Mea Culpa: The Conservative Leadership Process That I Helped Invent Needs an Overhaul

While the Conservative Party of Canada’s revolving door leadership syndrome is often blamed on internal divisions, the process by which leaders are chosen may be a contributing factor. Spectacle nostalgia won’t bring back the meatspace convention with its epic betrayals and riveting floor fights, but the current, one-member-one-vote selection process has serious flaws. Veteran Tory strategist and Earnscliffe Principal Geoff Norquay, who helped create the current system, has some suggestions.

Geoff Norquay

July 18, 2022

By September 10, the Conservative Party of Canada will have spent a total of 22 months of the past five years searching for a new leader. That’s what two failed leaders and the search for a third gives you, and it’s an awful lot of time for Canada’s alternative governing party to be on hold – handcuffed by interim management, unable to plan for the longer term and not fully engaged in holding the government to account.

The reason for the party’s long leadership contests is that they are based on a one-member-one-vote system accompanied by open recruitment, and that means the candidates need the time to sign up new members. Open recruitment has implications that are easy to criticize – that signing up new members is labour-intensive and expensive – so the party opens itself up to the possibility of under-the-table fundraising practices, bulk purchases of memberships on others’ behalf and faked memberships. As Globe and Mail columnist Andrew Coyne recently wrote, “Even if the candidates are not corrupt, the process is corrupting, producing very different candidates, and leaders, than would otherwise be the case.” The recent events that led to the dismissal of Patrick Brown from the current Conservative leadership race illustrate these risks.

Open recruitment also makes the leadership process vulnerable to outcome-swaying by special interests seeking to influence policy for as long as their chosen candidate is leader.

While leadership contests used to be managed in a completely different manner, through the delegated convention, it wasn’t always that way. For the first 50 years of Canada’s history, the leadership selection process was an informal and elite one, with both Conservative and Liberal leaders chosen through consultation involving the retiring leader, caucus members, senior party notables and fundraisers, and the governor general. By the 1920s, both parties had moved to leadership selection by a national convention, where each constituency association sent an equal number of representatives to elect the new leader. Within the former Progressive Conservative Party, this approach to choosing a new leader was in place until the mid-1990s.

After the crushing defeat of the Progressive Conservatives in the 1993 election, which saw them reduced to only two seats in the House, the new leader, Jean Charest, established a National Restructuring Committee to review the party’s operations, governance structures, policy development and leadership selection process. Full disclosure: as director of research for the committee, I wrote the analysis that led to the adoption of one-member one-vote leadership selection by the first national party in the country to do so: Mea culpa!

As the committee met with party members across the country, they complained that the process of selecting constituency delegates for leadership conventions was “divisive and destructive.” They argued that the scars left by these battles “are sometimes long-lasting or permanent, and hamper the reconciliation and reconstruction that must take place after the leadership is decided.”

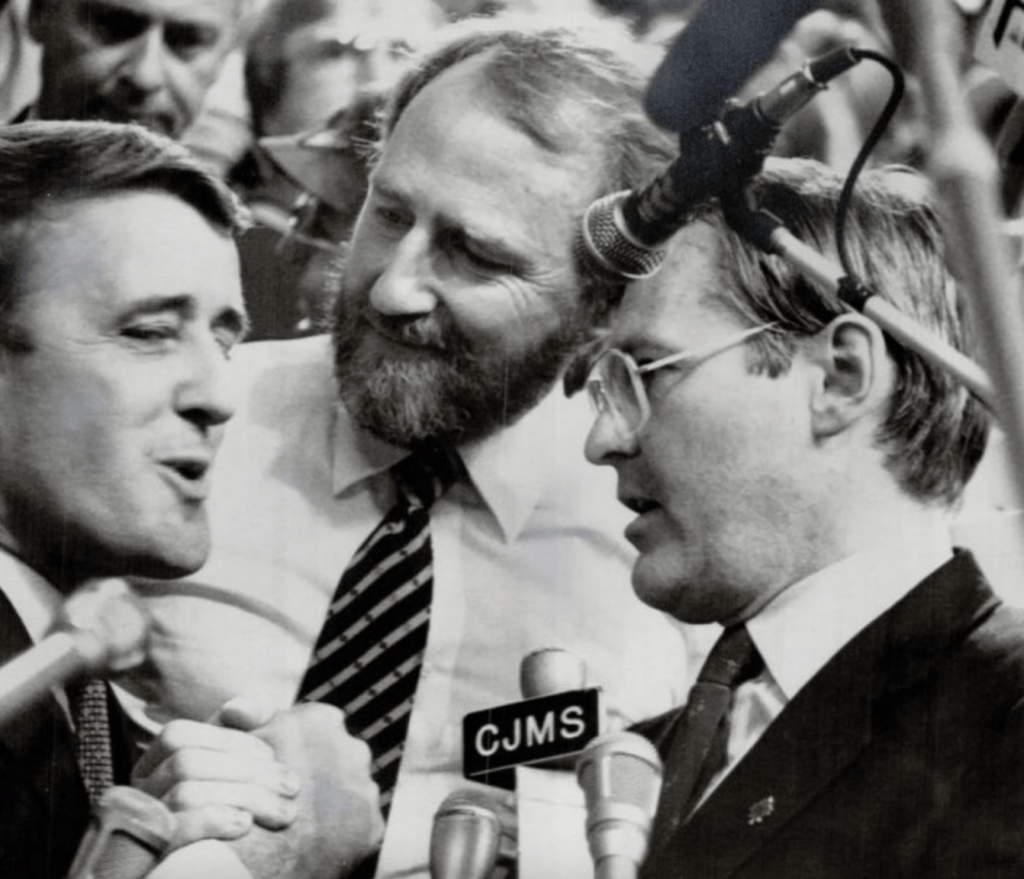

John Crosbie’s team brought a massive, tricked-out blimp to the 1983 convention that elected Brian Mulroney Progressive Conservative leader. What could possibly go wrong?

