Master of the Game: Henry Kissinger and ‘Balanced Dissatisfaction’ Nostalgia

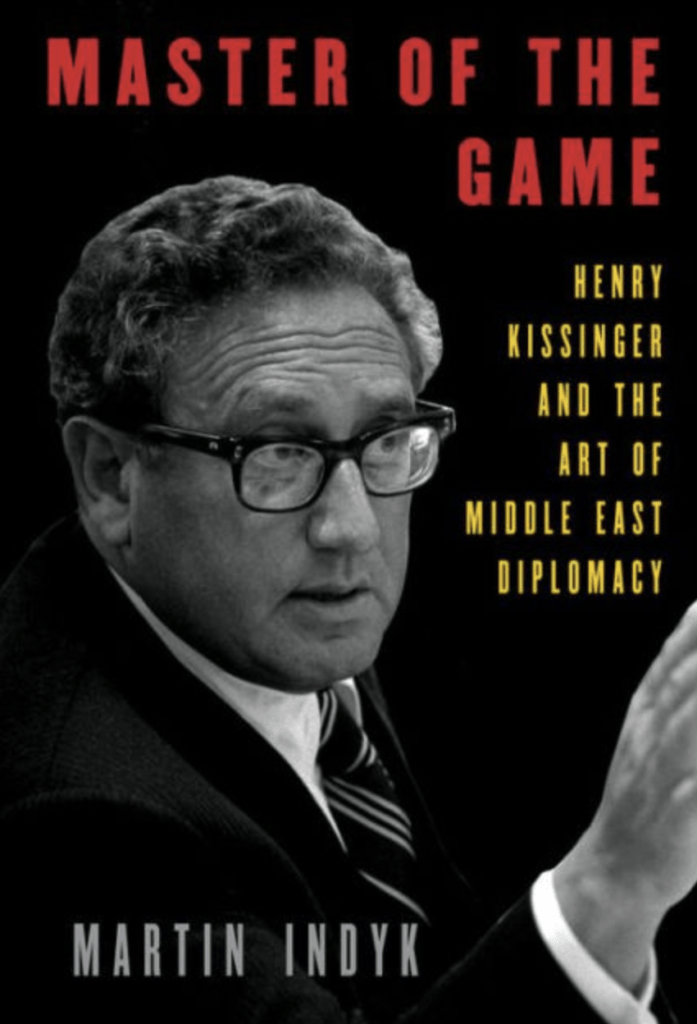

Master of the Game: Henry Kissinger and the Art of Middle East Diplomacy

By Martin Indyk

Penguin Random House/October 2021

Reviewed by Peter M. Boehm

March 22, 2022

The other day, as I was witnessing with the rest of the world the current Russian aggression in Ukraine, I wondered what Henry Kissinger would have in the way of strategic assessments and possible solutions. I wasn’t disappointed: the former US secretary of state and national security advisor, now in his 99th year, penned a piece for the Washington Post in 2014 after Russia took Crimea in which he suggested that “the test is not absolute satisfaction but balanced dissatisfaction.”

This statement effectively sums up Kissinger’s famously realist view that high-stakes diplomacy must be infused with realpolitik (missing these days) and indeed may have guided him through his illustrious and often controversial career.

As a public intellectual, high-level practitioner and foreign policy influencer for over six decades, Kissinger is without peer. His hand was felt with varying degrees of consequence everywhere but it was his sustained involvement in the complex set of issues that informed and bedeviled the Middle East Peace Process that is the subject of Martin Indyk’s masterful and comprehensive Master of the Game: Henry Kissinger and the Art of Middle East Diplomacy.

To someone who has spent decades immersed in the day-to-day craft of Kissinger’s vocation with frequent forays into high-level diplomacy at the G7 level, reading Martin Indyk on Kissinger is essentially a master class by a master on a master.

Indyk, who, during my time at Canada’s embassy in Washington and afterward, was far and away the most insightful expert on the Middle East in town, whether as a practitioner (assistant secretary in the State Department, twice ambassador to Israel and special envoy for Middle East Peace) or as the affable senior guy with the distinctive Australian accent at the Brookings Institution who selflessly offered his views to Canadian diplomats.

What makes this thoroughly researched academic study of Kissinger’s influence on Middle East policy so interesting is the frequent juxtaposition and compelling comparisons of Kissinger’s efforts after the Yom Kippur war of 1973 with Indyk’s own travails in the region under presidents Clinton and Obama. It’s a little like the travel diary of one explorer discerning the footprints of an earlier nomad, and it reminds me of TS Eliot dedicating his great poem “The Waste Land” to Ezra Pound, in offering a lyrical study on post-war disillusionment (with a bit of an “I’m not worthy” vibe).

