March Brakes

By Douglas Porter

March 15, 2024

Long-term interest rates shot higher this week, driven by yet another hotter-than-expected set of readings on U.S. CPI and PPI, as well as heavy hints that the Bank of Japan is preparing to move away from both negative rates and yield curve control. This late-winter flurry reached land just ahead of next week’s FOMC and BoJ meetings, aggravating the sell-off. Ten-year Treasuries vaulted more than 20 bps to above 4.3%, while the shorter end was savaged even further as expectations of Fed rate cuts get dialed back. The rumeur du jour was that the Fed could scale back its dot plot to just two cuts for 2024 at next week’s meeting.

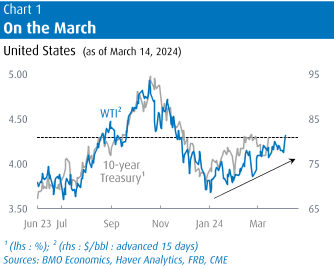

Not helping matters in a sagging bond market was the ongoing comeback in oil prices, which hit their highest level since late October at $81/bbl—and crude has been a quiet leading indicator for yields over the past year (Chart 1). We had assumed an $80 oil price in our forecast for this year, so this year’s back-up does not meaningfully change our inflation or growth calls just yet. The risk, though, is that the rise in crude is only just the beginning, and energy is an ever-present threat to upsetting the cozy consensus that inflation will continue to simmer back down to around 2%. Note that energy prices have dropped 1.7% y/y in the CPI, while food from home costs have ebbed to just 1.0%. Together, that’s played a big role cutting inflation down to size (3.2% overall).

It would thus be a problem, even if just for expectations, if oil and/or food sparked again, given that core inflation is stubborn at 3.8%. As it stands, U.S. inflation expectations are holding reasonably steady at right around the 3% mark on both a 1- and 5-year horizon, as per the University of Michigan survey. That’s both a) a fairly reasonable call on the inflation outlook, but b) about half a point higher than the pre-pandemic norm. So, while inflation expectations have calmed to much more reasonable levels, we are still well away from normal, and sensitive to a quick back-up should energy prices flare anew.

Equity markets were not particularly rattled by the sour inflation news nor the upward lurch in bond yields. Notably, the MSCI World Index hit a record high on Tuesday, the very day of the meaty CPI result. Still, the PPI piled on, and the prospect of BoJ tightening weighed as the week wore on, leaving stocks struggling to stay flat on balance. One emerging train of thought has been that the equity rally doesn’t really require Fed rate cuts, since earnings are thriving again amid a firmer-than-expected U.S. economy.

That brave talk quieted down as the market further scaled back rate cut expectations—after next week’s presumed no move, the May meeting is now also largely seen as a “no hoper” for the first cut, and now even June is viewed as a close call. We continue to like our call of cuts starting in July, which the market is gradually gravitating to as well. What we like less is our call of 100 bps of cuts through the second half of the year. The persistent strength in the U.S. economy—we upgraded our Q2 GDP call this week—sticky core inflation, and loose financial conditions all suggest that the risk for rate cuts is squarely on the side of less, not more for ‘24.

Canadian yields also forged higher this week, and, for a change, the upswing was almost in lockstep with the Treasury sell-off. The all-important five-year bond was especially hit hard, pulling yields up almost 25 bps in a week to above 3.6%, or almost 50 bps higher than where they ended 2023. While Canada’s CPI report is not until next Tuesday, the sell-off was in sympathy with the U.S. disappointment and likely also reflected the view that the domestic result may be ugly. We are pencilling in a meaty 0.6% m/m rise for February, which would push headline inflation back up above 3%—it’s never easy, is it?

In fact, our whisper number is even higher, but the stunning downside surprise in last month’s inflation report has left us on the cautious side. The underlying figure will not be nearly as atrocious as our headline call, since there is roughly 0.3 ppts of seasonality loaded in the figure (i.e., February is normally a month of large price increases). For some mysterious reason, Canadian markets and analysts insist on focusing on and reporting the raw, unadjusted CPI figures each month, even though a seasonally adjusted figure is readily available. Trust me, we have tried to change the conversation many times over the years, to little avail. Even with that quibble, we are expecting the annual trend in the key core measures to also back up to around 3.5%. Our focus will be especially intense on the Median measure, as Governor Macklem appears to be particularly fond of this metric.

The expected back-up in Canada’s headline and core CPI will be a bit of a communications challenge for the Bank. This will be the last CPI until the next rate decision on April 10. On the one side, it will pretty much be Exhibit A as to the Bank’s message of patience on the rate cut front. However, on the other side, it will be tough for the Bank to offer up the chance of possible cuts at the meeting following in June—which just so happens to be the meeting we and many others had anticipated the initial rate cut. However, by June the Bank will have two additional (and possibly more friendly) CPI results in hand, as well as the specifics of the federal budget (which is expected to mostly hold the line on new spending). If underlying inflation truly is moderating to more comfortable levels, amid a soft domestic economic backdrop, it should be reasonably apparent by June.

One slight wrinkle for monetary policy from the fiscal front is that the provinces are almost uniformly marching to a different beat. We noted last week that the provincial budgets on offer so far in 2024 have all seen rising spending, bigger deficits, more borrowing. Quebec’s effort this week kept right on that theme, projecting the largest budget deficit on record in nominal terms ($8.8 billion on a public accounts basis), and the largest as a share of GDP since the mid-1990s (at 1.5%). The combined provincial deficit is now tracking an increase of roughly $10 billion from last year, with heavyweight Ontario yet to weigh in (due March 26). That’s 0.3% of GDP, some of which is due to higher interest charges and some of which is cyclical, so it doesn’t represent a huge net new stimulus. Still, at the margin, it is mildly working against the monetary tightening skew, making it slightly more difficult for the Bank to trim rates. Again, it’s never easy, is it?

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.