While some party members felt that the delegated convention “retains and supports the influence of the constituency association in the leadership selection process” thereby ensuring the future accountability of the leader, a clear majority wished to move to direct election by party members, seeing the new approach as “more democratic, open and accessible.” They also argued that with every member being able to cast a vote for leader, “there is a great incentive to recruit new members to the party.” A subsequent party convention sealed the deal, choosing the direct election leadership process, which was, in turn, adopted by the newly formed Conservative Party of Canada in 2004. All national parties in Canada have now adopted some form of member-based leadership selection.

On the face of it, direct election of the leader appeared to make a lot of sense. It was more inclusively democratic than the delegated convention, and it carried the added advantage of bringing “new blood” into the party through membership recruitment. When teamed with the 100 points per constituency system, which prevented constituencies with 2,000 members from overwhelming those with 200 members, it encouraged leadership candidates to recruit in the areas where the party was weakest. But here’s what one long-time Conservative says about that “advantage”: “Stacking riding associations has not gone out of fashion in the Conservative leadership selection process—it merely has morphed into flooding (by buying 10 or 20 memberships in some cases) virtually dormant riding associations to snatch up the 100 points.”

Open recruitment of new members and direct election has also displaced the most engaged local party activists and stalwarts who showed up through thick and thin, recruiting and coaching the next candidate, fundraising, running the campaign office and knocking on doors at election time. Today, who knows if the thousands of new members recruited to support a specific leadership candidate will stick around to contribute locally for the long haul?

Despite the imperfections of the delegated convention, political parties lost a lot with its demise. Local delegates to a leadership convention were deprived of the opportunity to meet as a party, bond with fellow members and participate in a national spectacle. As historian John Courtney has written, “Competition is made for television, whether in politics or sports.” A leadership convention that lasted several days presented a huge opportunity for the party to present itself to the people of the country on national television. Over successive ballots, the hand-to-hand combat among the contenders was visible and transparent, as were the dynamics and excitement of coalition building on the convention floor, in real time.

It all made for some memorable moments:

- At the 1968 Liberal convention that chose Pierre Trudeau as leader, the TV cameras captured health minister Judy LaMarsh desperately trying to convince Paul Hellyer to withdraw in favour of Robert Winters to “stop that bastard Trudeau.”

- John Crosbie’s team brought a massive, tricked-out blimp to the 1983 convention that elected Brian Mulroney Progressive Conservative leader. What could possibly go wrong? Well, the blimp became uncontrollable and went rogue, cruising among the 5,000 delegates, crashing into press boxes and TV cameras. It was amazing television.

- At the NDP leadership convention in 1989, contender Simon de Jong dithered and fumed over whom to support once he was eliminated as he tried to find his mother to get her advice: “Oh Mummy, Mummy, what should I do? Where should I go?”

Contrast all that with what happens today in one-member one-vote leadership contests. The dealmaking for down-ballot support is all negotiated in advance among the contestants and in secret. A candidate can make the best speech of his or her life, but it doesn’t matter, because the votes have all been cast, sent and tabulated weeks before. In a leadership with ranked preferential ballots, the suspense of successive votes is lost and the only way a party can sustain the viability of the TV event unveiling the new leader is to delay announcing the results of each ballot.

It’s a good bet that the delegated convention is not coming back: reforms that increase participation and broaden democracy are rarely called back. But how could the Conservative model be improved, beginning with how could it be shortened?

The process for the replacement of Boris Johnson as leader of the British Conservative Party provides some useful ideas. Here’s how that process is unfolding:

- Johnson resigned as leader on July 7

- On nomination day, which was July 12, eight candidates declared, having gained the support of at least 20 MPs to get to the first ballot

- Between July 13 and July 21, successive votes by the Conservative caucus a few days apart reduced the number of candidates one by one, until only two remained.

- More than 200,000 individual members of the party, who have been paid up members for three months, could then choose the winner by postal ballot, with the outcome announced on September 5.

Several points about this process are striking. First, in the initial stage of the UK approach, the British Conservative caucus plays a much more important role than its Canadian counterpart in leadership selection; the British system ensures at least a minimum level of support among caucus members. Second, the round-by-round caucus votes to deplete the number of contenders simplifies the process for the party voters and eliminates the need for a transferable preferential ballot. Third, party memberships are frozen as of three months before the vote, so the need to recruit new members of the party simply does not exist. Fourth, the entire British process from start to finish was to be completed in two months, and at a fraction of the cost and significantly less wear and tear on the contestants and the party than the Canadian approach. Perhaps most importantly, the party will not be reduced to that status of a bystander for six months as it is in Canada.

As Canada’s Conservative Party looks to future leadership elections, this is a model they might wish to consider.

Contributing Writer Geoff Norquay was lead adviser on social policy in the Prime Minister’s Office for Brian Mulroney and director of communications under Stephen Harper in the Opposition Leader’s Office from 2004-06. He is a Principal at Earnscliffe Strategies in Ottawa.