratitude comes to mind as I try to unravel with these words a journey that was never planned.

First, let’s go back. At 19 and being away from home for the first time, I found myself, in 1965, working as a disc jockey in a 250-watt radio station in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. The year was 1965. I also read the news and did the occasional interview when a VIP came to town.

In 1966, former Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker flew in to support a byelection candidate by the name of John O. Bower. I was chosen to do the interview. Outside the station, the travelling parliamentary scribes were waiting in the fog in their trench coats, obligatory cigarettes damped by the drizzle. I welcomed Mr. Diefenbaker to Yarmouth, and 30 minutes later I thanked him. I did not ask one question in-between, but I did know one thing; I wanted to be like one of those trench coated parliamentary reporters. Though I eventually achieved that goal, I never could find a trench coat that fit.

In his new book, Paper Trails, Roy Macgregor refers to “Macgregor luck” in describing his journey from a small town to the larger world of newspaper reporting. I shared a similar journey but from another town, and to the world of television reporting, propelled by “Munson luck”.

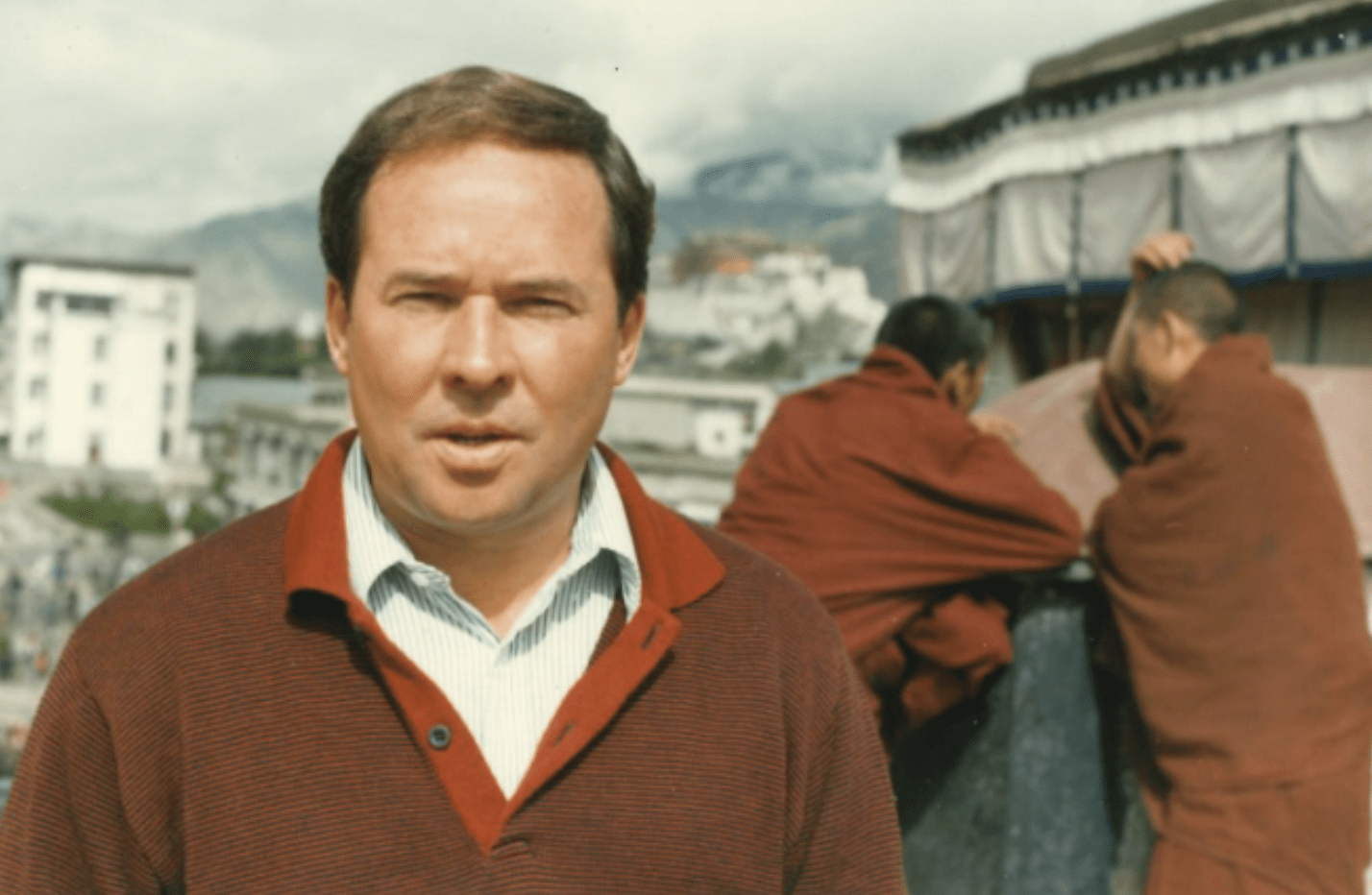

Reporting from Tibet while posted to China/Courtesy Jim Munson

Reporting from Tibet while posted to China/Courtesy Jim Munson

Along the way, there was coverage of the FLQ crisis, multiple federal elections, the US invasion of Grenada, the Iran-Iraq War, bloodshed in the Middle East and Northern Ireland, China and Tiananmen Square, and many stops in between.

