Macron vs. Le Pen: More Reality vs. Inauthenticity than Anger vs. Fear

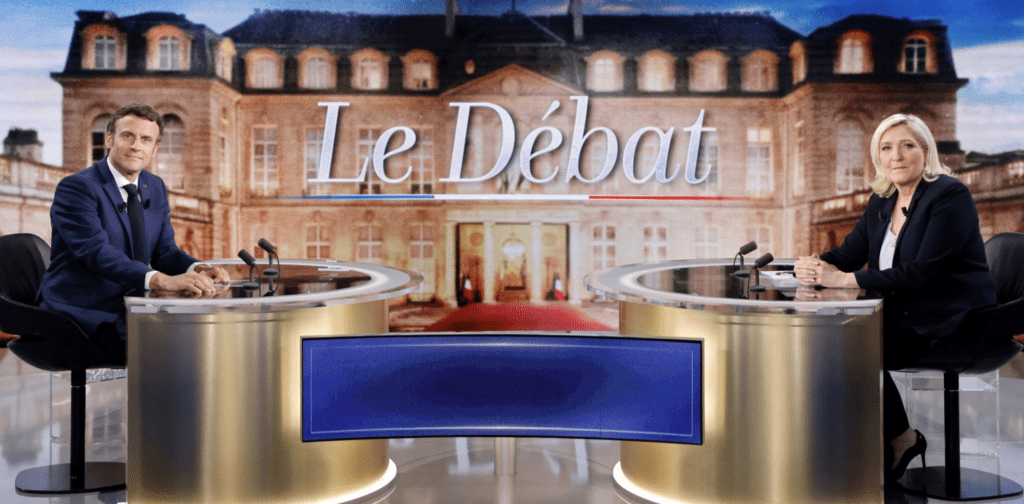

French President Emmanuel Macron and far-right candidate Marine Le Pen on the set of their debate/France24

French President Emmanuel Macron and far-right candidate Marine Le Pen on the set of their debate/France24

Lisa Van Dusen

April 20, 2022

As Volodymyr Zelenskyi has pointed out repeatedly since his country was unlawfully invaded; in a global war on democracy —with apologies to the late Tip O’Neill — no politics is local.

It’s a fact of the borderless, brackish confluence of 21st-century geopolitics and politics that French voters may do well to remember as they ponder the possible outcomes of the deuxième tour of their présidentielle on April 24th.

In this run-off election, they’re choosing between the incumbent centrist, Emmanuel Macron, whose greatest drag is his incumbency in a country known to turn like vin vinaigré on its sitting presidents, and Front National scioness Marine Le Pen, rhetorically tranquilized and optically repackaged for more plausible electability.

Their one televised debate — a rematch of the 2017 tête-à-tête in which Macron famously wiped the floor with Le Pen — was held Wednesday evening as the first close campaign encounter in a contest French commentator Dominique Moïsi recently framed as anger vs. fear. It turned out to be more reality vs. inauthenticity.

Macron fought this year’s kinda kinder, sorta gentler, still fascist-adjacent Le Pen by swatting away her dubious promises and empty denials like a very knowledgeable, fairly appalled Jesuit. The highlight was Macron’s calling-out of Le Pen’s $12 million USD loan from a Russian bank to her party and her support for Vladimir Putin as a presidentially disqualifying (not in so many words) conflict of interest. “Quand vous parlez à la Russie, vous ne parlez pas à un autre dirigeant, vous parlez à votre banquier!”, he said; “When you talk to Russia, you’re not talking to another leader, you’re talking to your banker!” Her response, that she had to get a loan from a Russian bank because no French bank would lend to her, did not inspire confidence. Macron also warned that Le Pen’s plan to ban Muslim headscarves in public places would trigger “civil war”; certainly, her plan to hold a referendum on immigration would make Brexit look unifying.

If Le Pen’s metamorphosis is any indication of history-sanitizing electability makeovers to come, stay tuned for a cardigan-sporting, puppy-snuggling, Wordle-playing Donald Trump sometime between now and 2023.

Le Pen, daughter of twice-convicted Holocaust denier Jean-Marie Le Pen, has spent the last decade — through two failed presidential bids — in an explicitly branded dé-démonisation project designed to scour away her more persistently unelectable qualities with humanizing Instagram images of her cuddling kittens and walking barefoot on the beach. The Front National party her father made notorious was rebranded the Rassemblement national in 2018. If Le Pen’s metamorphosis is any indication of history-sanitizing electability makeovers to come, stay tuned for a cardigan-sporting, puppy-snuggling, Wordle-playing Donald Trump sometime between now and 2023.

One of the sign-of-the times curiosities of this French campaign has been the way in which Le Pen’s efforts to trade her father’s embrace of powerlessness as the price of fascism for a more mercenary approach to democracy has been portrayed like any other element of her candidacy — as though her electability should be enhanced by her relentlessness in misrepresenting it.

In a global propaganda context in which populism is used as a sort of fig leaf for a breed of political asset willing to do anything to undermine democracy in exchange for power (Trump, Duterte, Bolsonaro…), the labelling of Le Pen as “populist” is telling. For a potential change agent willing to rationalize all the same anti-democracy agenda items Trump and other weaponized leaders have — the weakening of the EU, the weakening of NATO, the closing of borders to immigrants and refugees, an emphasis on the soft paternalism of incipient authoritarianism rather than human rights…for starters — populist is a more marketable label than some of the more accurate ones.

In the last poll before a debate that Macron clearly won Wednesday (or, as one France24 commentator put it, if it hadn’t been for the floor-wiping precedent of 2017, we’d have said he just wiped the floor with her), the spread in his favour was at 13 points. The cliché of French elections is that, in the first round, people vote with their hearts and in the second with their heads. Perhaps this time, they’ll do both.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine. She was a senior writer at Maclean’s, Washington/international affairs columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.