Mulroney and Human Rights: When Power Met Principle

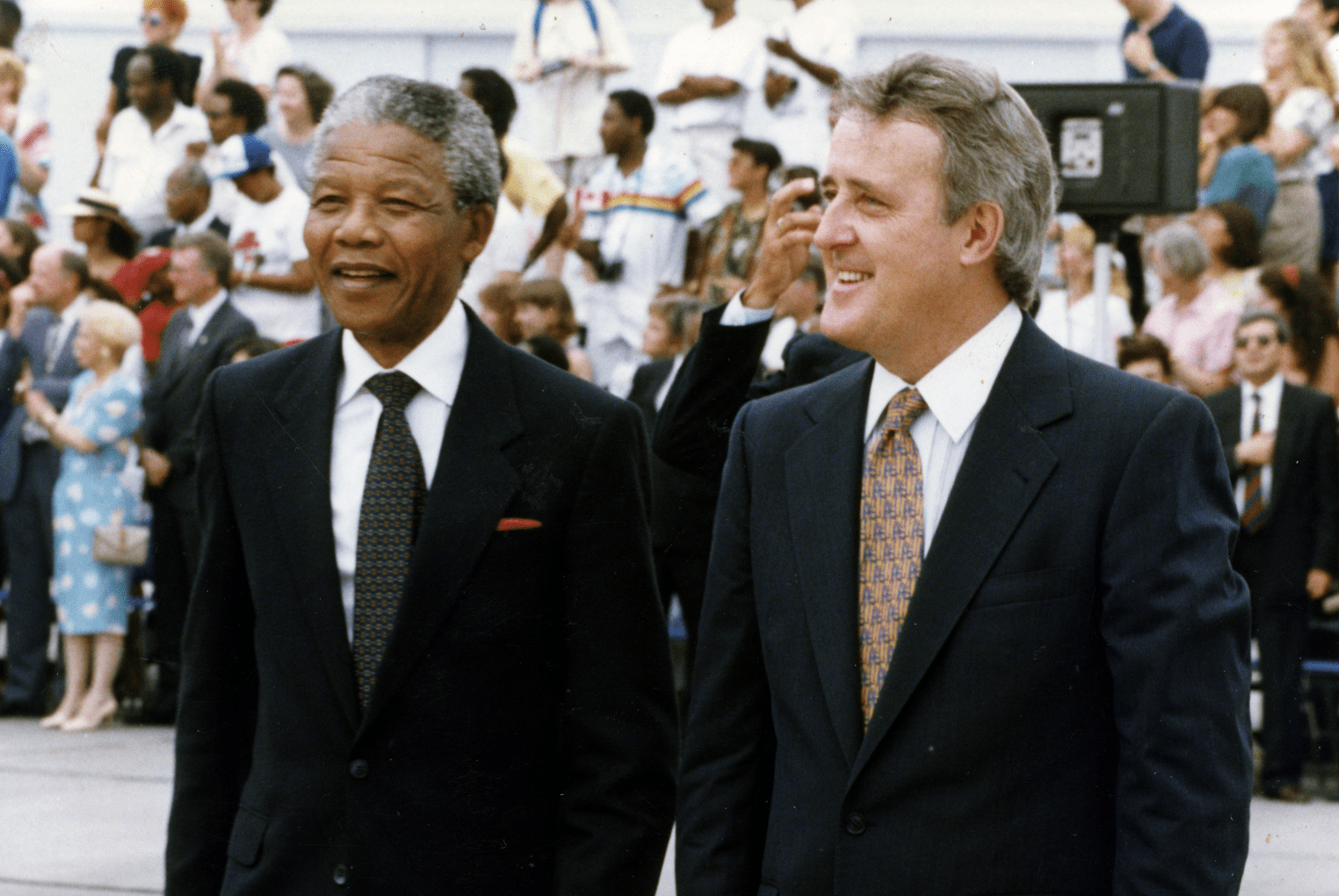

Nelson Mandela arrives in Ottawa, June, 1990/Bill McCarthy

Nelson Mandela arrives in Ottawa, June, 1990/Bill McCarthy

By Lisa Van Dusen

March 8, 2024

There was an early moment in my experience as a press assistant for Brian Mulroney that crystallized both why I was where I was, and why he would quite likely be prime minister.