But it is all there and Indyk’s analysis is profound and eminently readable. He is informed by primary source materials, Kissinger memoranda and letters to an impressive array of regional and international actors, US government documents, telephone calls, secondary source analytical studies and, above all, personal interviews with Kissinger himself. His footnotes alone could be mined forever by academics in search of even greater detail than that already provided in the volume. World leaders, decision makers, celebrities all have their parts and more. Kissinger’s tireless “shuttle diplomacy” (the term was coined to describe his peripatetic approach to mediation) is detailed, as is his charming, cajoling, persuading and prevailing upon of the leaders of Egypt, Syria and Israel to relinquish territory in the pursuit of a viable, steady state of non-belligerence.

To someone who has spent decades immersed in the day-to-day craft of Kissinger’s vocation with frequent forays into high-level diplomacy at the G7 level, reading Martin Indyk on Kissinger is essentially a master class by a master on a master.

Indyk describes this approach to negotiation as the “skillful manipulation of the antagonisms of competing forces.” He does not however shy away from criticism: Kissinger should have done more to include Jordan’s King Hussein (Jordan is home to three million Palestinians — just one million fewer than the territory in dispute) to represent Palestinian interests in addition to Yasser Arafat’s Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) but with a variety of international spinning plates to keep aloft and Watergate consuming President Richard Nixon at home, Kissinger’s diplomacy really did become “the art of the possible”. Kissinger quickly overcame any doubts on Nixon’s part that his Jewish faith would become a real or perceived obstacle to his peacemaking.

To great effect, Indyk describes Kissinger’s establishment and effective use of front, back and side channels to exert both sustained influence and pressure on the key actors in the Middle East as well as on the Soviet Union. It seems at times during his period as national security advisor that his major antagonist was Secretary of State William Rogers who, with his department, was pursuing parallel but sometimes differing initiatives. While tension between the NSC and the State Department is not unusual, Indyk provides riveting examples of the behind-the-scenes internecine subterfuge exemplified in Kissinger’s exclusive channel to then Israeli ambassador to the US Yitzhak Rabin. With Kissinger as Rogers’ eventual successor at State, his former NSC deputy Brent Scowcroft was promoted, and, as expected, greater harmony ensued.

One gets the impression that Kissinger’s interactions with Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and Hafez al-Assad of Syria may have been easier. On the subject of the Soviets, Kissinger’s overriding objective in securing stability through the Geneva discussions in 1974 was to keep the USSR engaged but marginalized through a combination of talks, feints, bluster and threats. In assessing the US move to DEFCON 3 readiness in October of 1973 to pressure the Soviet Union to drop its proposal to send armed forces to Egypt, Indyk suggests quite credibly that it was Kissinger and not Nixon who took the decision.

Moves such as this underscore the notion that as both national security advisor and secretary of state, Kissinger possessed an extraordinary amount of power and influence, serving a beleaguered and addled president on the cusp of his Watergate resignation. Moreover, Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, came to rely completely on Kissinger’s judgment, given his own lack of familiarity with the issues and the fact that his secretary of state had been at the centre of the Middle East discussions in all phases for more than two years.

Indyk’s book is at once a marvellous, fast-paced rendition and analysis of international events and a paean to the vocation of diplomacy as practised by a master. It is historical but also written by a virtuoso practitioner who inserts reference points in US Middle East diplomacy in which he was deeply involved that give this comprehensive narrative a contemporary patina.

As a former career diplomat, two aspects of Kissinger’s story stand out for me. First, Indyk concludes that it was Kissinger’s relentless, deft and often brilliant personal diplomacy with all his interlocutors that built a framework for peace that lessened the existential threat against Israel, thereby providing the path for a far closer relationship with the US and its allies. This, of course, still holds. Second, Kissinger, despite the overwhelming power wielded by the US, developed peace mechanisms and approaches that were based in United Nations Security Council authority, in short, “the rules-based international order” to which all players, including the then-Soviet Union, agreed.

This framework — these well-established underpinnings which have served the conduct of international relations so well since 1945 — seems under great threat today. Perhaps Kissinger’s notion of “balanced dissatisfaction” will have to become our reference point. The question is how to achieve it.

Senator Peter Boehm, chair of the Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade, is a former ambassador and deputy minister who served as Canada’s sherpa for six G7 meetings.