March-ing to a Different Drummer

By Douglas Porter

March 01, 2024

Taking a step back from the trees to look at the forest, the major message from the recent round of economic data globally is that growth is still chugging along while inflation continues to walk down a jagged path toward normalcy. And, together, that’s a good thing. At least to this point, it appears that the massive rate hikes of the past two years have struck just the right balance by chilling growth enough to undercut the most extreme inflation pressures, without tipping the economy into an outright downturn. Of course, even mentioning this has the feel of discussing a no-hitter with the pitcher in, say, the seventh inning—that is, just before the job is finished, with the risk of jinxing it all. Markets have no fear of jinxes, and are eagerly pricing in a soft landing with the MSCI World Index hitting new highs this week and up almost 20% y/y.

In the U.S., some may quibble that the meaty 0.4% rise in the core PCE deflator in January hardly seems like inflation progress. But the bigger picture is that the annual trend has moderated to its slowest pace since March 2021 at 2.8%—half the peak two years earlier—and the six-month trend is an acceptable 2.5%. Friendly base effects suggest that the yearly pace could easily take a few more steps down over the next three months. Other core metrics are a bit higher, but also moderated in January, to 3.2% for the Dallas Fed’s trimmed mean, and 3.5% for the Cleveland Fed’s median PCE. These measures are broadly comparable to the Bank of Canada’s core metrics, and send the message that there is a bit more work to do.

The biggest risk to the soft landing scenario in the U.S. appears to be that there will be no landing at all, with voices growing that rate cuts may be even further delayed (perhaps beyond our call of a July start). This week’s slate of figures was mixed, with a generally softer tinge, but not indicative of an economy rolling over. Probably the most important release sagged in February, with the ISM factory index dropping 1.3 points to 47.8, but almost right back at year-ago levels. Consumer sentiment also fell more than expected last month, while real spending, pending home sales, and core durable orders all dropped in January. Next week’s jobs report is expected to show payroll gains cooling to 190,000 after the fiery prints in the two prior months. Together, these results helped clip Treasury yields, and leave us comfortable calling for GDP growth to ease to 2% a.r. in Q1 from 3.2% in Q4.

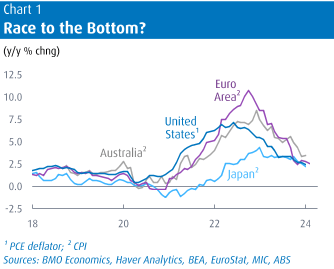

A wide variety of other major economies also reported a gradual descent in inflation trends, even as growth stayed on course. The Euro Area, often first out of the gate on monthly CPI, reported headline inflation eased two ticks to 2.6% y/y in February, and to 3.1% for core. While both were a bit above consensus, note the very ‘normal’ feel to those figures, as opposed to the grotesque 5, 6, or even 10% readings from 2022. Similarly, Japan’s headline inflation has been cut in half to 2.2%, from the four-decade peak of 4.3% in 2022. And while Australia’s progress stalled at 3.4% on inflation, that’s still down 5 ppts from the peak of late 2022 (Chart 1).

Meantime, on the growth front, most of the major overseas economies saw their PMIs holding just below the 50 line in February (and a bit above for China). The eye-popping number this week was India’s rollicking 8.4% y/y rise in Q4 real GDP, which lifted full-year growth to 7.7%. With a 7% weight in the global economy, the boom in India is a big reason the world is still churning out sturdy 3% growth rates. Still-healthy global growth will likely frustrate faster progress on inflation, and this week’s back-up in oil prices to above $80/bbl is a red flag.

Solid external conditions were a key factor steering the Canadian economy away from technical recession waters in Q4. Led by a pop in exports, GDP managed to grow at a 1.0% annual rate, consistent with the full-year advance of 1.1%. While dismal in per capita terms, the modest headline growth is still much better than we and the consensus had anticipated a year ago. And that’s despite a variety of special factors—including drought, fires, and strikes—shaving at least a few ticks from growth. Because of a decent start to 2024, with January GDP expected to pop 0.4%, we nudged up our full-year estimate of growth to 1.0%. That meagre growth is weak enough to further chip away at inflation, although note that Canada’s PCE deflator (not a widely followed measure) eased only slightly in Q4 to 3.3% y/y. Still, it’s down almost 3 ppts from the 2022 peak, and that’s without a recession—albeit barely. The modest growth and only gradual inflation progress are expected to keep the Bank of Canada on ice next week, and still sounding cautious.

The passing of Brian Mulroney, Prime Minister of Canada from 1984 to 1993, conjures up many memories from a relatively tumultuous period for the country. There is no debate that he left a very important economic legacy, with his two most memorable achievements being Canada-US free trade (the FTA) and the GST. On the former, Mulroney was unquestionably the driving force behind what would become NAFTA and ultimately the USMCA/CUSMA, by sparking the initial free-trade talks with the U.S. in the mid 1980s. Those too young to recall may not realize that the 1988 federal election boiled down to a referendum on the FTA. (Suffice it to say, the FTA was much less of a factor in the U.S. elections just two weeks earlier that year!) The polls went back and forth on the merits of the agreement that fall, before the PCs won another majority victory, securing the deal.

Let’s just say that the GST, which arrived in 1991, is somewhat less fondly recalled by many. The sales tax now generates almost $50 billion per year (or $10 billion per point), or about 11% of Ottawa’s revenues. While unloved, it replaced the highly inefficient (and hidden) manufacturers sales tax, and was a significant positive step in improving Canada’s competitiveness. Switching to a GST had long been a goal in Ottawa, pre-dating Mulroney, but he was the PM who had the gumption to push it over the finish line. While wildly unpopular, and one of the three main reasons the PCs were subsequently annihilated in the 1993 election, it was the right thing to do.

On a personal note, I only had one opportunity to meet Mr. Mulroney, and it was about 20 years after he left office. I was coming into a TV studio to do an interview on, coincidentally, the 25th anniversary of the FTA, and he had just finished an interview, and we had a good chat on the deal and its effects. Whatever one’s political persuasion, his personal presence was awesome, he oozed charisma, and the main takeaway was his graciousness.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.