It happened in the House of Commons on October 6th, 1983. Mulroney was threading the needle created by a political piège set by the Trudeau government to force his hand on minority language rights at a time when the Conservative caucus was still, to put it politely, not quite unanimous on the question.

It was just four months after Mulroney had won the leadership of a Conservative Party he was trying to mainstream toward broader electability and four months before Pierre Trudeau’s walk in the snow triggered the federal election that would determine the success or failure of that experiment. (Mulroney won the largest majority in Canadian history).

The choice Mulroney made that day seemed to reflect the sum of lessons learned in courtrooms as a lawyer, the hard way as a political strategist and from personal experience as a kid with an Irish name growing up in small-town Quebec. Instead of responding to a tactical stunt by doubling down on tactics, he responded with principle.

Or, as longtime La Presse editor and columnist and later senator André Pratte put it in a 2018 Toronto Star column: “Mulroney did not fall into the trap. Quite the contrary, he rose to the occasion. He succeeded in convincing his caucus to unanimously support the Liberal motion. And, before the historic vote, Mulroney delivered a remarkable speech: ‘Our collective evolution has determined that two peoples speaking English and French were united in a great national adventure. This unique situation has given birth to our Canadian citizenship…’”

I was sitting in the gallery that day as a 21-year-old former Press Gallery reporter and recently recruited press aide in part — as with other bilingual anglo journos who gravitated into his orbit despite not being Conservatives — because of this issue (I went to work for him because of his beliefs, I moved leftward as I got older because of mine). And the quotation that got me was the one cited by Mulroney from Justice Learned Hand (considered the greatest American jurist never to sit on the US Supreme Court), from his 1944 “Spirit of Liberty” speech: “The spirit of liberty remembers that not even a sparrow falls to earth unheeded.”

That notion, that the rights of one impact equally the rights of all, is echoed in Martin Luther King’s assertions that “injustice anywhere is a threat to injustice everywhere,” and that we are all “caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

It’s tempting to displace these principles from our own experience as a means of distancing ourselves from their existential value to people whose rights have been obliterated or are in the course of being violated. But that denial reflex only underscores their indispensability to human progress. They mattered then, and they matter even more now.

They mattered to King and the non-violent Civil Rights warriors; they mattered to the political prisoners of the Soviet Union Mulroney helped dismantle; they matter to the Palestinians still waging a mortal battle for their basic human rights; they matter to Jews in Israel and worldwide still fighting antisemitism; they mattered to Nelson Mandela when he was wondering whether he would die in prison, and they mattered to Alexei Navalny when he was wondering the same thing.

In the 1980s, the Nelson Mandela of public perception was not the eloquent, benevolent statesman Nelson Mandela the world was able to know once he was free. There were two images of him in wide circulation, they were both a quarter-century out of date, and one of them was a grainy mugshot. South Africa’s apartheid regime was so paranoid about Mandela’s personal power that it was illegal to possess or publish an image of him that could update that limited, outdated and politically convenient perception.

The fact that Mandela did not die in prison fundamentally unknown to the world 34 years ago and Navalny died in prison fully known to the world last month attests to the horrible backsliding in human rights wrought by the war on democracy.

At a moment in history when human rights are being degraded globally by state and non-state wireless surveillance and hacking, by judicial corruption, by overt and covert disenfranchisement, and by the reality-distorting, chaos-fomenting, misdirectional, misleading and misrepresentational weapons of performative propaganda and narrative warfare, Mulroney’s record on the inviolability of these basic, universal principles of human rights is worth recalling.

The fact that Mandela did not die in prison fundamentally unknown to the world 34 years ago and Navalny died in prison fully known to the world last month attests to the horrible backsliding in human rights wrought by the war on democracy.