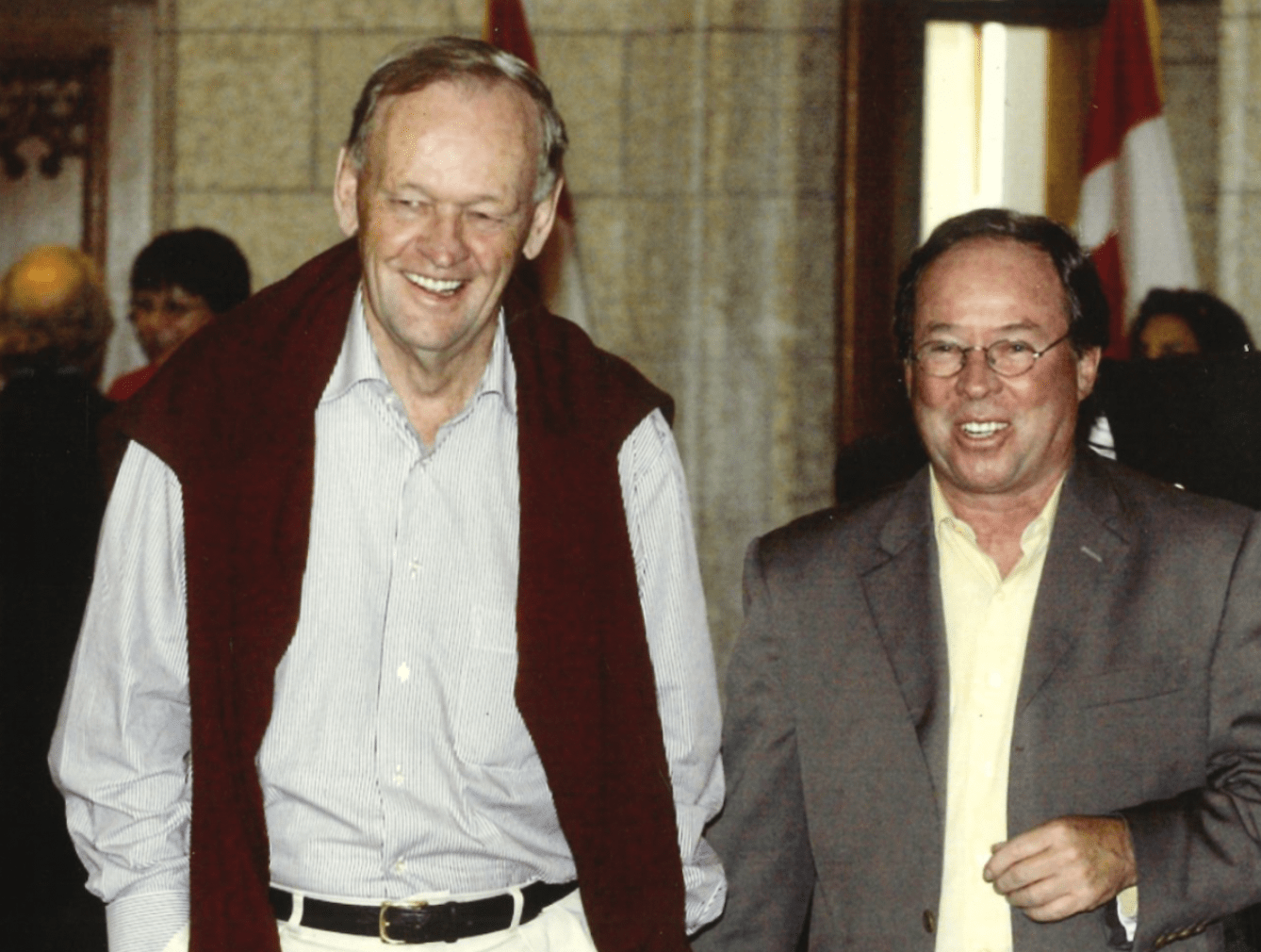

That life came to a crashing end in 2001. I was back on the Hill, after many years overseas and I was still living the dream. There was a shake-up at CTV, and I suddenly found myself, at 55, no longer on Parliament Hill. I was out of a job, and I was in tears. One day, as I was weighing offers to migrate to the dark side as a political advisor, there was a call from the Prime Minister’s Office. A voice any Canadian would recognize and most would’ve taken for a radio prankster, that of Jean Chretien, was offering me a job. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I thought about it for a day. It was the wise counsel of my wife, Ginette, who tipped the choice, reminding me that I was out of work and exhorting me to get over the whole “dark side” thing. Besides, I liked Jean Chretien. If any prime minister could relate to my “gutsy little guy” reputation and history of prime ministerial shoving matches, it was Jean Chrétien.

I don’t know how many of you have worked for a favourite uncle but during my time in the PMO, that is the way it felt working for Jean Chretien. There are so many stories to tell. But there is one that will stay with me forever. On the Hill, Mr. Chretien is known as “The Boss” and there are obvious reasons for that, but as prime minister, he never hesitated in asking for the views of the people he’d hired. We all know the story of Canada not going to war in Iraq. Prime Minister Chrétien was firm with George W. Bush: If you can’t show the weapons of mass destruction and if the war is not sanctioned by the United Nations, then Canada is not going to war. I recognized that there were more senior policy people with more informed views who advised the Prime Minister, but when he asked for my opinion, I simply answered, “What legacy do you want to leave your grandchildren?”

With Prime Minister Jean Chrétien/Courtesy Jim Munson

With Prime Minister Jean Chrétien/Courtesy Jim Munson

To be in the room with the Prime Minister when the decision was made not to go to war is a moment I will never forget.

What I discovered while embedded in the “dark side” of the Prime Minister’s Office and Privy Council Office was a bunch of very hard-working people committed to improving the lives of their fellow Canadians. I know that some people — especially my former colleagues in the media — said at the time, that I’d “drunk the Kool Aid” but I’m stating the observation above as a journalist. My outsider’s cynicism about how political power works on the inside was overtaken by the facts, and public service was the dominant story.

Knowing this wasn’t going to last forever, I had to start thinking what was going to happen beyond the Chretien years. All I’d ever wanted to be was a reporter, asking questions, always curious, with the bonus of having your employer pay your way to see the country and the world. But what now?