In July, 1986, when the Canadian prime minister — not infrequently criticized for being a so-called lapdog to Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher — was pressuring Thatcher to mobilize the Commonwealth to impose sanctions on South Africa’s pathocratically racist regime, The Washington Post’s Herb Denton wrote the following once Thatcher was wheel’s-up after their Montreal bilateral:

“The Canadian prime minister, waving a finger for emphasis, spoke with strong emotion. ‘It’s all about dealing with a regime that is rooted in evil, when an entire generation of people have been suppressed, deprived of their fundamental rights, their liberty and dignity as human beings. It’s a regime constructed on the concept that people are fundamentally unequal. It is unacceptable to civilized governments and civilized societies. It ought to be unacceptable to all of us of the Commonwealth and all prime ministers.”

In his address to the United Nations General Assembly the year before, Mulroney had been scathing toward Pretoria. “Only one country has established colour as the hallmark of systemic inequality and repression,” he told the UNGA. “Only South Africa determines the fundamental human rights of individuals and groups within its society by this heinous method of classification.”

“You have to have been in the General Assembly to appreciate what happened when those words were uttered,” Former UN ambassador Stephen Lewis recalled in 2014. “I was at the UN for four glorious years. I had never seen anything like it before, and I never saw anything like it afterwards. It was an extraordinary moment.”

These days, we’ve been conditioned by propaganda fog, creeping self-censorship and misplaced moral equivalence to somehow accept that good and bad have become decoupled from character, as have popularity and success; two commodities now so easy to misrepresent that a US presidential election between a twice-impeached, coup plotting clown facing 91 felony charges and a rational, face-value, real-life president with the best economic record in the G7 is playing out as a nail-biter.

When Brian Mulroney put his friendship with Margaret Thatcher on the line, his relationship with a more amenable but circumscribed Queen Elizabeth on the line, and his leadership in the Commonwealth on the line for one inmate halfway around the world, he didn’t do it for popularity.

It wasn’t until 1988 that the Free Mandela concert marking that inmate’s 70th birthday raised the outcry to such a globally galvanizing pitch that Fox news was accused of censoring the broadcast from Wembley stadium to contain it. It was called “Freedomfest – Nelson Mandela’s 70th Birthday Celebration” (Anyone for a “FreedomFest II — Liberating Democracy”?) and it mobilized a critical mass of momentum toward sanity that became so unstoppable, change was suddenly, irrevocably accelerated by inevitability.

But Mulroney’s intervention had been crucial because he was a white, Western, Conservative (much more small-L liberal than the label connotes today) G7, NATO and Commonwealth leader who could have kept his mouth shut and had a much easier time of it — spending all that political, diplomatic and intellectual capital on more electorally advantageous international causes, or just thankless-tasking his way through endless domestic constitutional wrangling. His moral leadership on Mandela and apartheid mattered precisely because we’re not used to seeing world leaders spend and risk their power so doggedly just to do the right thing.

Since then, politics have changed and human rights have changed. Today, tyrants, bullies, dictators and despots — elected and unelected — can use technology to remotely obliterate privacy and freedom. They use narrative and hybrid warfare to manipulate and misrepresent events to their advantage and use propaganda to elevate themselves and systematically degrade opponents. In new world order/anti-democracy circles, getting away with covert human rights violations in broad daylight in ostensibly functioning democracies is the new dekulakization.

In this atmosphere, people in politics, in government, in journalism, in the judiciary, are constantly being compelled to choose between power and principle, and when that goes on long enough, you get the industrialized absurdity now showing on any screen near you.

Whatever Brian Mulroney thought about today’s rights recession, there was a time when he stood up and proved that power and principle could not only coexist, they could mend a tear in the single garment of destiny.

Policy Magazine Editor and Publisher Lisa Van Dusen has served as a senior writer at Maclean’s, Washington bureau chief for Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington. She was also director of media relations for McGill University.