“Jimmy, why don’t you sit beside me for breakfast,” said The Boss as we were departing Ottawa for Abuja, the capital of Nigeria, on Jean Chretien’s last big foreign trip. There would be only a few weeks to go before he would leave 24 Sussex. I didn’t usually sit beside by the PM on flights. Somewhere over the Atlantic Ocean, he leaned over and said: “What would you say if I made you a senator?” This time, I didn’t hesitate; the answer was an emphatic “Yes”. While I was concerned about what my journalist friends would think, for the most part, they were kind and I was relieved.

During the Autism Awareness Summit with fellow senators/Courtesy Jim Munson

In writing this piece of personal history, I have reflected on my subsequent 18 years in the Senate. I think of a son with Down Syndrome who died so long ago, I picture the children I saw in refugee camps who would never be adopted because of a disability, and I think of the opportunity that knocked on my door. It has been a long and winding road to the world of public policy but as a senator, I could do something about the things I really cared about instead of observing from the sidelines. I could use the institution to fight for the rights of those with intellectual disabilities. I hope I did that. As with my previous misconceptions about the “dark side” of politics that were blown away by my time on the inside, I discovered that the Senate of Canada – unlike what you may have heard — is populated by people who work incredibly hard to make sure that complex policy issues receive the scrutiny they deserve, and that problems are solved in the best interests of Canadians.

I may be beyond The Hill, but I am not over the hill. In this fight for a world of inclusion I continue to advocate for a National Autism Strategy. We are going to get there.

Looking back at the past 50 years, I remember a day in the 70s, sitting beside Ottawa’s Rideau Canal and reading a book by Gratton O’Leary, the legendary Ottawa Journal editor and Senator. It was called Recollections of People, Press and Politics. Our paths never crossed, but I was fascinated by his stories. History teaches us so much. Was that the fire that lit this journey? I’m not sure, but curiosity has always led me to ask: “What’s down that road?”

You never know until you take it.

Jim Munson spent two decades as a political reporter and foreign correspondent for CTV News before being named Prime Minister Jean Chrétien’s director of communications. He retired from the Senate of Canada in 2021, after 18 years of service, including as a passionate advocate for autism research and awareness.

You can donate to help early intervention for autism at quickstartautism.ca.

For further information about autism awareness, including about the Jim and Ginette Munson Autism Leadership Award, please visit the Autism Alliance of Canada.